6 Avoiding Trial

6.1 Arbitration

Kalinauskas v. Wong

JOHNSTON, M.J.

This matter was submitted to the undersigned Magistrate Judge on a Motion for a Protective Order filed by defendant Desert Palace, Inc., doing business as Caesars Palace Hotel & Casino (Caesars). […]

The plaintiff, Ms. Lin T. Kalinauskas (Kalinauskas), a former employee of Caesars, has sued Caesars for sexual discrimination in the instant case. As part of discovery Kalinauskas seeks to depose Donna R. Thomas, a former Caesars employee who filed a sexual harassment suit against Caesars last year. Ms. Thomas’s suit settled without trial pursuant to a confidential settlement agreement[,] which the court sealed upon the stipulated agreement of the parties.

This court has examined, in camera, sealed materials relating to Ms. Thomas’s case and settlement. The in camera submission included: Stipulation for & Order for Dismissal, Protective Order and Confidentiality Order, Stipulation for Protective Order and Confidentiality Order, and Settlement Agreement. [The Stipulation for a Protective Order provided] that the plaintiff “shall not discuss any aspect of plaintiff’s employment at Caesars other than to state the dates of her employment and her job title.” Identical language appears in the Protective Order and Confidentiality Order. […]

Discussion

In general, the scope of discovery is very broad. “Parties may obtain discovery regarding any [unprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense]” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(1) (emphasis added). The primary goal of the court and discovery is “to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 1.

The public interest favors judicial policies which promote the completion of litigation. Public interest also seeks to protect the finality of prior suits and the secrecy of settlements when desired by the settling parties. However, the courts also serve society by providing a public forum for issues of general concern. The case at bar presents a direct conflict between these crucial public and private interests.

To allow full discovery into all aspects of Ms. Thomas’s case could discourage similar settlements. Confidential settlements benefit society and the parties involved by resolving disputes relatively quickly, with slight judicial intervention, and presumably result in greater satisfaction to the parties. Sound judicial policy fosters and protects this form of alternative dispute resolution. See, e.g., Fed. R. Evid. 408 which protects compromises and offers to compromise by rendering them inadmissible to prove liability. The secrecy of a settlement agreement and the contractual rights of the parties thereunder deserve court protection.

On the other hand, to prevent any discovery into Ms. Thomas’s case based upon the settlement agreement results in disturbing consequences. First, as pointed out by Kalinauskas, preventing the deposition of Ms. Thomas would condone the practice of “buy[ing] the silence of a witness with a settlement agreement.” This court harbors little doubt that preventing the dissemination of the underlying facts which prompted Ms. Thomas to file suit is in Caesars’s interest, and formed an important part of the agreement to Caesars. Caesars avers that without the confidentiality order the Thomas case would not have settled. Yet despite this freedom to contract, the courts must carefully police the circumstances under which litigants seek to protect their interests while concealing legitimate areas of public concern. This concern grows more pressing as additional individuals are harmed by identical or similar action.

Second, the deposition of Ms. Thomas is likely to lead to relevant evidence. Preventing the deposition of Ms. Thomas or the discovery of documents created in her case could lead to wasteful efforts to generate discovery already in existence. […]

Caesars[’s] motion for a protective order preventing the deposition of Ms. Thomas rests entirely upon the confidential settlement agreement. Caesars … maintains that it should be able to rely upon the confidentiality order to protect against [disclosure to] third parties, unless extraordinary circumstances or compelling need justifies some breach of secrecy. […]

[Caesars’s] argument that Kalinauskas must show a compelling need to obtain discovery applies to discovery of the specific terms of the settlement agreement (i.e., the amount and conditions of the agreement), not [to] factual information surrounding Thomas’s case. Caesars should not be able to conceal basic facts of concern to Kalinauskas in her case, and of legitimate public concern, regarding employment at its place of business.

Accordingly, keeping in mind the liberal nature of discovery, this court will allow the deposition of Ms. Thomas. […] The deposition of Ms. Thomas and any further discovery into the Thomas case must not, however, disclose any substantive terms of the Caesars-Thomas settlement agreement. Naturally, Ms. Thomas may answer questions regarding her employment at Caesars and any knowledge of sexual harassment.

Although the terms of the confidential settlement agreement impose penalties upon Ms. Thomas for discussing her past employment at Caesars, those penalties shall not apply to the disclosure of information for discovery purposes in furtherance of Kalinauskas’s case. Indeed, the settlement agreement itself makes exception for court ordered release of information.

While settlement is an important objective, an overzealous quest for alternative dispute resolution can distort the proper role of the court. Furthermore, settlement agreements which suppress evidence violate the greater public policy. […]

Based on the foregoing […] IT IS HEREBY ORDERED […] that the Defendant’s Motion for Protective Order is granted to the extent that during the deposition of Ms. Donna R. Thomas, no information regarding the settlement agreement itself shall come forth [and] that the Defendant’s Motion for Protective Order is denied as to all other requests. […]

Notes & Questions

Why did Kalinauskas want to depose Ms. Thomas?

Why didn’t Caesars want that to happen?

What was Caesars’ argument?

Why do you think the settlement between Caesars and Ms. Thomas was confidential?

What was the Court’s holding?

Ferguson v. Countrywide Credit Industries, Inc.

PREGERSON, J.

Misty Ferguson filed a complaint against Countrywide Credit Industries, Inc. and her supervisor, Leo DeLeon, alleging causes of action under federal and state law for sexual harassment, retaliation, and hostile work environment. Countrywide filed a petition for an order compelling arbitration of Ferguson’s claims. The district court denied Countrywide’s petition on the grounds that Countrywide’s arbitration agreement is unenforceable based on the doctrine of unconscionability.

I. Factual and Procedural History

When Ferguson was hired she was required to sign Countrywide’s Conditions of Employment, which states in relevant part: “I understand that in order to work at Countrywide I must execute an arbitration agreement.”

The district court denied Countrywide’s petition to compel arbitration. It ruled that the arbitration agreement is unenforceable because it is unconscionable under Armendariz v. Foundation Health Psychcare Services, Inc., 24 Cal. 4th 83 (2000).

II. Unconscionability

The FAA compels judicial enforcement of a wide range of written arbitration agreements. Section 2 of the FAA provides, in relevant part, that arbitration agreements “shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds that exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.” 9 U.S.C. § 2. In determining the validity of an agreement to arbitrate, federal courts “should apply ordinary state-law principles that govern the formation of contracts.” “Thus, generally applicable defenses, such as unconscionability, may be applied to invalidate arbitration agreements without contravening the FAA.” California courts may invalidate an arbitration clause under the doctrine of unconscionability. This doctrine, codified by the California Legislature in California Civil Code 1670.5(a), provides:

if the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made, the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to avoid any unconscionable result.

This statute, however, does not define unconscionability. Instead, we look to the California Supreme Court’s decision in Armendariz, which provides the definitive pronouncement of California law on unconscionability to be applied to mandatory arbitration agreements, such as the one at issue in this case. In order to render a contract unenforceable under the doctrine of unconscionability, there must be both a procedural and substantive element of unconscionability. These two elements, however, need not both be present in the same degree. Thus, for example, the more substantively oppressive the contract term, the less evidence of procedural unconscionability is required to come to the conclusion that the term is unenforceable.

1. Procedural Unconscionability

Procedural unconscionability concerns the manner in which the contract was negotiated and the circumstances of the parties at that time. A determination of whether a contract is procedurally unconscionable focuses on two factors: oppression and surprise. Oppression arises from an inequality of bargaining power which results in no real negotiation and an absence of meaningful choice. Surprise involves the extent to which the supposedly agreed-upon terms of the bargain are hidden in the prolix printed form drafted by the party seeking to enforce the disputed terms.

In Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Adams, 279 F.3d 889, 892 (9th Cir. 2002), we held that the arbitration agreement at issue satisfied the elements of procedural unconscionability under California law. We found the agreement to be procedurally unconscionable because Circuit City, which possesses considerably more bargaining power than nearly all of its employees or applicants, drafted the contract and uses it as its standard arbitration agreement for all of its new employees. The agreement is a prerequisite to employment, and job applicants are not permitted to modify the agreement’s terms—they must take the contract or leave it.

2. Substantive Unconscionability

Substantive unconscionability focuses on the terms of the agreement and whether those terms are so one-sided as to shock the conscience. Just before oral argument was heard in this case, the California Court of Appeal held in another case that Countrywide’s arbitration agreement was unconscionable. See Mercuro v. Superior Court, 96 Cal. App. 4th 167 (2002).

a. One-Sided Coverage of Arbitration Agreement

Countrywide’s arbitration agreement specifically covers claims for breach of express or implied contracts or covenants, tort claims, claims of discrimination or harassment based on race, sex, age, or disability, and claims for violation of any federal, state, or other governmental constitution, statute, ordinance, regulation, or public policy. On the other hand, the arbitration agreement specifically excludes claims for workers’ compensation or unemployment compensation benefits, injunctive and/ or other equitable relief for intellectual property violations, unfair competition and/or the use and/or unauthorized disclosure of trade secrets or confidential information. We adopt the California appellate court’s holding in Mercuro, that Countrywide’s arbitration agreement was unfairly one-sided and, therefore, substantively unconscionable because the agreement “compels arbitration of the claims employees are most likely to bring against Countrywide … [but] exempts from arbitration the claims Countrywide is most likely to bring against its employees.”

[…]

b. Arbitration Fees

In Armendariz, the California Supreme Court held that:

when an employer imposes mandatory arbitration as a condition of employment, the arbitration agreement or arbitration process cannot generally require the employee to bear any type of expense that the employee would not be required to bear if he or she were free to bring the action in court. This rule will ensure that employees bringing [discrimination] claims will not be deterred by costs greater than the usual costs incurred during litigation, costs that are essentially imposed on an employee by the employer.

Countrywide’s arbitration agreement has a provision that requires the employee to “pay to NAF [National Arbitration Forum] its filing fee up to a maximum of $125.00 when the Claim is filed. The Company shall pay for the first hearing day. All other arbitration costs shall be shared equally by the Company and the Employee.” Countrywide argues that this provision is not so one-sided as to “shock the conscience” and, therefore, is enforceable.

However, Armendariz holds that a fee provision is unenforceable when the employee bears any expense beyond the usual costs associated with bringing an action in court. NAF imposes multiple fees which would bring the cost of arbitration for Ferguson into the thousands of dollars.

Because the only valid fee provision is one in which an employee is not required to bear any expense beyond what would be required to bring the action in court, we affirm the district court’s conclusion that “the original fee provision … appears clearly to violate the Armendariz standard.”

c. One-Sided Discovery Provision

Ferguson also argues that the discovery provision in the arbitration agreement is one-sided and, therefore, unconscionable. The discovery provision states that “a deposition of a corporate representative shall be limited to no more than four designated subjects,” but does not impose a similar limitation on depositions of employees. Ferguson also notes that the arbitration agreement sets mutual limitations (e.g., no more than three depositions) and mutual advantages (e.g., unlimited expert witnesses) which favor Countrywide because it is in a superior position to gather information regarding its business practices and employees’ conduct, and has greater access to funds to pay for expensive expert witnesses.

Ferguson urges this court to affirm the district court’s ruling that the discovery provision is unconscionable on the ground that the limitations and mutual advantages on discovery are unfairly one-sided and have no commercial justification other than “maximizing employer advantage,” which is an improper basis for such differences under Armendariz. Countrywide argues to the contrary that the arbitration agreement provides for ample discovery by employees.

In Armendariz, the California Supreme Court held that employees are “at least entitled to discovery sufficient to adequately arbitrate their statutory claims, including access to essential documents and witnesses.” Adequate discovery, however, does not mean unfettered discovery. As Armendariz recognized, an arbitration agreement might specify “something less than the full panoply of discovery provided in the California Code of Civil Procedure.”

In Mercuro, the California Court of Appeals applied the parameters set forth in Armendariz to Countrywide’s discovery provisions. It concluded that “without evidence showing how these discovery provisions are applied in practice, we are not prepared to say they would not necessarily prevent Mercuro from vindicating his statutory rights.” Mercuro relied heavily on the ability of the arbitrator to extend the discovery limits for “good cause.” In fact, Mercuro ultimately left it up to the arbitrator to balance the need for simplicity in arbitration with the discovery necessary for a party to vindicate her claims. Following the Court in Mercuro, we too find that Countrywide’s discovery provisions may afford Ferguson adequate discovery to vindicate her claims.

Nevertheless, we recognize an insidious pattern in Countrywide’s arbitration agreement. Not only do these discovery provisions appear to favor Countrywide at the expense of its employees, but the entire agreement seems drawn to provide Countrywide with undue advantages should an employment-related dispute arise. Aside from merely availing itself of the cost-saving benefits of arbitration, Countrywide has sought to advantage itself substantively by tilting the playing field.

While many of its arbitration provisions appear equally applicable to both parties, these provisions may work to curtail the employee’s ability to substantiate any claim against the employer. We follow Mercuro in holding that the discovery provisions alone are not unconscionable, but in the context of an arbitration agreement which unduly favors Countrywide at every turn, we find that their inclusion reaffirms our belief that the arbitration agreement as a whole is substantively unconscionable.

Conclusion

The district court’s denial of Countrywide’s petition to compel arbitration on the ground that Countrywide’s arbitration agreement is unenforceable under the doctrine of unconscionability is AFFIRMED.

Notes & Questions

What kind of motion did Countrywide file seeking to force Ferguson to arbitrate her claims? What legal authority did they rely for doing so?

What are the two aspects (and their subparts) of the law of unconscionability under California law? Is it enough for either one to be satisfied, or must both be met?

Note that Ferguson is an outlier case. Other cases considering whether to enforce similar arbitration clauses have come out the other way. See, e.g., Carter v. Countrywide Credit Industries, Inc., 362 F.3d 294 (5th Cir. 2004).

Epic Systems v. Lewis

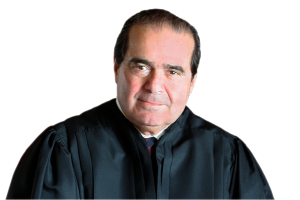

GORSUCH, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

Should employees and employers be allowed to agree that any disputes between them will be resolved through one-on-one arbitration? Or should employees always be permitted to bring their claims in class or collective actions, no matter what they agreed with their employers?

As a matter of policy these questions are surely debatable. But as a matter of law the answer is clear. In the Federal Arbitration Act, Congress has instructed federal courts to enforce arbitration agreements according to their terms—including terms providing for individualized proceedings. Nor can we agree with the employees’ suggestion that the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) offers a conflicting command. It is this Court’s duty to interpret Congress’s statutes as a harmonious whole rather than at war with one another. And abiding that duty here leads to an unmistakable conclusion. The NLRA secures to employees rights to organize unions and bargain collectively, but it says nothing about how judges and arbitrators must try legal disputes that leave the workplace and enter the courtroom or arbitral forum. This Court has never read a right to class actions into the NLRA—and for three quarters of a century neither did the National Labor Relations Board. Far from conflicting, the Arbitration Act and the NLRA have long enjoyed separate spheres of influence and neither permits this Court to declare the parties’ agreements unlawful.

