14 The Erie Doctrine

This section explores the Erie doctrine, one of the murkiest and most important features of our federal system of courts. The gist of the Erie doctrine can be stated in simplified form:

When a federal court sits in diversity, it applies state substantive and federal procedural law.

Working out that simple statement in practice, however, is quite tricky.

14.1 Ascertaining State Law

One of the most surprising features of our federal system of courts is that we not only have both state and federal courts, we also have both state and federal law. Confusingly, questions of federal law are often addressed by state courts, and questions of state law are often addressed by federal courts (as is the case with diversity jurisdiction). In other words, just because you know the forum doesn’t mean you know the substantive law—and vice versa.

The question of which body of substantive law will apply in litigation is known as “choice of law.” When we are trying to decide which of several states’ laws might apply, the question is more specifically known as horizontal choice of law. By contrast, the choice between state and federal law is known as vertical choice of law. These two choice of law questions are related, but they are answered using different analytical tools under our constitutional system.

Article III of the U.S. Constitution grants to Congress the decision whether to create federal courts other than the Supreme Court. Since the first Congress, the legislature has used this power to establish a variety of lower federal courts. The first statute to do so was the Judiciary Act of 1789, a statute that continues to influence the structure of federal courts today. Among its many provisions, Section 34 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 included the first version of what is now known as the Rules of Decision Act. That provision, currently codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1652, provides:

The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

The Rules of Decision Act specifies that, unless federal law applies, state law governs—even in federal court. But the Rules of Decision Act is not entirely clear about what counts as the “laws of the several states.” Surely that category includes state constitutions and statutes. But does it include judicial precedent issued by state courts? And how does the common law fit into all of this? If state judges interpret the common law differently from federal judges, whose interpretation controls when litigation is brought in federal court?

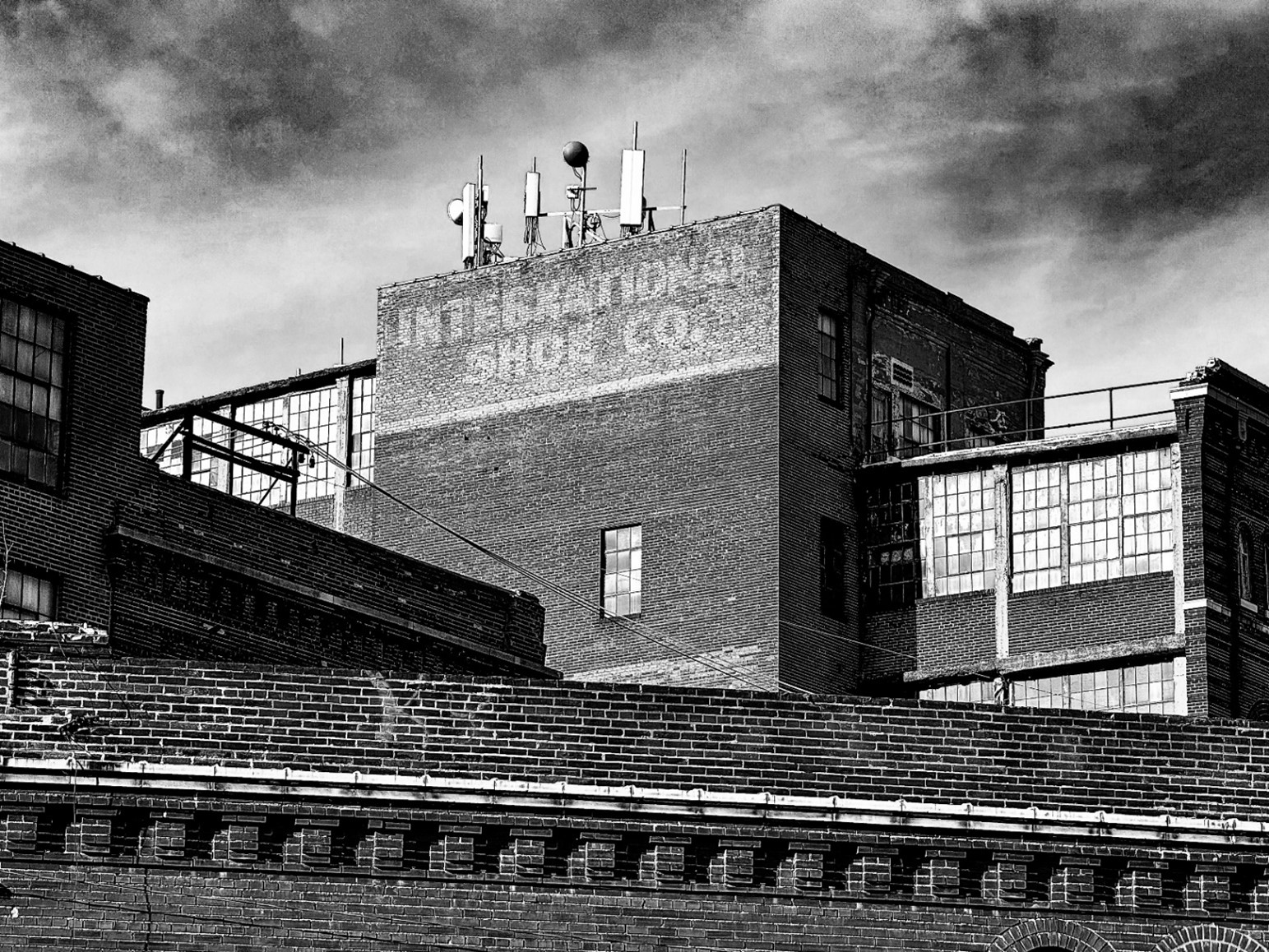

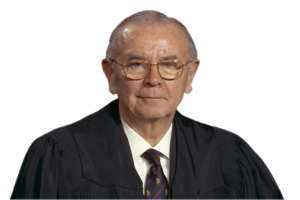

From 1841 until 1938, the Supreme Court held that judicial precedent interpreting the common law did not count as the “laws of the several states” for purposes of the Rules of Decision Act. The groundbreaking case was Swift v. Tyson, 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 1 (1842). Here is how Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black described the Swift case in 1942:

The famous case of Swift v. Tyson arose from the following rather commonplace circumstances: Two persons, [Norton] and Keith, gave Swift a bill of exchange in payment of a promissory note. The bill was accepted, or guaranteed, by another person named Tyson who in so doing meant to pay for certain land which he was purchasing from Norton and Keith. Sadly enough for Tyson, he discovered that Norton and Keith could not sell him the land because they did not own it. Therefore, when Swift sued Tyson on the bill, Tyson defended on the ground that there had been a failure of consideration to him, and that Swift could not, under these circumstances recover as a bona-fide holder for valuable consideration because Swift had paid nothing for the bill—all he had done was to accept the bill as new evidence of an old debt. The controlling issue thus became whether a new bill of exchange for an old debt was an adequate consideration for Swift’s acceptance of the bill.

