11 Personal Jurisdiction

11.1 Origins

Personal jurisdiction refers to a court’s ability to assert jurisdiction over a civil defendant. Because of the case that follows, personal jurisdiction is now constitutional in nature. It flows from the due process clauses of the constitution. That makes personal jurisdiction a powerful concept, because a judgment entered without personal jurisdiction is unenforceable in a future suit.

Pennoyer v. Neff concerns two separate lawsuits: one that has already happened, and one that is presently before the court. The earlier lawsuit was an attempt to collect a debt (less than $300) allegedly owed to a lawyer, John Mitchell, by his former client, Marcus Neff. Because Neff was living in another state at the time, he was not afforded personal service of process and instead received only “constructive” notice. When Neff didn’t respond to the suit, Mitchell sought and won a default judgment. After the default judgment was entered, Neff acquired 300 acres of land from the federal government in what is now downtown Portland, Oregon. Mitchell then sought to enforce his default judgment against Neff by asking the sheriff to seize Neff’s land and sell it at auction. Sylvester Pennoyer bought the land and was given a sheriff’s deed to prove his title. Some time later, Neff returned to Oregon and discovered that Pennoyer was in possession of his land.

The second suit, then, was brought by Neff against Pennoyer to recover his 300 acres of property. Each man had a deed to the property: Neff’s was from the federal government; Pennoyer’s was from the sheriff who sold it at auction to satisfy Mitchell’s default judgment against Neff. The court hearing the second suit had to decide who had the superior legal claim to the property.

Pennoyer v. Neff

FIELD, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

This is an action to recover the possession of a tract of land, of the alleged value of $15,000, situated in the State of Oregon. The plaintiff asserts title to the premises by a patent of the United States issued to him in 1866, under the act of Congress of Sept. 27, 1850, usually known as the Donation Law of Oregon. The defendant claims to have acquired the premises under a sheriff’s deed, made upon a sale of the property on execution issued upon a judgment recovered against the plaintiff in one of the circuit courts of the State. The case turns upon the validity of this judgment.

It appears from the record that the judgment was rendered in February, 1866, in favor of J.H. Mitchell, for less than $300, including costs, in an action brought by him upon a demand for services as an attorney; that, at the time the action was commenced and the judgment rendered, the defendant therein, the plaintiff here, was a non-resident of the State that he was not personally served with process, and did not appear therein; and that the judgment was entered upon his default in not answering the complaint, upon a constructive service of summons by publication.

The Code of Oregon provides for [constructive] service when an action is brought against a non-resident and absent defendant, who has property within the State. It also provides, where the action is for the recovery of money or damages, for the attachment of the property of the non-resident. And it also declares that no natural person is subject to the jurisdiction of a court of the State, “unless he appear in the court, or be found within the State, or be a resident thereof, or have property therein; and, in the last case, only to the extent of such property at the time the jurisdiction attached.” Construing this latter provision to mean that, in an action for money or damages where a defendant does not appear in the court, and is not found within the State, and is not a resident thereof, but has property therein, the jurisdiction of the court extends only over such property, the declaration expresses a principle of general, if not universal, law. The authority of every tribunal is necessarily restricted by the territorial limits of the State in which it is established. Any attempt to exercise authority beyond those limits would be deemed in every other forum, as has been said by this court, an illegitimate assumption of power, and be resisted as mere abuse. In the case against the plaintiff, the property here in controversy sold under the judgment rendered was not attached, nor in any way brought under the jurisdiction of the court. Its first connection with the case was caused by a levy of the execution. It was not, therefore, disposed of pursuant to any adjudication, but only in enforcement of a personal judgment, having no relation to the property, rendered against a non-resident without service of process upon him in the action, or his appearance therein. The court below did not consider that an attachment of the property was essential to its jurisdiction or to the validity of the sale, but held that the judgment was invalid from defects in the affidavit upon which the order of publication was obtained, and in the affidavit by which the publication was proved.