I

The three cases before us differ in detail but not in substance. Take Ernst & Young LLP v. Morris. There Ernst & Young and one of its junior accountants, Stephen Morris, entered into an agreement providing that they would arbitrate any disputes that might arise between them. The agreement stated that the employee could choose the arbitration provider and that the arbitrator could “grant any relief that could be granted by … a court” in the relevant jurisdiction. The agreement also specified individualized arbitration, with claims “pertaining to different [e]mployees [to] be heard in separate proceedings.”

After his employment ended, and despite having agreed to arbitrate claims against the firm, Mr. Morris sued Ernst & Young in federal court. He alleged that the firm had misclassified its junior accountants as professional employees and violated the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and California law by paying them salaries without overtime pay. Although the arbitration agreement provided for individualized proceedings, Mr. Morris sought to litigate the federal claim on behalf of a nationwide class under the FLSA’s collective action provision, 29 U.S.C. § 216(b). He sought to pursue the state law claim as a class action under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23.

Ernst & Young replied with a motion to compel arbitration. The district court granted the request, but the Ninth Circuit reversed this judgment. The Ninth Circuit recognized that the Arbitration Act generally requires courts to enforce arbitration agreements as written. But the court reasoned that the statute’s “saving clause,” see 9 U.S.C. § 2, removes this obligation if an arbitration agreement violates some other federal law. And the court concluded that an agreement requiring individualized arbitration proceedings violates the NLRA by barring employees from engaging in the “concerted activit[y],” of pursuing claims as a class or collective action. […]

Although the Arbitration Act and the NLRA have long coexisted—they date from 1925 and 1935, respectively—the suggestion they might conflict is something quite new. Until a couple of years ago, courts more or less agreed that arbitration agreements like those before us must be enforced according to their terms. […]

II

We begin with the Arbitration Act and the question of its saving clause.

Congress adopted the Arbitration Act in 1925 in response to a perception that courts were unduly hostile to arbitration. No doubt there was much to that perception. Before 1925, English and American common law courts routinely refused to enforce agreements to arbitrate disputes. But in Congress’s judgment arbitration had more to offer than courts recognized—not least the promise of quicker, more informal, and often cheaper resolutions for everyone involved. So Congress directed courts to abandon their hostility and instead treat arbitration agreements as “valid, irrevocable, and enforceable.” 9 U.S.C. § 2. The Act, this Court has said, establishes “a liberal federal policy favoring arbitration agreements.”

Not only did Congress require courts to respect and enforce agreements to arbitrate; it also specifically directed them to respect and enforce the parties’ chosen arbitration procedures.

On first blush, these emphatic directions would seem to resolve any argument under the Arbitration Act. The parties before us contracted for arbitration. They proceeded to specify the rules that would govern their arbitrations, indicating their intention to use individualized rather than class or collective action procedures. And this much the Arbitration Act seems to protect pretty absolutely. See AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011). You might wonder if the balance Congress struck in 1925 between arbitration and litigation should be revisited in light of more contemporary developments. You might even ask if the Act was good policy when enacted. But all the same you might find it difficult to see how to avoid the statute’s application.

Still, the employees suggest the Arbitration Act’s saving clause creates an exception for cases like theirs. By its terms, the saving clause allows courts to refuse to enforce arbitration agreements “upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.” § 2. That provision applies here, the employees tell us, because the NLRA renders their particular class and collective action waivers illegal. In their view, illegality under the NLRA is a “ground” that “exists at law … for the revocation” of their arbitration agreements, at least to the extent those agreements prohibit class or collective action proceedings.

The problem with this line of argument is fundamental. […]

[The clause] can’t [apply] because the saving clause recognizes only defenses that apply to “any” contract. In this way the clause establishes a sort of “equal-treatment” rule for arbitration contracts. The clause “permits agreements to arbitrate to be invalidated by ‘generally applicable contract defenses, such as fraud, duress, or unconscionability.’” Concepcion. At the same time, the clause offers no refuge for “defenses that apply only to arbitration or that derive their meaning from the fact that an agreement to arbitrate is at issue.” Under our precedent, this means the saving clause does not save defenses that target arbitration either by name or by more subtle methods, such as by “interfer[ing] with fundamental attributes of arbitration.”

This is where the employees’ argument stumbles. They don’t suggest that their arbitration agreements were extracted, say, by an act of fraud or duress or in some other unconscionable way that would render any contract unenforceable. Instead, they object to their agreements precisely because they require individualized arbitration proceedings instead of class or collective ones. And by attacking (only) the individualized nature of the arbitration proceedings, the employees’ argument seeks to interfere with one of arbitration’s fundamental attributes.

We know this much because of Concepcion. There this Court faced a state law defense that prohibited as unconscionable class action waivers in consumer contracts. The Court readily acknowledged that the defense formally applied in both the litigation and the arbitration context. But, the Court held, the defense failed to qualify for protection under the saving clause because it interfered with a fundamental attribute of arbitration all the same. It did so by effectively permitting any party in arbitration to demand classwide proceedings despite the traditionally individualized and informal nature of arbitration. This “fundamental” change to the traditional arbitration process, the Court said, would “sacrific[e] the principal advantage of arbitration—its informality—and mak[e] the process slower, more costly, and more likely to generate procedural morass than final judgment.” […]

Of course, Concepcion has its limits. The Court recognized that parties remain free to alter arbitration procedures to suit their tastes, and in recent years some parties have sometimes chosen to arbitrate on a classwide basis. But Concepcion’s essential insight remains: courts may not allow a contract defense to reshape traditional individualized arbitration by mandating classwide arbitration procedures without the parties’ consent. Just as judicial antagonism toward arbitration before the Arbitration Act’s enactment “manifested itself in a great variety of devices and formulas declaring arbitration against public policy,” Concepcion teaches that we must be alert to new devices and formulas that would achieve much the same result today. And a rule seeking to declare individualized arbitration proceedings off limits is, the Court held, just such a device. […]

Illegality[, as the term is used in the NLRA], like unconscionability, may be a traditional, generally applicable contract defense in many cases, including arbitration cases. But an argument that a contract is unenforceable just because it requires bilateral arbitration is a different creature. A defense of that kind, Concepcion tells us, is one that impermissibly disfavors arbitration whether it sounds in illegality or unconscionability. The law of precedent teaches that like cases should generally be treated alike, and appropriate respect for that principle means the Arbitration Act’s saving clause can no more save the defense at issue in these cases than it did the defense at issue in Concepcion. At the end of our encounter with the Arbitration Act, then, it appears just as it did at the beginning: a congressional command requiring us to enforce, not override, the terms of the arbitration agreements before us.

[…]

IV

The dissent sees things a little bit differently. In its view, today’s decision ushers us back to the Lochner era when this Court regularly overrode legislative policy judgments. The dissent even suggests we have resurrected the long-dead “yellow dog” contract. But like most apocalyptic warnings, this one proves a false alarm. […]

Our decision does nothing to override Congress’s policy judgments. As the dissent recognizes, the legislative policy embodied in the NLRA is aimed at “safeguard[ing], first and foremost, workers’ rights to join unions and to engage in collective bargaining.” Those rights stand every bit as strong today as they did yesterday. And rather than revive “yellow dog” contracts against union organizing that the NLRA outlawed back in 1935, today’s decision merely declines to read into the NLRA a novel right to class action procedures that the Board’s own general counsel disclaimed as recently as 2010. […]

* * *

The policy may be debatable but the law is clear: Congress has instructed that arbitration agreements like those before us must be enforced as written. While Congress is of course always free to amend this judgment, we see nothing suggesting it did so in the NLRA—much less that it manifested a clear intention to displace the Arbitration Act. Because we can easily read Congress’s statutes to work in harmony, that is where our duty lies. […]

So ordered.