The bill was made in the State of Maine; it was accepted in New York. If governed by the laws of New York, which might have been thought applicable, Swift would probably have been found to have given no consideration.*

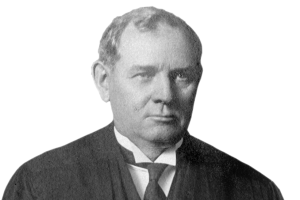

The question in Swift was which body of law applied: the common law as understood by the judges of New York, or the common law as understood by the judges of the United States. If the Rules of Decision Act’s reference to the “laws of the several states” is read to include state judicial precedent, then New York judicial precedent controlled. If not, then federal judges were free to interpret the general common law as they understood it. Writing for the majority in Swift, Justice Joseph Story—the leading expert on choice of law in that era—concluded that federal courts sitting in diversity did not need to follow New York judicial precedent when applying commercial common law:

[T]he courts of New York do not found their decisions upon this point upon any local statute, or positive, fixed, or ancient local usage: but they deduce the doctrine from the general principles of commercial law. It is, however, contended, that the thirty-fourth section of the judiciary act of 1789, ch. 20, furnishes a rule obligatory upon this court to follow the decisions of the state tribunals in all cases to which they apply. […] In order to maintain the argument, it is essential, therefore, to hold, that the word “laws,” in this section, includes within the scope of its meaning the decisions of the local tribunals. In the ordinary use of language it will hardly be contended that the decisions of courts constitute laws. They are, at most, only evidence of what the laws are, and are not of themselves laws. They are often reexamined, reversed, and qualified by the Courts themselves, whenever they are found to be either defective, or ill-founded, or otherwise incorrect. The laws of a state are more usually understood to mean the rules and enactments promulgated by the legislative authority thereof, or long established local customs having the force of laws. In all the various cases, which have hitherto come before us for decision, this court have uniformly supposed, that the true interpretation of the thirty-fourth section limited its application to state laws strictly local, that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and titles to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and titles to real estate, and other matters immovable and intraterritorial in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us, that the section did apply, or was designed to apply, to questions of a more general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or local usages of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction of ordinary contracts or other written instruments and especially to questions of general commercial law, where the state tribunals are called upon to perform the like functions as ourselves, that is, to ascertain upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true exposition of the contract or instrument, or what is the just rule furnished by the principles of commercial law to govern the case. And we have not now the slightest difficulty in holding, that this section […] is strictly limited to local statutes and local usages of the character before stated, and does not extend to contracts and other instruments of a commercial nature, the true interpretation and effect whereof are to be sought, not in the decisions of the local tribunals, but in the general principles and doctrines of commercial jurisprudence.

Swift remained governing law for nearly a century. Toward the end of its reign, commentators began to attack the intellectual foundations of Swift. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes articulated the critique best: “The common law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky but the articulate voice of some sovereign or quasi-sovereign that can be identified […]. It always is the law of some State […].” The idea is that the common law is a creature of state law, and state judges are its expositors.

Against the backdrop of these criticisms and some notorious decisions that had cast doubt on the wisdom of the Swift regime, the Court abruptly reversed course in the case that follows.

Harry James Tompkins, of Hughestown, PA, walked home from his mother-in-law’s house sometime after midnight. His route took him on a footpath that ran parallel to the Erie Railroad tracks. As Tompkins walked down the path, an Erie train—the Ashley Special No. 2499, on its way to Wilkes-Barre—wound its way down the tracks toward him. As it passed Tompkins, the train struck him, severing his right arm. Tompkins testified that he was struck by “a black object that looked like a door” extending outward from the passing train.

Whether Tompkins could recover damages for his injuries from the railroad turned on whether the law treated a pedestrian walking next to train tracks as a trespasser—as Pennsylvania courts had held—or rather as a member of the public permitted to walk along the path—as federal courts had held. If Tompkins was a trespasser, the railroad owed him a duty to avoid only wanton negligence; if he was permitted on the footpath, they owed him a duty of ordinary care.

For that reason, under the rule of Swift v. Tyson, federal courts—applying their understanding of “general law”—would hold the railroad to a higher standard than would Pennsylvania courts. Recognizing this, Tompkins’s lawyers filed suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. The case went to trial, and the jury awarded Tompkins $30,000 in damages. The railroad appealed, and the case reached the Supreme Court, which was surprisingly open to revisiting the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson.

Erie Railroad v. Tompkins

Brandeis, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question for decision is whether the oft-challenged doctrine of Swift v. Tyson shall now be disapproved.

Tompkins, a citizen of Pennsylvania, was injured on a dark night by a passing freight train of the Erie Railroad Company while walking along its right of way at Hughestown in that State. He claimed that the accident occurred through negligence in the operation, or maintenance, of the train; that he was rightfully on the premises as licensee because on a commonly used beaten footpath which ran for a short distance alongside the tracks; and that he was struck by something which looked like a door projecting from one of the moving cars. To enforce that claim he brought an action in the federal court for southern New York, which had jurisdiction because the company is a corporation of that State. It denied liability; and the case was tried by a jury.

The Erie insisted that its duty to Tompkins was no greater than that owed to a trespasser. It contended, among other things, that its duty to Tompkins, and hence its liability, should be determined in accordance with the Pennsylvania law; that under the law of Pennsylvania, as declared by its highest court, persons who use pathways along the railroad right of way—that is a longitudinal pathway as distinguished from a crossing—are to be deemed trespassers; and that the railroad is not liable for injuries to undiscovered trespassers resulting from its negligence, unless it be wanton or wilful. Tompkins denied that any such rule had been established by the decisions of the Pennsylvania courts; and contended that, since there was no statute of the State on the subject, the railroad’s duty and liability is to be determined in federal courts as a matter of general law.

The trial judge refused to rule that the applicable law precluded recovery. The jury brought in a verdict of $30,000; and the judgment entered thereon was affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals, which held that it was unnecessary to consider whether the law of Pennsylvania was as contended, because the question was one not of local, but of general, law and that “upon questions of general law the federal courts are free, in the absence of a local statute, to exercise their independent judgment as to what the law is; and it is well settled that the question of the responsibility of a railroad for injuries caused by its servants is one of general law. … Where the public has made open and notorious use of a railroad right of way for a long period of time and without objection, the company owes to persons on such permissive pathway a duty of care in the operation of its trains. … It is likewise generally recognized law that a jury may find that negligence exists toward a pedestrian using a permissive path on the railroad right of way if he is hit by some object projecting from the side of the train.”

The Erie had contended that application of the Pennsylvania rule was required, among other things, by § 34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789, c. 20, 28 U.S.C. § 725, which provides:

“The laws of the several States, except where the Constitution, treaties, or statutes of the United States otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in trials at common law, in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.”

Because of the importance of the question whether the federal court was free to disregard the alleged rule of the Pennsylvania common law, we granted certiorari.

First. Swift v. Tyson held that federal courts exercising jurisdiction on the ground of diversity of citizenship need not, in matters of general jurisprudence, apply the unwritten law of the State as declared by its highest court; that they are free to exercise an independent judgment as to what the common law of the State is—or should be; and that, as there stated by Mr. Justice Story:

[T]he true interpretation of the [Rules of Decision Act] limited its application to state laws strictly local, that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and titles to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and titles to real estate, and other matters immovable and extraterritorial in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us, that the section did apply, or was intended to apply, to questions of a more general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or local usages of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction of ordinary contracts or other written instruments, and especially to questions of general commercial law, where the state tribunals are called upon to perform the like functions as ourselves, that is, to ascertain upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true exposition of the contract of instrument, or what is the just rule furnished by the principles of commercial law to govern the case.

[…] The federal courts assumed, in the broad field of “general law,” the power to declare rules of decision which Congress was confessedly without power to enact as statutes. Doubt was repeatedly expressed as to the correctness of the construction given [the Act], and as to the soundness of the rule which it introduced. But it was the more recent research of a competent scholar, who examined the original document, which established that the construction given to it by the Court was erroneous; and that the purpose of the section was merely to make certain that, in all matters except those in which some federal law is controlling, the federal courts exercising jurisdiction in diversity of citizenship cases would apply as their rules of decision the law of the State, unwritten as well as written.5

Criticism of the doctrine became widespread after the decision of Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co. There, Brown and Yellow, a Kentucky corporation owned by Kentuckians, and the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, also a Kentucky corporation, wished that the former should have the exclusive privilege of soliciting passenger and baggage transportation at the Bowling Green, Kentucky, railroad station; and that the Black and White, a competing Kentucky corporation, should be prevented from interfering with that privilege. Knowing that such a contract would be void under the common law of Kentucky, it was arranged that the Brown and Yellow reincorporate under the law of Tennessee, and that the contract with the railroad should be executed there. The suit was then brought by the Tennessee corporation in the federal court for Western Kentucky to enjoin competition by the Black and White; an injunction issued by the District Court was sustained by the Court of Appeals; and this Court, citing many decisions in which the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson had been applied, affirmed the decree.