There is some difference of opinion among the members of this court as to the rulings [by the court below regarding] these alleged defects. […]

If, therefore, we were confined to the rulings of the court below upon the defects in the affidavits mentioned, we should be unable to uphold its decision. But it was also contended in that court, and is insisted upon here, that the judgment in the State court against the plaintiff was void for want of personal service of process on him, or of his appearance in the action in which it was rendered, and that the premises in controversy could not be subjected to the payment of the demand of a resident creditor except by a proceeding in rem; that is, by a direct proceeding against the property for that purpose. If these positions are sound, the ruling of the Circuit Court as to the invalidity of that judgment must be sustained, notwithstanding our dissent from the reasons upon which it was made. And that they are sound would seem to follow from two well-established principles of public law respecting the jurisdiction of an independent State over persons and property. The several States of the Union are not, it is true, in every respect independent, many of the rights and powers which originally belonged to them being now vested in the government created by the Constitution. But, except as restrained and limited by that instrument, they possess and exercise the authority of independent States, and the principles of public law to which we have referred are applicable to them. One of these principles is, that every State possesses exclusive jurisdiction and sovereignty over persons and property within its territory. As a consequence, every State has the power to determine for itself the civil status and capacities of its inhabitants; to prescribe the subjects upon which they may contract, the forms and solemnities with which their contracts shall be executed, the rights and obligations arising from them, and the mode in which their validity shall be determined and their obligations enforced; and also to regulate the manner and conditions upon which property situated within such territory, both personal and real, may be acquired, enjoyed, and transferred. The other principle of public law referred to follows from the one mentioned; that is, that no State can exercise direct jurisdiction and authority over persons or property without its territory. Story, Confl. Laws, c. 2; Wheat. Int. Law, pt. 2, c. 2. The several States are of equal dignity and authority, and the independence of one implies the exclusion of power from all others. And so it is laid down by jurists, as an elementary principle, that the laws of one State have no operation outside of its territory, except so far as is allowed by comity; and that no tribunal established by it can extend its process beyond that territory so as to subject either persons or property to its decisions. “Any exertion of authority of this sort beyond this limit,” says Story, “is a mere nullity, and incapable of binding such persons or property in any other tribunals.” Story, Confl. Laws, sect. 539.

But as contracts made in one State may be enforceable only in another State, and property may be held by non-residents, the exercise of the jurisdiction which every State is admitted to possess over persons and property within its own territory will often affect persons and property without it. To any influence exerted in this way by a State affecting persons resident or property situated elsewhere, no objection can be justly taken; whilst any direct exertion of authority upon them, in an attempt to give ex-territorial operation to its laws, or to enforce an ex-territorial jurisdiction by its tribunals, would be deemed an encroachment upon the independence of the State in which the persons are domiciled or the property is situated, and be resisted as usurpation.

Thus the State, through its tribunals, may compel persons domiciled within its limits to execute, in pursuance of their contracts respecting property elsewhere situated, instruments in such form and with such solemnities as to transfer the title, so far as such formalities can be complied with; and the exercise of this jurisdiction in no manner interferes with the supreme control over the property by the State within which it is situated.

So the State, through its tribunals, may subject property situated within its limits owned by non-residents to the payment of the demand of its own citizens against them; and the exercise of this jurisdiction in no respect infringes upon the sovereignty of the State where the owners are domiciled. Every State owes protection to its own citizens; and, when non-residents deal with them, it is a legitimate and just exercise of authority to hold and appropriate any property owned by such non-residents to satisfy the claims of its citizens. It is in virtue of the State’s jurisdiction over the property of the non-resident situated within its limits that its tribunals can inquire into that non-resident’s obligations to its own citizens, and the inquiry can then be carried only to the extent necessary to control the disposition of the property. If the non-residents have no property in the State, there is nothing upon which the tribunals can adjudicate.

[…]

[…] If, without personal service, judgments in personam, obtained ex parte against non-residents and absent parties, upon mere publication of process, which, in the great majority of cases, would never be seen by the parties interested, could be upheld and enforced, they would be the constant instruments of fraud and oppression. Judgments for all sorts of claims upon contracts and for torts, real or pretended, would be thus obtained, under which property would be seized, when the evidence of the transactions upon which they were founded, if they ever had any existence, had perished.

Substituted service by publication, or in any other authorized form, may be sufficient to inform parties of the object of proceedings taken where property is once brought under the control of the court by seizure or some equivalent act. The law assumes that property is always in the possession of its owner, in person or by agent; and it proceeds upon the theory that its seizure will inform him, not only that it is taken into the custody of the court, but that he must look to any proceedings authorized by law upon such seizure for its condemnation and sale. Such service may also be sufficient in cases where the object of the action is to reach and dispose of property in the State, or of some interest therein, by enforcing a contract or a lien respecting the same, or to partition it among different owners, or, when the public is a party, to condemn and appropriate it for a public purpose. In other words, such service may answer in all actions which are substantially proceedings in rem. But where the entire object of the action is to determine the personal rights and obligations of the defendants, that is, where the suit is merely in personam, constructive service in this form upon a nonresident is ineffectual for any purpose. Process from the tribunals of one State cannot run into another State, and summon parties there domiciled to leave its territory and respond to proceedings against them. Publication of process or notice within the State where the tribunal sits cannot create any greater obligation upon the non-resident to appear: Process sent to him out of the State, and process published within it, are equally unavailing in proceedings to establish his personal liability.