GINSBURG, J., with whom BREYER, J., SOTOMAYOR, J., and KAGAN, J., join, dissenting.

The employees in these cases complain that their employers have underpaid them in violation of the wage and hours prescriptions of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA) and analogous state laws. Individually, their claims are small, scarcely of a size warranting the expense of seeking redress alone. But by joining together with others similarly circumstanced, employees can gain effective redress for wage underpayment commonly experienced. To block such concerted action, their employers required them to sign, as a condition of employment, arbitration agreements banning collective judicial and arbitral proceedings of any kind. The question presented: Does the Federal Arbitration Act permit employers to insist that their employees, whenever seeking redress for commonly experienced wage loss, go it alone, never mind the right secured to employees by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) “to engage in … concerted activities” for their “mutual aid or protection”? The answer should be a resounding “No.”

In the NLRA and its forerunner, the Norris-LaGuardia Act (NLGA), 29 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., Congress acted on an acute awareness: For workers striving to gain from their employers decent terms and conditions of employment, there is strength in numbers. A single employee, Congress understood, is disarmed in dealing with an employer. The Court today subordinates employee-protective labor legislation to the Arbitration Act. In so doing, the Court forgets the labor market imbalance that gave rise to the NLGA and the NLRA, and ignores the destructive consequences of diminishing the right of employees “to band together in confronting an employer.” Congressional correction of the Court’s elevation of the FAA over workers’ rights to act in concert is urgently in order.

To explain why the Court’s decision is egregiously wrong, I first refer to the extreme imbalance once prevalent in our Nation’s workplaces, and Congress’ aim in the NLGA and the NLRA to place employers and employees on a more equal footing. I then explain why the Arbitration Act, sensibly read, does not shrink the NLRA’s protective sphere. […]

The end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th was a tumultuous era in the history of our Nation’s labor relations. Under economic conditions then prevailing, workers often had to accept employment on whatever terms employers dictated. Aiming to secure better pay, shorter workdays, and safer workplaces, workers increasingly sought to band together to make their demands effective. […]

Early legislative efforts to protect workers’ rights to band together were unavailing. […]

In the 1930’s, legislative efforts to safeguard vulnerable workers found more receptive audiences. As the Great Depression shifted political winds further in favor of worker-protective laws, Congress passed two statutes aimed at protecting employees’ associational rights. First, in 1932, Congress passed the NLGA, which regulates the employer-employee relationship indirectly. Section 2 of the Act declares:

“Whereas … the individual unorganized worker is commonly helpless to exercise actual liberty of contract and to protect his freedom of labor, … it is necessary that he have full freedom of association, self-organization, and designation of representatives of his own choosing, … and that he shall be free from the interference, restraint, or coercion of employers … in the designation of such representatives or in self-organization or in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” 29 U.S.C. § 102. …

But Congress did so three years later, in 1935, when it enacted the NLRA. Relevant here, § 7 of the NLRA guarantees employees “the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” 29 U.S.C. § 157 (emphasis added). Section 8(a)(1) safeguards those rights by making it an “unfair labor practice” for an employer to “interfere with, restrain, or coerce employees in the exercise of the rights guaranteed in [§ 7].” § 158(a)(1). […]

Despite the NLRA’s prohibitions, the employers in the cases now before the Court required their employees to sign contracts stipulating to submission of wage and hours claims to binding arbitration, and to do so only one-by-one. When employees subsequently filed wage and hours claims in federal court and sought to invoke the collective-litigation procedures provided for in the FLSA and Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the employers moved to compel individual arbitration. The Arbitration Act, in their view, requires courts to enforce their take-it-or-leave-it arbitration agreements as written, including the collective-litigation abstinence demanded therein.

In resisting enforcement of the group-action foreclosures, the employees involved in this litigation do not urge that they must have access to a judicial forum. They argue only that the NLRA prohibits their employers from denying them the right to pursue work-related claims in concert in any forum. If they may be stopped by employer-dictated terms from pursuing collective procedures in court, they maintain, they must at least have access to similar procedures in an arbitral forum. […]

Suits to enforce workplace rights collectively fit comfortably under the umbrella “concerted activities for the purpose of … mutual aid or protection.” 29 U.S.C. § 157. “Concerted” means “[p]lanned or accomplished together; combined.” American Heritage Dictionary 381 (5th ed. 2011). “Mutual” means “reciprocal.” Id., at 1163. When employees meet the requirements for litigation of shared legal claims in joint, collective, and class proceedings, the litigation of their claims is undoubtedly “accomplished together.” By joining hands in litigation, workers can spread the costs of litigation and reduce the risk of employer retaliation. […]

In face of the NLRA’s text, history, purposes, and longstanding construction, the Court nevertheless concludes that collective proceedings do not fall within the scope of § 7. None of the Court’s reasons for diminishing § 7 should carry the day. […]

The inevitable result of today’s decision will be the underenforcement of federal and state statutes designed to advance the well-being of vulnerable workers. […]

* * *

If these untoward consequences stemmed from legislative choices, I would be obliged to accede to them. But the edict that employees with wage and hours claims may seek relief only one-by-one does not come from Congress. It is the result of take-it-or-leave-it labor contracts harking back to the type called “yellow dog,” and of the readiness of this Court to enforce those unbargained-for agreements. The FAA demands no such suppression of the right of workers to take concerted action for their “mutual aid or protection.” […]

Notes & Questions

Epic Systems involves a purported clash between two federal statutes: the Federal Arbitration Act and the National Labor Relations Act. The Court held that the FAA applies unless there is a generally applicable defense (such as unconscionability, the doctrine at issue in Ferguson). What did the employees argue was their generally applicable defense?

The Court held that the employees defense was contract-specific rather than general. Why?

6.2 Summary Judgment

At the close of discovery, the parties have another chance to dispose of the case without the need for a jury: summary judgment. Rule 56(a) provides that either party may move for summary judgment by showing “that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact” and therefore that “the movant is entitle to judgment as a matter of law.”

In many ways, summary judgment is a later-in-time version of a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6). Both motions ask the court to take the facts as the non-moving party has presented them and then determine whether the case can survive as a legal matter. The key difference between a summary judgment motion and Rule 12(b)(6) motion is that the latter is tested against the allegations in the complaint, while the former is tested against evidence, which must be submitted to the court as part of the briefing on the motion. See Rule 56(c).

Like the Rule 12(b)(6) motion, the standards governing Rule 56 have changed more dramatically than the text of the Rule has. The cases that follow trace the development of summary judgment procedure in federal court. As you read them, pay close attention to (1) the evidence adduced by the non-moving party; and (2) the arguments made by the party seeking summary judgment.

Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co.

MR. JUSTICE HARLAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

1 Rev. Stat. § 1979, 42 U.S.C. § 1983 provides:

“Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.”

Petitioner, Sandra Adickes, a white school teacher from New York, brought this suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York against respondent S. H. Kress & Co. (“Kress”) to recover damages under 42 U.S.C. § 19831 for an alleged violation of her constitutional rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The suit arises out of Kress’ refusal to serve lunch to Miss Adickes at its restaurant facilities in its Hattiesburg, Mississippi, store on August 14, 1964, and Miss Adickes’ subsequent arrest upon her departure from the store by the Hattiesburg police on a charge of vagrancy. At the time of both the refusal to serve and the arrest, Miss Adickes was with six young people, all Negroes, who were her students in a Mississippi “Freedom School” where she was teaching that summer. Unlike Miss Adickes, the students were offered service, and were not arrested.