Second. Experience in applying the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson had revealed its defects, political and social; and the benefits expected to flow from the rule did not accrue. Persistence of state courts in their own opinions on questions of common law prevented uniformity; and the impossibility of discovering a satisfactory line of demarcation between the province of general law and that of local law developed a new well of uncertainties.

On the other hand, the mischievous results of the doctrine had become apparent. Diversity of citizenship jurisdiction was conferred in order to prevent apprehended discrimination in State courts against those not citizens of the State. Swift v. Tyson introduced grave discrimination by non-citizens against citizens. It made rights enjoyed under the unwritten “general law” vary according to whether enforcement was sought in the state or in the federal court; and the privilege of selecting the court in which the right should be determined was conferred upon the non-citizen. Thus, the doctrine rendered impossible equal protection of the law. In attempting to promote uniformity of law throughout the United States, the doctrine had prevented uniformity in the administration of the law of the State.

The discrimination resulting became in practice far-reaching. This resulted in part from the broad province accorded to the so-called “general law” as to which federal courts exercised an independent judgment. [The court gave various examples.]

In part the discrimination resulted from the wide range of persons held entitled to avail themselves of the federal rule by resort to the diversity of citizenship jurisdiction. […]

The injustice and confusion incident to the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson have been repeatedly urged as reasons for abolishing or limiting diversity of citizenship jurisdiction. Other legislative relief has been proposed. If only a question of statutory construction were involved, we should not be prepared to abandon a doctrine so widely applied throughout nearly a century. But the unconstitutionality of the course pursued has now been made clear and compels us to do so.

Third. Except in matters governed by the Federal Constitution or by Acts of Congress, the law to be applied in any case is the law of the State. And whether the law of the State shall be declared by its Legislature in a statute or by its highest court in a decision is not a matter of federal concern. There is no federal general common law. Congress has no power to declare substantive rules of common law applicable in a State whether they be local in their nature or “general,” be they commercial law or a part of the law of torts. And no clause in the Constitution purports to confer such a power upon the federal courts. As stated by Mr. Justice Field when protesting in Baltimore & Ohio R.R. Co. v. Baugh against ignoring the Ohio common law of fellow-servant liability:

“[…] [N]otwithstanding the frequency with which the doctrine [of Swift v. Tyson] has been reiterated, there stands, as a perpetual protest against its repetition, the constitution of the United States, which recognizes and preserves the autonomy and independence of the states,—independence in their legislative and independence in their judicial departments. Supervision over either the legislative or the judicial action of the states is in no case permissible except as to matters by the constitution specifically authorized or delegated to the United States. Any interference with either, except as thus permitted, is an invasion of the authority of the state, and, to that extent, a denial of its independence.”

The fallacy underlying the rule declared in Swift v. Tyson is made clear by Mr. Justice Holmes. The doctrine rests upon the assumption that there is “a transcendental body of law outside of any particular State but obligatory within it unless and until changed by statute,” that federal courts have the power to use their judgment as to what the rules of common law are; and that in the federal courts “the parties are entitled to an independent judgment on matters of general law”:

[B]ut law in the sense in which courts speak of it today does not exist without some definite authority behind it. The common law so far as it is enforced in a State, whether called common law or not, is not the common law generally but the law of that State existing by the authority of that State without regard to what it may have been in England or anywhere else. … The authority and only authority is the State, and if that be so, the voice adopted by the State as its own [whether it be of its Legislature or of its Supreme Court] should utter the last word.

Thus the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson is, as Mr. Justice Holmes said, “an unconstitutional assumption of powers by courts of the United States which no lapse of time or respectable array of opinion should make us hesitate to correct.” In disapproving that doctrine we do not hold unconstitutional § 34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 or any other Act of Congress. We merely declare that in applying the doctrine this Court and the lower courts have invaded rights which in our opinion are reserved by the Constitution to the several States.

Fourth. The defendant contended that by the common law of Pennsylvania as declared by its highest court in Falchetti v. Pennsylvania R. Co., the only duty owed to the plaintiff was to refrain from willful or wanton injury. The plaintiff denied that such is the Pennsylvania law. In support of their respective contentions the parties discussed and cited many decisions of the Supreme Court of the State. The Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the question of liability is one of general law; and on that ground declined to decide the issue of state law. As we hold this was error, the judgment is reversed and the case remanded to it for further proceedings in conformity with our opinion.

Reversed.

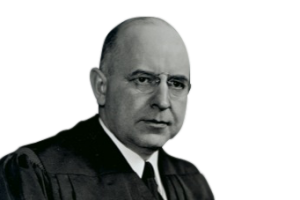

Butler, J.[, concurring]

[…]

Defendant’s petition for writ of certiorari presented two questions: Whether its duty toward plaintiff should have been determined in accordance with the law as found by the highest court of Pennsylvania, and whether the evidence conclusively showed plaintiff guilty of contributory negligence. […]

No constitutional question was suggested or argued below or here. And as a general rule, this Court will not consider any question not raised below and presented by the petition. Here it does not decide either of the questions presented, but, changing the rule of decision in force since the foundation of the government, remands the case to be adjudged according to a standard never before deemed permissible.

[…]

The doctrine of [Swift v. Tyson] has been followed by this Court in an unbroken line of decisions. So far as appears, it was not questioned until more than 50 years later, and then by a single judge. Baltimore & O. Railroad Co. v. Baugh. […]

And since that decision, the division of opinion in this Court has been of the same character as it was before. In 1910, Mr. Justice Holmes, speaking for himself and two other Justices, dissented from the holding that a court of the United States was bound to exercise its own independent judgment in the construction of a conveyance made before the state courts had rendered an authoritative decision as to its meaning and effect. Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Co. […]. But that dissent accepted […] as “settled” the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, and insisted […] merely that the case under consideration was by nature and necessity peculiarly local.

[…]

So far as appears, no litigant has ever challenged the power of Congress to establish the rule as construed. It has so long endured that its destruction now without appropriate deliberation cannot be justified. There is nothing in the opinion to suggest that consideration of any constitutional question is necessary to a decision of the case. […] Against the protest of those joining in this opinion, the Court declines to assign the case for reargument. It may not justly be assumed that the labor and argument of counsel for the parties would not disclose the right conclusion and aid the Court in the statement of reasons to support it. Indeed, it would have been appropriate to give Congress opportunity to be heard before divesting it of power to prescribe rules of decision to be followed in the courts of the United States.

[…]

I am of opinion that the constitutional validity of the rule need not be considered, because under the law, as found by the courts of Pennsylvania and generally throughout the country, it is plain that the evidence required a finding that plaintiff was guilty of negligence that contributed to cause his injuries, and that the judgment below should be reversed upon that ground.

Reed, J.[, concurring]

I concur in the conclusion reached in this case, in the disapproval of the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, and in the reasoning of the majority opinion except insofar as it relies upon the unconstitutionality of the “course pursued” by the federal courts.

[,,,]

To decide the case now before us and to “disapprove” the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson requires only that we say that the words “the laws” [in the Rules of Decision Act] include in their meaning the decisions of the local tribunals. […] [T]his Court is now of the view that “laws” includes “decisions,” [and] it is unnecessary to go further and declare that the “course pursued” was “unconstitutional,” instead of merely erroneous.

The “unconstitutional” course referred to in the majority opinion is apparently the ruling in Swift v. Tyson that the supposed omission of Congress to legislate as to the effect of decisions leaves federal courts free to interpret general law for themselves. I am not at all sure whether, in the absence of federal statutory direction, federal courts would be compelled to follow state decisions. There was sufficient doubt about the matter in 1789 to induce the first Congress to legislate. […] If the opinion commits this Court to the position that the Congress is without power to declare what rules of substantive law shall govern the federal courts, that conclusion also seems questionable. The line between procedural and substantive law is hazy but no one doubts federal power over procedure. The Judiciary Article and the “necessary and proper” clause of Article One may fully authorize legislation, such as this section of the Judiciary Act.

In this Court, stare decisis, in statutory construction, is a useful rule, not an inexorable command. It seems preferable to overturn an established construction of an Act of Congress, rather than, in the circumstances of this case, to interpret the Constitution.

[…]

Notes & Questions

What is the basis for the Court’s holding in Erie: the constitution? The Rules of Decision Act? Both?

Justice Brandeis’s majority opinion in Erie cites an article written by Professor Charles Warren. That article’s major contribution was uncovering a lost draft of the original Rules of Decision Act of 1789. That draft provided: “And be it further enacted, That the Statute law of the several States in force for the time being and their unwritten or common law now in use, whether by adoption from the common law of England, the ancient statutes of the same or otherwise, except where the Constitution, Treaties or Statutes of the United States shall otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in the trials at common law in the courts of the United States in cases where they apply.” What light does this lost draft cast on the final, enacted version of the Rules of Decision Act?

The regime of Swift v. Tyson was premised on the idea that there is a single body of general common law, and that judges deciding common-law cases recognize those general principles rather than making law themselves. In declaring that “there is no federal general common law,” the Erie Court attacked the very notion of general common law. Instead, Erie recognized that the common law can only be law to the extent it is connected to some sovereign power—i.e., state judges. Put differently, Swift was premised on the arguably fictional idea that judges merely “find” law, whereas Erie is premised on the arguably crass suggestion that judges “make” law. Which do you think is the better view of things?

Erie was decided in 1938, the same year that the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure took effect. The late 1930s were a pivotal period in American law, and Erie was a key part of the transformation. But Erie threatened to undermine the newly adopted Rules. If state law supplies the substantive law in diversity cases, does that mean state rules of practice should govern instead of the Federal Rules? As you will see, Erie’s holding is limited to substantive—not procedural—law. But the distinction between substance and procedure is maddeningly vague. To see why, consider the next case, which asks an almost recursive question: which body of law governs the question of which body of law applies to a particular dispute? In other words, does state or federal law dictate the horizontal choice of law inquiry in a diversity case?

Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co

MR. JUSTICE REED delivered the opinion of the Court.

The principal question in this case is whether in diversity cases the federal courts must follow conflict of laws rules prevailing in the states in which they sit. […]

In 1918, respondent, a New York corporation, transferred its entire business to petitioner, a Delaware corporation. Petitioner contracted to use its best efforts to further the manufacture and sale of certain patented devices covered by the agreement, and respondent was to have a share of petitioner’s profits. The agreement was executed in New York, the assets were transferred there, and petitioner began performance there although later it moved its operations to other states. Respondent was voluntarily dissolved under New York law in 1919. Ten years later it instituted this action in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware, alleging that petitioner had failed to perform its agreement to use its best efforts. Jurisdiction rested on diversity of citizenship. In 1939 respondent recovered a jury verdict of $100,000, upon which judgment was entered. Respondent then moved to correct the judgment by adding interest at the rate of six percent from June 1, 1929, the date the action had been brought. The basis of the motion was the provision in § 480 of the New York Civil Practice Act directing that in contract actions interest be added to the principal sum “whether theretofore liquidated or unliquidated.”1 The District Court granted the motion, taking the view that the rights of the parties were governed by New York law and that under New York law the addition of such interest was mandatory. The Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed, and we granted certiorari, limited to the question whether § 480 of the New York Civil Practice Act is applicable to an action in the federal court in Delaware.

“Interest to be included in recovery. Where in any action, except as provided in section four hundred eighty-a, final judgment is rendered for a sum of money awarded by a verdict, report or decision, interest upon the total amount awarded, from the time when the verdict was rendered or the report or decision was made to the time of entering judgment, must be computed by the clerk, added to the total amount awarded, and included in the amount of the judgment. In every action wherein any sum of money shall be awarded by verdict, report or decision upon a cause of action for the enforcement of or based upon breach of performance of a contract, express or implied, interest shall be recovered upon the principal sum whether theretofore liquidated or unliquidated and shall be added to and be a part of the total sum awarded.”

The Circuit Court of Appeals was of the view that under New York law the right to interest before verdict under § 480 went to the substance of the obligation, and that proper construction of the contract in suit fixed New York as the place of performance. It then concluded that § 480 was applicable to the case because “it is clear by what we think is undoubtedly the better view of the law that the rules for ascertaining the measure of damages are not a matter of procedure at all, but are matters of substance which should be settled by reference to the law of the appropriate state according to the type of case being tried in the forum. The measure of damages for breach of a contract is determined by the law of the place of performance; Restatement, Conflict of Laws § 413.” The court referred also to § 418 of the Restatement, which makes interest part of the damages to be determined by the law of the place of performance. Application of the New York statute apparently followed from the court’s independent determination of the “better view” without regard to Delaware law, for no Delaware decision or statute was cited or discussed.

We are of opinion that the prohibition declared in Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, against such independent determinations by the federal courts, extends to the field of conflict of laws. The conflict of laws rules to be applied by the federal court in Delaware must conform to those prevailing in Delaware’s state courts. Otherwise, the accident of diversity of citizenship would constantly disturb equal administration of justice in coordinate state and federal courts sitting side by side. Any other ruling would do violence to the principle of uniformity within a state, upon which the Tompkins decision is based. Whatever lack of uniformity this may produce between federal courts in different states is attributable to our federal system, which leaves to a state, within the limits permitted by the Constitution, the right to pursue local policies diverging from those of its neighbors. It is not for the federal courts to thwart such local policies by enforcing an independent “general law” of conflict of laws. Subject only to review by this Court on any federal question that may arise, Delaware is free to determine whether a given matter is to be governed by the law of the forum or some other law. This Court’s views are not the decisive factor in determining the applicable conflicts rule. And the proper function of the Delaware federal court is to ascertain what the state law is, not what it ought to be.

Besides these general considerations, the traditional treatment of interest in diversity cases brought in the federal courts points to the same conclusion. 28 U.S.C. § 811, relating to interest on judgments, provides that it be calculated from the date of judgment at such rate as is allowed by law on judgments recovered in the courts of the state in which the court is held. […]

Looking then to the Delaware cases, petitioner relies on one group to support his contention that the Delaware state courts would refuse to apply § 480 of the New York Civil Practice Act, and respondent on another to prove the contrary. We make no analysis of these Delaware decisions, but leave this for the Circuit Court of Appeals when the case is remanded.

[…]

Accordingly, the judgment is reversed and the case remanded to the Circuit Court of Appeals for decision in conformity with the law of Delaware.

Reversed.

Notes & Questions

Klaxon held that state choice-of-law rules govern horizontal choice of law in diversity cases.

What test did the Klaxon Court use to determine whether the choice-of-law inquiry should be governed by state or federal law?

The question whether state or federal law should govern proliferated across many areas of the law. The next cases asks which body of law should govern the inquiry about the preclusive effect of a state-court judgment—i.e., res judicata. For more on this topic, see Chapter 8.

Semtek Int’l Inc. v. Lockheed Martin Corp.

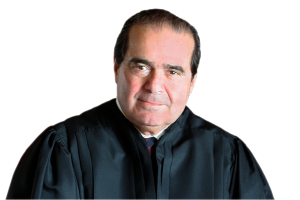

Scalia, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case presents the question whether the claim-preclusive effect of a federal judgment dismissing a diversity action on statute-of-limitations grounds is determined by the law of the State in which the federal court sits.