Petitioner’s complaint had two counts, each bottomed on § 1983, and each alleging that Kress had deprived her of the right under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment not to be discriminated against on the basis of race. […]

The second count of her complaint, alleging that both the refusal of service and her subsequent arrest were the product of a conspiracy between Kress and the Hattiesburg police, was dismissed before trial on a motion for summary judgment. The District Court ruled that petitioner had “failed to allege any facts from which a conspiracy might be inferred.” This determination was unanimously affirmed by the Court of Appeals.

Miss Adickes, in seeking review here, claims that the District Court erred […] in granting summary judgment on the conspiracy count. [W]e now reverse and remand for further proceedings on each of the two counts.

As explained in Part I, because the respondent failed to show the absence of any disputed material fact, we think the District Court erred in granting summary judgment. […]

I

Briefly stated, the conspiracy count of petitioner’s complaint made the following allegations: While serving as a volunteer teacher at a “Freedom School” for Negro children in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, petitioner went with six of her students to the Hattiesburg Public Library at about noon on August 14, 1964. The librarian refused to allow the Negro students to use the library, and asked them to leave. Because they did not leave, the librarian called the Hattiesburg chief of police who told petitioner and her students that the library was closed, and ordered them to leave. From the library, petitioner and the students proceeded to respondent’s store where they wished to eat lunch. According to the complaint, after the group sat down to eat, a policeman came into the store “and observed [Miss Adickes] in the company of the Negro students.” A waitress then came to the booth where petitioner was sitting, took the orders of the Negro students, but refused to serve petitioner because she was a white person “in the company of Negroes.” The complaint goes on to allege that after this refusal of service, petitioner and her students left the Kress store. When the group reached the sidewalk outside the store, “the Officer of the Law who had previously entered [the] store” arrested petitioner on a groundless charge of vagrancy and took her into custody.

On the basis of these underlying facts petitioner alleged that Kress and the Hattiesburg police had conspired (1) “to deprive [her] of her right to enjoy equal treatment and service in a place of public accommodation”; and (2) to cause her arrest “on the false charge of vagrancy.”

[…]

SUMMARY JUDGMENT

We now proceed to consider whether the District Court erred in granting summary judgment on the conspiracy count. In granting respondent’s motion, the District Court simply stated that there was “no evidence in the complaint or in the affidavits and other papers from which a ‘reasonably-minded person’ might draw an inference of conspiracy.” Our own scrutiny of the factual allegations of petitioner’s complaint, as well as the material found in the affidavits and depositions presented by Kress to the District Court, however, convinces us that summary judgment was improper here, for we think respondent failed to carry its burden of showing the absence of any genuine issue of fact. Before explaining why this is so, it is useful to state the factual arguments, made by the parties concerning summary judgment, and the reasoning of the courts below.

In moving for summary judgment, Kress argued that “uncontested facts” established that no conspiracy existed between any Kress employee and the police. To support this assertion, Kress pointed first to the statements in the deposition of the store manager (Mr. Powell) that (a) he had not communicated with the police, and that (b) he had, by a prearranged tacit signal, ordered the food counter supervisor to see that Miss Adickes was refused service only because he was fearful of a riot in the store by customers angered at seeing a “mixed group” of whites and blacks eating together. Kress also relied on affidavits from the Hattiesburg chief of police, and the two arresting officers, to the effect that store manager Powell had not requested that petitioner be arrested. Finally, Kress pointed to the statements in petitioner’s own deposition that she had no knowledge of any communication between any Kress employee and any member of the Hattiesburg police, and was relying on circumstantial evidence to support her contention that there was an arrangement between Kress and the police.

Petitioner, in opposing summary judgment, pointed out that respondent had failed in its moving papers to dispute the allegation in petitioner’s complaint, a statement at her deposition, and an unsworn statement by a Kress employee, all to the effect that there was a policeman in the store at the time of the refusal to serve her, and that this was the policeman who subsequently arrested her. Petitioner argued that although she had no knowledge of an agreement between Kress and the police, the sequence of events created a substantial enough possibility of a conspiracy to allow her to proceed to trial, especially given the fact that the non-circumstantial evidence of the conspiracy could only come from adverse witnesses. Further, she submitted an affidavit specifically disputing the manager’s assertion that the situation in the store at the time of the refusal was “explosive,” thus creating an issue of fact as to what his motives might have been in ordering the refusal of service.

We think that on the basis of this record, it was error to grant summary judgment. As the moving party, respondent had the burden of showing the absence of a genuine issue as to any material fact, and for these purposes the material it lodged must be viewed in the light most favorable to the opposing party. Respondent here did not carry its burden because of its failure to foreclose the possibility that there was a policeman in the Kress store while petitioner was awaiting service, and that this policeman reached an understanding with some Kress employee that petitioner not be served.

It is true that Mr. Powell, the store manager, claimed in his deposition that he had not seen or communicated with a policeman prior to his tacit signal to Miss Baggett, the supervisor of the food counter. But respondent did not submit any affidavits from Miss Baggett, or from Miss Freeman, the waitress who actually refused petitioner service, either of whom might well have seen and communicated with a policeman in the store. Further, we find it particularly noteworthy that the two officers involved in the arrest each failed in his affidavit to foreclose the possibility (1) that he was in the store while petitioner was there; and (2) that, upon seeing petitioner with Negroes, he communicated his disapproval to a Kress employee, thereby influencing the decision not to serve petitioner.

Given these unexplained gaps in the materials submitted by respondent, we conclude that respondent failed to fulfill its initial burden of demonstrating what is a critical element in this aspect of the case—that there was no policeman in the store. If a policeman were present, we think it would be open to a jury, in light of the sequence that followed, to infer from the circumstances that the policeman and a Kress employee had a “meeting of the minds” and thus reached an understanding that petitioner should be refused service. Because “[o]n summary judgment the inferences to be drawn from the underlying facts contained in [the moving party’s] materials must be viewed in the light most favorable to the party opposing the motion,” we think respondent’s failure to show there was no policeman in the store requires reversal.

18 The amendment added the following to Rule 56(e):

“When a motion for summary judgment is made and supported as provided in this rule, an adverse party may not rest upon the mere allegations or denials of his pleading, but his response, by affidavits or as otherwise provided in this rule, must set forth specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial. If he does not so respond, summary judgment, if appropriate, shall be entered against him.”

[Ed. note: the 2010 amendments moved the substance of this part of Rule 56(e) to Rule 56(c)(1).]

20 The purpose of the 1963 amendment was to overturn a line of cases, primarily in the Third Circuit, that had held that a party opposing summary judgment could successfully create a dispute as to a material fact asserted in an affidavit by the moving party simply by relying on a contrary allegation in a well-pleaded complaint. E.g., Frederick Hart & Co. v. Recordgraph Corp., 169 F.2d 580 ([3d Cir.]1948); United States ex rel. Kolton v. Halpern, 260 F.2d 590 ([3d Cir.] 1958). See Advisory Committee Note on 1963 Amendment to subdivision (e) of Rule 56.

Pointing to Rule 56(e), as amended in 1963,18 respondent argues that it was incumbent on petitioner to come forward with an affidavit properly asserting the presence of the policeman in the store, if she were to rely on that fact to avoid summary judgment. Respondent notes in this regard that none of the materials upon which petitioner relied met the requirements of Rule 56(e).