I

Petitioner filed a complaint against respondent in California state court, alleging breach of contract and various business torts. Respondent removed the case to the United States District Court for the Central District of California on the basis of diversity of citizenship, and successfully moved to dismiss petitioner’s claims as barred by California’s 2-year statute of limitations. In its order of dismissal, the District Court, adopting language suggested by respondent, dismissed petitioner’s claims “in [their] entirety on the merits and with prejudice.” […] Petitioner [then] brought suit against respondent in the State Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland, alleging the same causes of action, which were not time barred under Maryland’s 3-year statute of limitations. […] Following a hearing, the Maryland state court granted respondent’s motion to dismiss on the ground of res judicata. […] The [Maryland] Court of Special Appeals affirmed, holding that, regardless of whether California would have accorded claim-preclusive effect to a statute-of-limitations dismissal by one of its own courts, the dismissal by the California federal court barred the complaint filed in Maryland, since the res judicata effect of federal diversity judgments is prescribed by federal law, under which the earlier dismissal was on the merits and claim preclusive. […]

II

Petitioner contends that the outcome of this case is controlled by Dupasseur v. Rochereau, 88 U.S. 130, 135 (1875), which held that the res judicata effect of a federal diversity judgment “is such as would belong to judgments of the State courts rendered under similar circumstances,” and may not be accorded any “higher sanctity or effect.” Since, petitioner argues, the dismissal of an action on statute-of-limitations grounds by a California state court would not be claim preclusive, it follows that the similar dismissal of this diversity action by the California federal court cannot be claim preclusive. While we agree that this would be the result demanded by Dupasseur, the case is not dispositive because it was decided under the Conformity Act of 1872 [the pre-Rules legislation] which required federal courts to apply the procedural law of the forum State in nonequity cases. […]

Respondent, for its part, contends that the outcome of this case is controlled by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 41(b), which provides as follows:

[Involuntary Dismissal; Effect. If the plaintiff fails to prosecute or to comply with these rules or a court order, a defendant may move to dismiss the action or any claim against it. Unless the dismissal order states otherwise, a dismissal under this subdivision (b) and any dismissal not under this rule—except one for lack of jurisdiction, improper venue, or failure to join a party under Rule 19—operates as an adjudication on the merits.]*

Involuntary Dismissal: Effect Thereof

For failure of the plaintiff to prosecute or to comply with these rules or any order of court, a defendant may move for dismissal of an action or of any claim against the defendant. Unless the court in its order for dismissal otherwise specifies, a dismissal under this subdivision and any dismissal not provided for in this rule, other than a dismissal for lack of jurisdiction, for improper venue, or for failure to join a party under Rule 19, operates as an adjudication upon the merits.

–Ed.

Since the dismissal here did not “[state] otherwise” (indeed, it specifically stated that it was “on the merits”), and did not pertain to the excepted subjects of jurisdiction, venue, or joinder, it follows, respondent contends, that the dismissal “is entitled to claim preclusive effect.”

Implicit in this reasoning is the unstated minor premise that all judgments denominated “on the merits” are entitled to claim-preclusive effect. That premise is not necessarily valid [, because the phrase’s meaning has changed over time]. […]

In short, it is no longer true that a judgment “on the merits” is necessarily a judgment entitled to claim-preclusive effect; and there are a number of reasons for believing that the phrase “adjudication upon the merits” does not bear that meaning in Rule 41(b). […]

And even apart from the purely default character of Rule 41 (b), it would be peculiar to find a rule governing the effect that must be accorded federal judgments by other courts ensconced in rules governing the internal procedures of the rendering court itself. Indeed, such a rule would arguably violate the jurisdictional limitation of the Rules Enabling Act: that the Rules “shall not abridge, enlarge or modify any substantive right,” 28 U.S.C. § 2072(b). […] In the present case, for example, if California law left petitioner free to sue on this claim in Maryland even after the California statute of limitations had expired, the federal court’s extinguishment of that right (through Rule 41(b)’s mandated claim-preclusive effect of its judgment) would seem to violate this limitation.

Moreover, as so interpreted, the Rule would in many cases violate the federalism principle of Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, 78-80 (1938), by engendering “‘substantial’ variations [in outcomes] between state and federal litigation” which would “likely … influence the choice of a forum,” Hanna v. Plumer. See also Guaranty Trust Co. v. York. With regard to the claim-preclusion issue involved in the present case, for example, the traditional rule is that expiration of the applicable statute of limitations merely bars the remedy and does not extinguish the substantive right, so that dismissal on that ground does not have claim-preclusive effect in other jurisdictions with longer, unexpired limitation periods. Out-of-state defendants sued on stale claims in California and in other States adhering to this traditional rule would systematically remove state-law suits brought against them to federal court—where, unless otherwise specified, a statute-of-limitations dismissal would bar suit everywhere.1 We think the key to a more reasonable interpretation of the meaning of “operates as an adjudication upon the merits” in Rule 41(b) is to be found in Rule 41(a)[(1)(B)], which, in discussing the effect of voluntary dismissal by the plaintiff, makes clear that an “adjudication upon the merits” is the opposite of a “dismissal without prejudice”:

[Unless the notice or stipulation states otherwise, the dismissal is without prejudice. But if the plaintiff previously dismissed any federal- or state-court action based on or including the same claim, a notice of dismissal operates as an adjudication on the merits.*

* At the time of the decision, the text of Rule 41(b) read:

“Unless otherwise stated in the notice of dismissal or stipulation, the dismissal is without prejudice, except that a notice of dismissal operates as an adjudication upon the merits when filed by a plaintiff who has once dismissed in any court of the United States or of any state an action based on or including the same claim.”

–Ed.

2 We do not decide whether, in a diversity case, a federal court’s “dismissal upon the merits” (in the sense we have described), under circumstances where a state court would decree only a “dismissal without prejudice,” abridges a “substantive right” and thus exceeds the authorization of the Rules Enabling Act. We think the situation will present itself more rarely than would the arguable violation of the Act that would ensue from interpreting Rule 41(b) as a rule of claim preclusion; and if it is a violation, can be more easily dealt with on direct appeal.

The primary meaning of “dismissal without prejudice,” we think, is dismissal without barring the defendant from returning later, to the same court, with the same underlying claim. That will also ordinarily (though not always) have the consequence of not barring the claim from other courts, but its primary meaning relates to the dismissing court itself. […]

We think, then, that the effect of the “adjudication upon the merits” default provision of Rule 41(b)—and, presumably, of the explicit order in the present case that used the language of that default provision—is simply that, unlike a dismissal “without prejudice,” the dismissal in the present case barred refiling of the same claim in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. That is undoubtedly a necessary condition, but it is not a sufficient one, for claim-preclusive effect in other courts.2

III

Having concluded that the claim-preclusive effect, in Maryland, of this California federal diversity judgment is dictated neither by Dupasseur v. Rochereau, as petitioner contends, nor by Rule 41(b), as respondent contends, we turn to consideration of what determines the issue. Neither the Full Faith and Credit Clause, U.S. Const., Art. IV, §1, nor the full faith and credit statute, 28 U.S.C. §1738, addresses the question. By their terms they govern the effects to be given only to state-court judgments (and, in the case of the statute, to judgments by courts of territories and possessions). And no other federal textual provision, neither of the Constitution nor of any statute, addresses the claim-preclusive effect of a judgment in a federal diversity action.

[…]

It is left to us, then, to determine the appropriate federal rule. And despite the sea change that has occurred in the background law since Dupasseur was decided—not only repeal of the Conformity Act but also the watershed decision of this Court in Erie—we think the result decreed by Dupasseur continues to be correct for diversity cases. Since state, rather than federal, substantive law is at issue there is no need for a uniform federal rule. And indeed, nationwide uniformity in the substance of the matter is better served by having the same claim-preclusive rule (the state rule) apply whether the dismissal has been ordered by a state or a federal court. This is, it seems to us, a classic case for adopting, as the federally prescribed rule of decision, the law that would be applied by state courts in the State in which the federal diversity court sits. See Gasperini v. Ctr. for Humanities, Inc. As we have alluded to above, any other rule would produce the sort of “forum-shopping … and … inequitable administration of the laws” that Erie seeks to avoid, since filing in, or removing to, federal court would be encouraged by the divergent effects that the litigants would anticipate from likely grounds of dismissal. See Guaranty Trust Co. v. York.