This argument does not withstand scrutiny, however, for both the commentary on and background of the 1963 amendment conclusively show that it was not intended to modify the burden of the moving party under Rule 56([a]) to show initially the absence of a genuine issue concerning any material fact.20 The Advisory Committee note on the amendment states that the changes were not designed to “affect the ordinary standards applicable to the summary judgment.” And, in a comment directed specifically to a contention like respondent’s the Committee stated that “[w]here the evidentiary matter in support of the motion does not establish the absence of a genuine issue, summary judgment must be denied even if no opposing evidentiary matter is presented.” Because respondent did not meet its initial burden of establishing the absence of a policeman in the store, petitioner here was not required to come forward with suitable opposing affidavits.

If respondent had met its initial burden by, for example, submitting affidavits from the policemen denying their presence in the store at the time in question, Rule 56(e) would then have required petitioner to have done more than simply rely on the contrary allegation in her complaint. To have avoided conceding this fact for purposes of summary judgment, petitioner would have had to come forward with either (1) the affidavit of someone who saw the policeman in the store or (2) an affidavit under Rule 56([d]) explaining why at that time it was impractical to do so. Even though not essential here to defeat respondent’s motion, the submission of such an affidavit would have been the preferable course for petitioner’s counsel to have followed. As one commentator has said:

“It has always been perilous for the opposing party neither to proffer any countering evidentiary materials nor file a 56([d]) affidavit. And the peril rightly continues [after the amendment to Rule 56(e)]. Yet the party moving for summary judgment has the burden to show that he is entitled to judgment under established principles; and if he does not discharge that burden then he is not entitled to judgment. No defense to an insufficient showing is required.”

6 J. Moore, Federal Practice ¶ 56.22 [2], pp. 2824–2825 (2d ed. 1966).

[…]

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is reversed, and the case is remanded to that court for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

MR. JUSTICE MARSHALL took no part in the decision of this case.

MR. JUSTICE BLACK, concurring in the judgment.

The petitioner, Sandra Adickes, brought suit against the respondent, S. H. Kress & Co., to recover damages for alleged violations of 42 U.S.C. § 1983. In one count of her complaint she alleged that a police officer of the City of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, had conspired with employees of Kress to deprive her of rights secured by the Constitution and that this joint action of a state official and private individuals was sufficient to constitute a violation of § 1983. […] The trial judge granted a motion for summary judgment in favor of Kress on the conspiracy allegation […]. [That decision] rested on [the] conclusion[] that there were no issues of fact supported by sufficient evidence to require a jury trial. I think the trial court and the Court of Appeals which affirmed were wrong in allowing summary judgment on the conspiracy allegation. […] In my judgment, on this record, petitioner should have been permitted to have the jury consider […] her claims.

Summary judgments may be granted only when “the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, together with the affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact … .” Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 56([a]). Petitioner in this case alleged that she went into Kress in the company of Negroes and that the waitress refused to serve her, stating “[w]e have to serve the colored, but we are not going to serve the whites that come in with them.” Petitioner then alleged that she left the store with her friends and as soon as she stepped outside a policeman arrested her and charged her with vagrancy. On the basis of these facts she argued that there was a conspiracy between the store and the officer to deprive her of federally protected rights. The store filed affidavits denying any such conspiracy and the trial court granted the motion for summary judgment, concluding that petitioner had not alleged any basic facts sufficient to support a finding of conspiracy.

The existence or nonexistence of a conspiracy is essentially a factual issue that the jury, not the trial judge, should decide. In this case petitioner may have had to prove her case by impeaching the store’s witnesses and appealing to the jury to disbelieve all that they said was true in the affidavits. The right to confront, cross-examine and impeach adverse witnesses is one of the most fundamental rights sought to be preserved by the Seventh Amendment provision for jury trials in civil cases. The advantages of trial before a live jury with live witnesses, and all the possibilities of considering the human factors, should not be eliminated by substituting trial by affidavit and the sterile bareness of summary judgment. “It is only when the witnesses are present and subject to cross-examination that their credibility and the weight to be given their testimony can be appraised. Trial by affidavit is no substitute for trial by jury which so long has been the hallmark of ‘even handed justice.’”

Notes & Questions

What was S.H. Kress’s argument for why there was no genuine dispute as to any material fact? Did Kress rely on its own evidence or legal argument?

What evidence did Adickes present to resist summary judgment?

Did the Court find that there was an agreement between the police and the store employees? If not, why did the Court hold that summary judgment was not appropriate?

With summary judgment motions, as with all motions, the party filing the motion has the burden of persuasion. If the moving party can’t convince the court to grant summary judgment, it will lose. But there is another kind of burden: a burden of production. And unlike the burden of persuasion, the burden of production can shift from the moving party to the nonmoving party. It does so when the moving party has made a prima facie showing that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact. At that point, the burden of production shifts to the non-moving party, who then must come forward with evidence of her own showing that there is, in material fact, a genuine dispute. The next case, which stands in significant tension with Adickes, explores what Rule 56 demands of a party seeking summary judgment before the burden of production will shift.

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett

JUSTICE REHNQUIST delivered the opinion of the Court.

[…] Respondent commenced this lawsuit in September 1980, alleging that the death in 1979 of her husband, Louis H. Catrett, resulted from his exposure to products containing asbestos manufactured or distributed by 15 named corporations. Respondent’s complaint sounded in negligence, breach of warranty, and strict liability. […] Petitioner’s motion [for summary judgment] […] argued that summary judgment was proper because respondent had “failed to produce evidence that any [Celotex] product … was the proximate cause of the injuries alleged […].” In particular, petitioner noted that respondent had failed to identify, in answering interrogatories specifically requesting such information, any witnesses who could testify about the decedent’s exposure to petitioner’s asbestos products. In response to petitioner’s summary judgment motion, respondent then produced three documents which she claimed “demonstrate that there is a genuine material factual dispute” as to whether the decedent had ever been exposed to petitioner’s asbestos products. The three documents included a transcript of a deposition of the decedent, a letter from an official of one of the decedent’s former employers whom petitioner planned to call as a trial witness, and a letter from an insurance company to respondent’s attorney, all tending to establish that the decedent had been exposed to petitioner’s asbestos products in Chicago during 1970–1971. Petitioner, in turn, argued that the three documents were inadmissible hearsay and thus could not be considered in opposition to the summary judgment motion.

[…] [T]he District Court granted […] [the] motion because “there [was] no showing that the plaintiff was exposed to the defendant Celotex’s product in the District of Columbia or elsewhere within the statutory period.” [The court of appeals reversed.] According to the majority, Rule 56(e) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and this Court’s decision in Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144, 159 (1970), establish that “the party opposing the motion for summary judgment bears the burden of responding only after the moving party has met its burden of coming forward with proof of the absence of any genuine issues of material fact.” The majority therefore declined to consider petitioner’s argument that none of the evidence produced by respondent in opposition to the motion for summary judgment would have been admissible at trial. […]

We think that the position taken by the majority of the Court of Appeals is inconsistent with the standard for summary judgment set forth in Rule 56([a]) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. […] In our view, the plain language of Rule 56([a]) mandates the entry of summary judgment, after adequate time for discovery […] against a party who fails to make a showing sufficient to establish the existence of an element essential to that party’s case, and on which that party will bear the burden of proof at trial. In such a situation, there can be “no genuine issue as to any material fact,” since a complete failure of proof concerning an essential element of the nonmoving party’s case necessarily renders all other facts immaterial. The moving party is “entitled to a judgment as a matter of law” because the nonmoving party has failed to make a sufficient showing on an essential element of her case with respect to which she has the burden of proof. “[The] standard [for granting summary judgment] mirrors the standard for a directed verdict under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 50(a) … .” Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 250 (1986).

* [Quoting the text of rule 56(c) at the time. –Ed.]

Of course, a party seeking summary judgment always bears the initial responsibility of informing the district court of the basis for its motion, and identifying those portions of [“particular parts of materials in the record, including depositions, documents, electronically stored information, affidavits or declarations, stipulations … admissions, interrogatory answers [quoting Rule 56(c)(1)]”] which it believes demonstrate the absence of a genuine issue of material [dispute]. But unlike the Court of Appeals, we find no express or implied requirement in Rule 56 that the moving party support its motion with affidavits or other similar materials negating the opponent’s claim. On the contrary, Rule 56(c), which refers to “the affidavits, if any”* (emphasis added), suggests the absence of such a requirement. And if there were any doubt about the meaning of Rule 56(c) in this regard, such doubt is clearly removed by Rules 56(a) and (b), which provide that claimants and defendants, respectively, may move for summary judgment “with or without supporting affidavits” (emphasis added). The import of these subsections is that, regardless of whether the moving party accompanies its summary judgment motion with affidavits, the motion may, and should, be granted so long as whatever is before the district court demonstrates that the standard for the entry of summary judgment, as set forth in Rule 56(c), is satisfied. One of the principal purposes of the summary judgment rule is to isolate and dispose of factually unsupported claims or defenses, and we think it should be interpreted in a way that allows it to accomplish this purpose.

[…]

We do not mean that the nonmoving party must produce evidence in a form that would be admissible at trial in order to avoid summary judgment. Obviously, Rule 56 does not require the nonmoving party to depose her own witnesses. Rule 56(e) permits a proper summary judgment motion to be opposed by any of the kinds of evidentiary materials listed in Rule 56(c), except the mere pleadings themselves […].

The Court of Appeals in this case felt itself constrained, however, by language in our decision in Adickes. There we held that summary judgment had been improperly entered in favor of the defendant restaurant in an action brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. In the course of its opinion, the Adickes Court said that “both the commentary on and the background of the 1963 amendment conclusively show that it was not intended to modify the burden of the moving party … to show initially the absence of a genuine issue concerning any material fact.” We think that this statement is accurate in a literal sense […]. But we do not think the Adickes language quoted above should be construed to mean that the burden is on the party moving for summary judgment to produce evidence showing the absence of a genuine issue of material fact, even with respect to an issue on which the nonmoving party bears the burden of proof. Instead, as we have explained, the burden on the moving party may be discharged by “showing”—that is, pointing out to the district court—that there is an absence of evidence to support the nonmoving party’s case.

[…]

Our conclusion is bolstered by the fact that district courts are widely acknowledged to possess the power to enter summary judgments sua sponte, so long as the losing party was on notice that she had to come forward with all of her evidence. It would surely defy common sense to hold that the District Court could have entered summary judgment sua sponte in favor of petitioner in the instant case, but that petitioner’s filing of a motion requesting such a disposition precluded the District Court from ordering it.

Respondent commenced this action in September 1980, and petitioner’s motion was filed in September 1981. The parties had conducted discovery, and no serious claim can be made that respondent was in any sense “railroaded” by a premature motion for summary judgment. Any potential problem with such premature motions can be adequately dealt with under Rule 56(f), which allows a summary judgment motion to be denied, or the hearing on the motion to be continued, if the nonmoving party has not had an opportunity to make full discovery.

In this Court, respondent’s brief and oral argument have been devoted as much to the proposition that an adequate showing of exposure to petitioner’s asbestos products was made as to the proposition that no such showing should have been required. But the Court of Appeals declined to address either […]. We think the Court of Appeals with its superior knowledge of local law is better suited than we are to make these determinations in the first instance.

[…] Summary judgment procedure is properly regarded not as a disfavored procedural shortcut, but rather as an integral part of the Federal Rules as a whole, which are designed “to secure the just, speedy and inexpensive determination of every action.” Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 1. Before the shift to “notice pleading” accomplished by the Federal Rules, motions to dismiss a complaint or to strike a defense were the principal tools by which factually insufficient claims or defenses could be isolated and prevented from going to trial with the attendant unwarranted consumption of public and private resources. But with the advent of “notice pleading,” the motion to dismiss seldom fulfills this function any more, and its place has been taken by the motion for summary judgment. Rule 56 must be construed with due regard not only for the rights of persons asserting claims and defenses that are adequately based in fact to have those claims and defenses tried to a jury, but also for the rights of persons opposing such claims and defenses to demonstrate in the manner provided by the Rule, prior to trial, that the claims and defenses have no factual basis.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is accordingly reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

JUSTICE WHITE, concurring.

[I agree with the Court’s holding, but write separately to emphasize that] the movant must discharge the burden the Rules place upon him: It is not enough to move for summary judgment without supporting the motion in any way or with a conclusory assertion that the plaintiff has no evidence to prove his case.

[…] Celotex does not dispute that if respondent has named a witness to support her claim, summary judgment should not be granted without Celotex[‘s] somehow showing that the named witness’ possible testimony raises no genuine issue of material fact. It asserts, however, that respondent has failed on request to produce any basis for her case. Respondent, on the other hand, does not contend that she was not obligated to reveal her witnesses and evidence but insists that she has revealed enough to defeat the motion for summary judgment. Because the Court of Appeals found it unnecessary to address this aspect of the case, I agree that the case should be remanded for further proceedings.

JUSTICE BRENNAN, with whom THE CHIEF JUSTICE and JUSTICE BLACKMUN join, dissenting.

[…]

Notes & Questions

What was Celotex’s argument for why there was no genuine dispute as to any material fact? Did Celotex rely on its own evidence or legal argument?

What evidence did Catrett present to resist summary judgment? What did the Court say was wrong with that evidence? Why wasn’t it enough to defeat summary judgment?

Celotex was one of a trilogy of summary judgment cases decided by the Supreme Court in 1986. Each is important.

Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574 (1986), is to summary judgment as Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly is to the motion to dismiss for failure to state claim. Both cases held, in their respective procedural postures, that only a plausible showing of conspiracy will be enough to survive dismissal. In Matsushita, the plaintiffs offered circumstantial evidence of a conspiracy, which the court rejected because the same evidence was consistent with parallel conduct, which is lawful.

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986), clarified that courts ruling on a motion for summary judgment must apply the standard of proof that would apply at trial. The claims in Anderson sounded in libel, which carries a heighted burden of proof on the plaintiff: clear and convincing evidence. The Court held that a plaintiff held to such a standard of proof must satisfy it to win summary judgment.

Tolan v. Cotton

PER CURIAM.

During the early morning hours of New Year’s Eve, 2008, police sergeant Jeffrey Cotton fired three bullets at Robert Tolan; one of those bullets hit its target and punctured Tolan’s right lung. At the time of the shooting, Tolan was unarmed on his parents’ front porch about 15 to 20 feet away from Cotton. Tolan sued, alleging that Cotton had exercised excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment. The District Court granted summary judgment to Cotton. In articulating the factual context of the case, the Fifth Circuit failed to adhere to the axiom that in ruling on a motion for summary judgment, “[t]he evidence of the nonmovant is to be believed, and all justifiable inferences are to be drawn in his favor.” Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 255 (1986). For that reason, we vacate its decision and remand the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

I

A

The following facts, which we view in the light most favorable to Tolan, are taken from the record evidence and the opinions below. At around 2:00 on the morning of December 31, 2008, John Edwards, a police officer, was on patrol in Bellaire, Texas, when he noticed a black Nissan sport utility vehicle turning quickly onto a residential 580street. The officer watched the vehicle park on the side of the street in front of a house. Two men exited: Tolan and his cousin, Anthony Cooper.

Edwards attempted to enter the license plate number of the vehicle into a computer in his squad car. But he keyed an incorrect character; instead of entering plate number 696BGK, he entered 695BGK. That incorrect number matched a stolen vehicle of the same color and make. This match caused the squad car’s computer to send an automatic message to other police units, informing them that Edwards had found a stolen vehicle.