This federal reference to state law will not obtain, of course, in situations in which the state law is incompatible with federal interests. If, for example, state law did not accord claim-preclusive effect to dismissals for willful violation of discovery orders, federal courts’ interest in the integrity of their own processes might justify a contrary federal rule. No such conflict with potential federal interests exists in the present case. Dismissal of this state cause of action was decreed by the California federal court only because the California statute of limitations so required; and there is no conceivable federal interest in giving that time bar more effect in other courts than the California courts themselves would impose.

Because the claim-preclusive effect of the California federal court’s dismissal “upon the merits” of petitioner’s action on statute-of-limitations grounds is governed by a federal rule that in turn incorporates California’s law of claim preclusion (the content of which we do not pass upon today), the Maryland Court of Special Appeals erred in holding that the dismissal necessarily precluded the bringing of this action in the Maryland courts. The judgment is reversed, and the case remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

Notes & Questions

Semtek operates at several levels. To understand the case, you must understand each level separately. The first question was which body of law determined the claim-preclusive effect of the California federal court’s judgment. The Court’s answer to that question was “federal common law.” The second question was what rule of claim preclusion existed under federal common law. The Court’s answer was that, as a matter of federal common law, the preclusive effect of a judgment issued by a federal court sitting in diversity is the same as the preclusive effect a state-court judgment would have if it were issued by a state court.

As a result of the foregoing, the Supreme Court remanded a case to Maryland state courts so that they could determine the claim preclusion rules applicable in California state courts, so that they could determine the preclusive effect of the federal-court judgment. Sometimes, federalism can be extremely complicated.

A careful reader will have already recognzied a potential problem. If the source of the claim-preclusion rules applied in Semtek is “federal common law,” how can the outcome in Semtek be squared with Erie, which famously pronounced that “[t]here is no federal general common law.” How does the Semtek Court deal with this problem. Is the kind of common law at issue in Semtek something other than “general”?

14.2 Federal Supremacy

Stewart Org., Inc. v. Ricoh Corp

JUSTICE MARSHALL delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case presents the issue whether a federal court sitting in diversity should apply state or federal law in adjudicating a motion to transfer a case to a venue provided in a contractual forum-selection clause.

I

The dispute underlying this case grew out of a dealership agreement that obligated petitioner company, an Alabama corporation, to market copier products of respondent, a nationwide manufacturer with its principal place of business in New Jersey. The agreement contained a forum-selection clause providing that any dispute arising out of the contract could be brought only in a court located in Manhattan.1 Business relations between the parties soured under circumstances that are not relevant here. In September 1984, petitioner brought a complaint in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama. The core of the complaint was an allegation that respondent had breached the dealership agreement, but petitioner also included claims for breach of warranty, fraud, and antitrust violations.

Relying on the contractual forum-selection clause, respondent moved the District Court either to transfer the case to the Southern District of New York under 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) or to dismiss the case for improper venue under 28 U.S.C. § 1406. The District Court denied the motion. It reasoned that the transfer motion was controlled by Alabama law and that Alabama looks unfavorably upon contractual forum-selection clauses. The court certified its ruling for interlocutory appeal, see 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b), and the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit accepted jurisdiction.

On appeal, a divided panel of the Eleventh Circuit reversed the District Court. The panel concluded that questions of venue in diversity actions are governed by federal law, and that the parties’ forum-selection clause was enforceable as a matter of federal law. The panel therefore reversed the order of the District Court and remanded with instructions to transfer the case to a Manhattan court. After petitioner successfully moved for rehearing en banc, the full Court of Appeals proceeded to adopt the result, and much of the reasoning, of the panel opinion. The en banc court, citing Congress’ enactment or approval of several rules to govern venue determinations in diversity actions, first determined that “[v]enue is a matter of federal procedure.” […] We now affirm under somewhat different reasoning.

II

Both the panel opinion and the opinion of the full Court of Appeals referred to the difficulties that often attend “the sticky question of which law, state or federal, will govern various aspects of the decisions of federal courts sitting in diversity.” A district court’s decision whether to apply a federal statute such as § 1404(a) in a diversity action, however, involves a considerably less intricate analysis than that which governs the “relatively unguided Erie choice.” Hanna v. Plumer. Our cases indicate that when the federal law sought to be applied is a congressional statute, the first and chief question for the district court’s determination is whether the statute is “sufficiently broad to control the issue before the Court.” Walker v. Armco Steel Corp; Burlington Northern R. Co. v. Woods. This question involves a straightforward exercise in statutory interpretation to determine if the statute covers the point in dispute.

If the district court determines that a federal statute covers the point in dispute, it proceeds to inquire whether the statute represents a valid exercise of Congress’ authority under the Constitution. See Hanna v. Plumer. If Congress intended to reach the issue before the district court, and if it enacted its intention into law in a manner that abides with the Constitution, that is the end of the matter; “[f]ederal courts are bound to apply rules enacted by Congress with respect to matters … over which it has legislative power.” Thus, a district court sitting in diversity must apply a federal statute that controls the issue before the court and that represents a valid exercise of Congress’ constitutional powers.

III

Applying the above analysis to this case persuades us that federal law, specifically 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a), governs the parties’ venue dispute.

A

At the outset we underscore a methodological difference in our approach to the question from that taken by the Court of Appeals. The en banc court determined that federal law controlled the issue based on a survey of different statutes and judicial decisions that together revealed a significant federal interest in questions of venue in general, and in choice-of-forum clauses in particular. The Court of Appeals then proceeded to […] determine that the forum-selection clause in this case was enforceable. But the immediate issue before the District Court was whether to grant respondent’s motion to transfer the action under § 1404(a), and as Judge Tjoflat properly noted in his special concurrence below, the immediate issue before the Court of Appeals was whether the District Court’s denial of the § 1404(a) motion constituted an abuse of discretion. […] [T]he first question for consideration should have been whether § 1404(a) itself controls respondent’s request to give effect to the parties’ contractual choice of venue and transfer this case to a Manhattan court. For the reasons that follow, we hold that it does.

B

Section 1404(a) provides: “For the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice, a district court may transfer any civil action to any other district or division where it might have been brought.” Under the analysis outlined above, we first consider whether this provision is sufficiently broad to control the issue before the court. That issue is whether to transfer the case to a court in Manhattan in accordance with the forum-selection clause. We believe that the statute, fairly construed, does cover the point in dispute.

Section 1404(a) is intended to place discretion in the district court to adjudicate motions for transfer according to an “individualized, case-by-case consideration of convenience and fairness.” A motion to transfer under § 1404(a) thus calls on the district court to weigh in the balance a number of case-specific factors. The presence of a forum-selection clause such as the parties entered into in this case will be a significant factor that figures centrally in the district court’s calculus. In its resolution of the § 1404(a) motion in this case, for example, the District Court will be called on to address such issues as the convenience of a Manhattan forum given the parties’ expressed preference for that venue, and the fairness of transfer in light of the forum-selection clause and the parties’ relative bargaining power. The flexible and individualized analysis Congress prescribed in § 1404(a) thus encompasses consideration of the parties’ private expression of their venue preferences.

Section 1404(a) may not be the only potential source of guidance for the District Court to consult in weighing the parties’ private designation of a suitable forum. The premise of the dispute between the parties is that Alabama law may refuse to enforce forum-selection clauses providing for out-of-state venues as a matter of state public policy. If that is so, the District Court will have either to integrate the factor of the forum-selection clause into its weighing of considerations as prescribed by Congress, or else to apply, as it did in this case, Alabama’s categorical policy disfavoring forum-selection clauses. Our cases make clear that, as between these two choices in a single “field of operation,” the instructions of Congress are supreme.

It is true that § 1404(a) and Alabama’s putative policy regarding forum-selection clauses are not perfectly coextensive. Section 1404(a) directs a district court to take account of factors other than those that bear solely on the parties’ private ordering of their affairs. The district court also must weigh in the balance the convenience of the witnesses and those public-interest factors of systemic integrity and fairness that, in addition to private concerns, come under the heading of “the interest of justice.” It is conceivable in a particular case, for example, that because of these factors a district court acting under § 1404(a) would refuse to transfer a case notwithstanding the counterweight of a forum-selection clause, whereas the coordinate state rule might dictate the opposite result. But this potential conflict in fact frames an additional argument for the supremacy of federal law. Congress has directed that multiple considerations govern transfer within the federal court system, and a state policy focusing on a single concern or a subset of the factors identified in § 1404(a) would defeat that command. Its application would impoverish the flexible and multifaceted analysis that Congress intended to govern motions to transfer within the federal system. The forum-selection clause, which represents the parties’ agreement as to the most proper forum, should receive neither dispositive consideration (as respondent might have it) nor no consideration (as Alabama law might have it), but rather the consideration for which Congress provided in § 1404(a). This is thus not a case in which state and federal rules “can exist side by side … each controlling its own intended sphere of coverage without conflict.” Walker.

Because § 1404(a) controls the issue before the District Court, it must be applied if it represents a valid exercise of Congress’ authority under the Constitution. The constitutional authority of Congress to enact § 1404(a) is not subject to serious question. As the Court made plain in Hanna, “the constitutional provision for a federal court system … carries with it congressional power to make rules governing the practice and pleading in those courts, which in turn includes a power to regulate matters which, though falling within the uncertain area between substance and procedure, are rationally capable of classification as either.” Section 1404(a) is doubtless capable of classification as a procedural rule, and indeed, we have so classified it in holding that a transfer pursuant to § 1404(a) does not carry with it a change in the applicable law. It therefore falls comfortably within Congress’ powers under Article III as augmented by the Necessary and Proper Clause.

We hold that federal law, specifically 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a), governs the District Court’s decision whether to give effect to the parties’ forum-selection clause and transfer this case to a court in Manhattan. We therefore affirm the Eleventh Circuit order reversing the District Court’s application of Alabama law. The case is remanded so that the District Court may determine in the first instance the appropriate effect under federal law of the parties’ forum-selection clause on respondent’s § 1404(a) motion.

It is so ordered.

JUSTICE SCALIA, dissenting.

I agree with the opinion of the Court that the initial question before us is whether the validity between the parties of a contractual forum-selection clause falls within the scope of 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a). I cannot agree, however, that the answer to that question is yes. Nor do I believe that the federal courts can, consistent with the twin-aims test of Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, fashion a judge-made rule to govern this issue of contract validity.

I

When a litigant asserts that state law conflicts with a federal procedural statute or formal Rule of Procedure, a court’s first task is to determine whether the disputed point in question in fact falls within the scope of the federal statute or Rule. In this case, the Court must determine whether the scope of § 1404(a) is sufficiently broad to cause a direct collision with state law or implicitly to control the issue before the Court, i.e., validity between the parties of the forum-selection clause, thereby leaving no room for the operation of state law. I conclude that it is not.

Although the language of § 1404(a) provides no clear answer, in my view it does provide direction. The provision vests the district courts with authority to transfer a civil action to another district “[f]or the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice.” This language looks to the present and the future. As the specific reference to convenience of parties and witnesses suggests, it requires consideration of what is likely to be just in the future, when the case is tried, in light of things as they now stand. Accordingly, the courts in applying § 1404(a) have examined a variety of factors, each of which pertains to facts that currently exist or will exist: e.g., the forum actually chosen by the plaintiff, the current convenience of the parties and witnesses, the current location of pertinent books and records, similar litigation pending elsewhere, current docket conditions, and familiarity of the potential courts with governing state law. In holding that the validity between the parties of a forum-selection clause falls within the scope of § 1404(a), the Court inevitably imports, in my view without adequate textual foundation, a new retrospective element into the court’s deliberations, requiring examination of what the facts were concerning, among other things, the bargaining power of the parties and the presence or absence of overreaching at the time the contract was made.

The Court largely attempts to avoid acknowledging the novel scope it gives to § 1404(a) by casting the issue as how much weight a district court should give a forum-selection clause as against other factors when it makes its determination under § 1404(a). I agree that if the weight-among-factors issue were before us, it would be governed by § 1404 (a). That is because, while the parties may decide who between them should bear any inconvenience, only a court can decide how much weight should be given under § 1404(a) to the factor of the parties’ convenience as against other relevant factors such as the convenience of witnesses. But the Court’s description of the issue begs the question: what law governs whether the forum-selection clause is a valid or invalid allocation of any inconvenience between the parties. If it is invalid, i.e., should be voided, between the parties, it cannot be entitled to any weight in the § 1404(a) determination. Since under Alabama law the forum-selection clause should be voided, in this case the question of what weight should be given the forum-selection clause can be reached only if as a preliminary matter federal law controls the issue of the validity of the clause between the parties.

Second, § 1404(a) was enacted against the background that issues of contract, including a contract’s validity, are nearly always governed by state law. It is simply contrary to the practice of our system that such an issue should be wrenched from state control in absence of a clear conflict with federal law or explicit statutory provision. It is particularly instructive in this regard to compare § 1404(a) with another provision, enacted by the same Congress a year earlier, that did preempt state contract law, and in precisely the same field of agreement regarding forum selection. Section 2 of the Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. § 2, provides:

A written provision in … a contract evidencing a transaction involving commerce to settle by arbitration a controversy thereafter arising out of such contract or transaction, or the refusal to perform the whole or any part thereof, or an agreement in writing to submit to arbitration an existing controversy arising out of such a contract, transaction, or refusal, shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.

We have said that an arbitration clause is a “kind of forum-selection clause,” and the contrast between this explicit pre-emption of state contract law on the subject and § 1404(a) could not be more stark. Section 1404(a) is simply a venue provision that nowhere mentions contracts or agreements, much less that the validity of certain contracts or agreements will be matters of federal law. It is difficult to believe that state contract law was meant to be pre-empted by this provision that we have said “should be regarded as a federal judicial housekeeping measure,” that we have said did not change “the relevant factors” which federal courts used to consider under the doctrine of forum non conveniens, and that we have held can be applied retroactively because it is procedural. It seems to me the generality of its language—“[f]or the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice”—is plainly insufficient to work the great change in law asserted here.

Third, it has been common ground in this Court since Erie that when a federal procedural statute or Rule of Procedure is not on point, substantial uniformity of predictable outcome between federal and state courts in adjudicating claims should be striven for. See also Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Mfg. Co. This rests upon a perception of the constitutional and congressional plan underlying the creation of diversity and pendent jurisdiction in the lower federal courts, which should quite obviously be carried forward into our interpretation of ambiguous statutes relating to the exercise of that jurisdiction. We should assume, in other words, when it is fair to do so, that Congress is just as concerned as we have been to avoid significant differences between state and federal courts in adjudicating claims. Thus, in deciding whether a federal procedural statute or Rule of Procedure encompasses a particular issue, a broad reading that would create significant disuniformity between state and federal courts should be avoided if the text permits. See, e.g., Walker; Cohen. As I have shown, the interpretation given § 1404(a) by the Court today is neither the plain nor the more natural meaning; at best, § 1404(a) is ambiguous. I would therefore construe it to avoid the significant encouragement to forum shopping that will inevitably be provided by the interpretation the Court adopts today.