Edwards exited his cruiser, drew his service pistol and ordered Tolan and Cooper to the ground. He accused Tolan and Cooper of having stolen the car. Cooper responded, “That’s not true.” And Tolan explained, “That’s my car.” Tolan then complied with the officer’s demand to lie face-down on the home’s front porch.

As it turned out, Tolan and Cooper were at the home where Tolan lived with his parents. Hearing the commotion, Tolan’s parents exited the front door in their pajamas. In an attempt to keep the misunderstanding from escalating into something more, Tolan’s father instructed Cooper to lie down, and instructed Tolan and Cooper to say nothing. Tolan and Cooper then remained face-down.

Edwards told Tolan’s parents that he believed Tolan and Cooper had stolen the vehicle. In response, Tolan’s father identified Tolan as his son, and Tolan’s mother explained that the vehicle belonged to the family and that no crime had been committed. Tolan’s father explained, with his hands in the air, “[T]his is my nephew. This is my son. We live here. This is my house.” Tolan’s mother similarly offered, “[S]ir this is a big mistake. This car is not stolen. … That’s our car.”

While Tolan and Cooper continued to lie on the ground in silence, Edwards radioed for assistance. Shortly thereafter, Sergeant Jeffrey Cotton arrived on the scene and drew his pistol. Edwards told Cotton that Cooper and Tolan had exited a stolen vehicle. Tolan’s mother reiterated that she and her husband owned both the car Tolan had been driving and the home where these events were unfolding. Cotton then ordered her to stand against the family’s garage door. In response to Cotton’s order, Tolan’s mother asked, “[A]re you kidding me? We’ve lived her[e] 15 years. We’ve never had anything like this happen before.”

The parties disagree as to what happened next. Tolan’s mother and Cooper testified during Cotton’s criminal trial that Cotton grabbed her arm and slammed her against the garage door with such force that she fell to the ground. Tolan similarly testified that Cotton pushed his mother against the garage door. In addition, Tolan offered testimony from his mother and photographic evidence to demonstrate that Cotton used enough force to leave bruises on her arms and back that lasted for days. By contrast, Cotton testified in his deposition that when he was escorting the mother to the garage, she flipped her arm up and told him to get his hands off her. He also testified that he did not know whether he left bruises but believed that he had not.

The parties also dispute the manner in which Tolan responded. Tolan testified in his deposition and during the criminal trial that upon seeing his mother being pushed, he rose to his knees. Edwards and Cotton testified that Tolan rose to his feet.

Both parties agree that Tolan then exclaimed, from roughly 15 to 20 feet away, “[G]et your fucking hands off my mom.” The parties also agree that Cotton then drew 581his pistol and fired three shots at Tolan. Tolan and his mother testified that these shots came with no verbal warning. One of the bullets entered Tolan’s chest, collapsing his right lung and piercing his liver. While Tolan survived, he suffered a life-altering injury that disrupted his budding professional baseball career and causes him to experience pain on a daily basis.

B

In May 2009, Cooper, Tolan, and Tolan’s parents filed this suit in the Southern District of Texas, alleging claims under Rev. Stat. § 1979, 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Tolan claimed, among other things, that Cotton had used excessive force against him in violation of the Fourth Amendment. After discovery, Cotton moved for summary judgment.

The District Court granted summary judgment to Cotton. […] The Fifth Circuit affirmed […]. […]

In reaching this conclusion, the Fifth Circuit began by noting that at the time Cotton shot Tolan, “it was … clearly established that an officer had the right to use deadly force if that officer harbored an objective and reasonable belief that a suspect presented an ‘immediate threat to [his] safety.’” The Court of Appeals reasoned that Tolan failed to overcome th[at] bar because “an objectively-reasonable officer in Sergeant Cotton’s position could have … believed” that Tolan “presented an ‘immediate threat to the safety of the officers.’” In support of this conclusion, the court relied on the following facts: the front porch had been “dimly-lit”; Tolan’s mother had “refus[ed] orders to remain quiet and calm”; and Tolan’s words had amounted to a “verba[l] threa[t].” Most critically, the court also relied on the purported fact that Tolan was “moving to intervene in” Cotton’s handling of his mother, and that Cotton therefore could reasonably have feared for his life. Accordingly, the court held, Cotton did not violate clearly established law in shooting Tolan. […]

II

[…]

B

In holding that Cotton’s actions did not violate clearly established law, the Fifth Circuit failed to view the evidence at summary judgment in the light most favorable to Tolan with respect to the central facts of this case. By failing to credit evidence that contradicted some of its key factual conclusions, the court improperly “weigh[ed] the evidence” and resolved disputed issues in favor of the moving party, Anderson, 477 U.S., at 249.

First, the court relied on its view that at the time of the shooting, the Tolans’ front porch was “dimly-lit.” The court appears to have drawn this assessment from Cotton’s statements in a deposition that when he fired at Tolan, the porch was “‘fairly dark,’” and lit by a gas lamp that was “‘decorative.’” In his own deposition, however, Tolan’s father was asked whether the gas lamp was in fact “more decorative than illuminating.” He said that it was not. Moreover, Tolan stated in his deposition that two floodlights shone on the driveway during the incident, and Cotton acknowledged that there were two motion-activated lights in front of the house. And Tolan confirmed that at the time of the shooting, he was “not in darkness.”

Second, the Fifth Circuit stated that Tolan’s mother “refus[ed] orders to remain quiet and calm,” thereby “compound[ing]” Cotton’s belief that Tolan “presented an immediate threat to the safety of the officers.” But here, too, the court did not credit directly contradictory evidence. Although the parties agree that Tolan’s mother repeatedly informed officers that Tolan was her son, that she lived in the home in front of which he had parked, and that the vehicle he had been driving belonged to her and her husband, there is a dispute as to how calmly she provided this information. Cotton stated during his deposition that Tolan’s mother was “very agitated” when she spoke to the officers. By contrast, Tolan’s mother testified at Cotton’s criminal trial that she was neither “aggravated” nor “agitated.”

Third, the Court concluded that Tolan was “shouting,” and “verbally threatening” the officer, in the moments before the shooting. The court noted, and the parties agree, that while Cotton was grabbing the arm of his mother, Tolan told Cotton, “[G]et your fucking hands off my mom.” But Tolan testified that he “was not screaming.” And a jury could reasonably infer that his words, in context, did not amount to a statement of intent to inflict harm. Tolan’s mother testified in Cotton’s criminal trial that he slammed her against a garage door with enough force to cause bruising that lasted for days. A jury could well have concluded that a reasonable officer would have heard Tolan’s words not as a threat, but as a son’s plea not to continue any assault of his mother.

Fourth, the Fifth Circuit inferred that at the time of the shooting, Tolan was “moving to intervene in Sergeant Cotton’s” interaction with his mother. The court appears to have credited Edwards’ account that at the time of the shooting, Tolan was on both feet “[i]n a crouch” or a “charging position” looking as if he was going to move forward. Tolan testified at trial, however, that he was on his knees when Cotton shot him, a fact corroborated by his mother. Tolan also testified in his deposition that he “wasn’t going anywhere,” and emphasized that he did not “jump up.”

Considered together, these facts lead to the inescapable conclusion that the court below credited the evidence of the party seeking summary judgment and failed properly to acknowledge key evidence offered by the party opposing that motion. And while “this Court is not equipped to correct every perceived error coming from the lower federal courts,” we intervene here because the opinion below reflects a clear misapprehension of summary judgment standards in light of our precedents.