II

Since no federal statute or Rule of Procedure governs the validity of a forum-selection clause, the remaining issue is whether federal courts may fashion a judge-made rule to govern the question. If they may not, the Rules of Decision Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1652, mandates use of state law. See Erie; Hanna v. Plumer (if federal courts lack authority to fashion a rule, “state law must govern because there can be no other law”).

[Justice Scalia concluded that forum-selection clauses raise questions of substance rather than procedure and therefore that state law should govern.]

For the reasons stated, I respectfully dissent.

Notes & Questions

Recall that the gist of the Erie doctrine is that federal courts sitting in diversity apply state substantive law and federal procedural law. Klaxon introduces a wrinkle: because of the constitution’s Supremacy Clause, reproduced in the margin, federal law applies whenever it speaks directly to the question at issue. As a result, if there is a valid federal statute or Rule, it will apply—no matter whether the state law it displaces is procedural or substantive.

Where does Justice Scalia part ways with the majority?

Stewart Organization teaches that an important part of the Erie inquiry is determining whether state and federal law are in conflict with one another. If there is no conflict, then there is often no need to choose between them—both can apply. But in cases of genuine conflict, Erie demands a choice. The cases that follow explore the extent to which state and federal law conflict in greater detail.

14.3 Identifying Conflict

Guaranty Trust Co. v. York

MR. JUSTICE FRANKFURTER delivered the opinion of the Court.

[…]

Th[is] suit, instituted as a class action on behalf of [some of Guaranty’s creditors] and brought in a federal court solely because of diversity of citizenship, is based on an alleged breach of trust by Guaranty in that it failed to protect the interests of the noteholders in [connection with certain corporate transactions]. [Guaranty] moved for summary judgment [on statute of limitations grounds], which was granted […]. On appeal, the Circuit Court of Appeals, one Judge dissenting […] held that in a suit brought on the equity side of a federal district court that court is not required to apply the State statute of limitations that would govern like suits in the courts of a State where the federal court is sitting even though the exclusive basis of federal jurisdiction is diversity of citizenship.

Our starting point must be the policy of federal jurisdiction which Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins embodies. In overruling Swift v. Tyson, Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins did not merely overrule a venerable case. It overruled a particular way of looking at law which dominated the judicial process long after its inadequacies had been laid bare. Law was conceived as a “brooding omnipresence” of Reason, of which decisions were merely evidence and not themselves the controlling formulations. Accordingly, federal courts deemed themselves free to ascertain what Reason, and therefore Law, required wholly independent of authoritatively declared State law, even in cases where a legal right as the basis for relief was created by State authority and could not be created by federal authority and the case got into a federal court merely because it was “between Citizens of different States” under Art. III, § 2 of the Constitution of the United States.

[…]

[…] [T]his case reduces itself to the narrow question whether, when no recovery could be had in a State court because the action is barred by the statute of limitations, a federal court in equity can take cognizance of the suit because there is diversity of citizenship between the parties. Is the outlawry, according to State law, of a claim created by the States a matter of “substantive rights” to be respected by a federal court of equity when that court’s jurisdiction is dependent on the fact that there is a State-created right, or is such statute of “a mere remedial character,” which a federal court may disregard?

[…]

And so the question is not whether a statute of limitations is deemed a matter of “procedure” in some sense. The question is whether such a statute concerns merely the manner and the means by which a right to recover, as recognized by the State, is enforced, or whether such statutory limitation is a matter of substance in the aspect that alone is relevant to our problem, namely, does it significantly affect the result of a litigation for a federal court to disregard a law of a State that would be controlling in an action upon the same claim by the same parties in a State court?

It is therefore immaterial whether statutes of limitation are characterized either as “substantive” or “procedural” in State court opinions in any use of those terms unrelated to the specific issue before us. Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins was not an endeavor to formulate scientific legal terminology. It expressed a policy that touches vitally the proper distribution of judicial power between State and federal courts. In essence, the intent of that decision was to insure that, in all cases where a federal court is exercising jurisdiction solely because of the diversity of citizenship of the parties, the outcome of the litigation in the federal court should be substantially the same, so far as legal rules determine the outcome of a litigation, as it would be if tried in a State court. […]

[…]

[…] The source of substantive rights enforced by a federal court under diversity jurisdiction, it cannot be said too often, is the law of the States. Whenever that law is authoritatively declared by a State, whether its voice be the legislature or its highest court, such law ought to govern in litigation founded on that law, whether the forum of application is a State or a federal court and whether the remedies be sought at law or may be had in equity.

Dicta may be cited characterizing equity as an independent body of law. To the extent that we have indicated, it is. But insofar as these general observations go beyond that, they merely reflect notions that have been replaced by a sharper analysis of what federal courts do when they enforce rights that have no federal origin. And so, before the true source of law that is applied by the federal courts under diversity jurisdiction was fully explored, some things were said that would not now be said. […]

The judgment is reversed and the case is remanded for proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

So ordered.

[The dissenting opinion of Justice Rutledge is omitted.]

Notes & Questions

What test did the York Court apply to determine whether state or federal law governed the statute of limitations?

What did the Court mean when it said that it is “immaterial whether statutes of limitation are characterized either as ‘substantive’ or ‘procedural’”? Isn’t that what the Erie doctrine is all about?

York says that the aim of the Erie doctrine is to ensure that “the outcome of the litigation in the federal court should be substantially the same, so far as legal rules determine the outcome of a litigation, as it would be if tried in a State court.” Is that a fair reading of Erie?

After York was decided, the Supreme Court decided a series of cases that, like York, found many questions to be substantive and therefore governed by state law. See, e.g., Ragan v. Merchants Transfer & Warehouse Co., 337 U.S. 530 (1949) (holding that state law governs the question of when a lawsuit is filed, for statute of limitations purposes); Cohen v. Beneficial Indus. Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541 (1949) (holding that a state law requiring shareholders to post a bond before suing a corporation was substantive for Erie purposes); Woods v. Interstate Realty Co., 337 U.S. 535 (1949) (holding that a state law barring out-of-state corporations who do not pay state taxes from suing in state courts was substantive for Erie purposes); Bernhardt v. Polygraphic Co. of America, 350 U.S. 198 (1956) (holding that state law barring arbitration of employment law matters was substantive for Erie purposes).

In the wake of these aggressive applications of state law, the next case represents a bit of a retreat.

Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Electrical Cooperative

Brennan, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case was brought in the District Court for the Western District of South Carolina. Jurisdiction was based on diversity of citizenship. [Plaintiff], a resident of North Carolina, sued [defendant], a South Carolina corporation, for […] negligence. [The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintff.] […]

[Defendant] is in the business of selling electric power to subscribers in rural sections of South Carolina. [Plaintiff] was employed as a lineman in the construction crew of a construction contractor. The contractor, R. H. Bouligny, Inc., held a contract with the respondent in the amount of $334,300 for the [electrical work]. The petitioner was injured while connecting power lines […].

One of respondent’s affirmative defenses was that, under the South Carolina Workmen’s Compensation Act, [plaintiff]—because the work contracted to be done by his employer was work of the kind also done by the respondent’s own construction and maintenance crews—[qualified as defendant’s employee for purposes of worker’s compensation law. As a result, defendant argued, plaintiff was barred from suing in court and was instead required by state law] to accept statutory compensation benefits as the exclusive remedy for his injuries. […]

II

A question is also presented as to whether on remand the factual issue is to be decided by the judge or by the jury. The respondent argues on the basis of the decision of the Supreme Court of South Carolina in Adams v. Davison-Paxon Co., that the issue of [whether plaintiff was a statutory employee or not] should be decided by the judge and not by the jury. […]

[Defendant] argues that this state-court decision governs the present diversity case and “divests the jury of its normal function” to decide the disputed fact question of [the plaintiff’s status as defendant’s employee]. This is to contend that the federal court is bound under Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins to follow the state court’s holding to secure uniform enforcement of the […] State[’s worker’s compensation scheme].