The want of authority of the tribunals of a State to adjudicate upon the obligations of non-residents, where they have no property within its limits, is not denied by the court below: but the position is assumed, that, where they have property within the State, it is immaterial whether the property is in the first instance brought under the control of the court by attachment or some other equivalent act, and afterwards applied by its judgment to the satisfaction of demands against its owner; or such demands be first established in a personal action, and the property of the non-resident be afterwards seized and sold on execution. But the answer to this position has already been given in the statement, that the jurisdiction of the court to inquire into and determine his obligations at all is only incidental to its jurisdiction over the property. Its jurisdiction in that respect cannot be made to depend upon facts to be ascertained after it has tried the cause and rendered the judgment. If the judgment be previously void, it will not become valid by the subsequent discovery of property of the defendant, or by his subsequent acquisition of it. The judgment, if void when rendered, will always remain void: it cannot occupy the doubtful position of being valid if property be found, and void if there be none. Even if the position assumed were confined to cases where the non-resident defendant possessed property in the State at the commencement of the action, it would still make the validity of the proceedings and judgment depend upon the question whether, before the levy of the execution, the defendant had or had not disposed of the property. If before the levy the property should be sold, then, according to this position, the judgment would not be binding. This doctrine would introduce a new element of uncertainty in judicial proceedings. The contrary is the law: the validity of every judgment depends upon the jurisdiction of the court before it is rendered, not upon what may occur subsequently. In Webster v. Reid, the plaintiff claimed title to land sold under judgments recovered in suits brought in a territorial court of Iowa, upon publication of notice under a law of the territory, without service of process; and the court said:

“These suits were not a proceeding in rem against the land, but were in personam against the owners of it. Whether they all resided within the territory or not does not appear, nor is it a matter of any importance. No person is required to answer in a suit on whom process has not been served, or whose property has not been attached. In this case, there was no personal notice, nor an attachment or other proceeding against the land, until after the judgments. The judgments, therefore, are nullities, and did not authorize the executions on which the land was sold.”

The force and effect of judgments rendered against non-residents without personal service of process upon them, or their voluntary appearance, have been the subject of frequent consideration in the courts of the United States and of the several States, as attempts have been made to enforce such judgments in States other than those in which they were rendered, under the provision of the Constitution requiring that “full faith and credit shall be given in each State to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other State”; and the act of Congress [the current version of which is codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1738] providing for the mode of authenticating such acts, records, and proceedings, and declaring that, when thus authenticated, “they shall have such faith and credit given to them in every court within the United States as they have by law or usage in the courts of the State from which they are or shall be taken.” In the earlier cases, it was supposed that the act gave to all judgments the same effect in other States which they had by law in the State where rendered. But this view was afterwards qualified so as to make the act applicable only when the court rendering the judgment had jurisdiction of the parties and of the subject-matter, and not to preclude an inquiry into the jurisdiction of the court in which the judgment was rendered, or the right of the State itself to exercise authority over the person or the subject-matter. […]

[…]

Since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, the validity of such judgments may be directly questioned, and their enforcement in the State resisted, on the ground that proceedings in a court of justice to determine the personal rights and obligations of parties over whom that court has no jurisdiction do not constitute due process of law. Whatever difficulty may be experienced in giving to those terms a definition which will embrace every permissible exertion of power affecting private rights, and exclude such as is forbidden, there can be no doubt of their meaning when applied to judicial proceedings. They then mean a course of legal proceedings according to those rules and principles which have been established in our systems of jurisprudence for the protection and enforcement of private rights. To give such proceedings any validity, there must be a tribunal competent by its constitution—that is, by the law of its creation—to pass upon the subject-matter of the suit; and, if that involves merely a determination of the personal liability of the defendant, he must be brought within its jurisdiction by service of process within the State, or his voluntary appearance.

Except in cases affecting the personal status of the plaintiff, and cases in which that mode of service may be considered to have been assented to in advance, as hereinafter mentioned, the substituted service of process by publication, allowed by the law of Oregon and by similar laws in other States, where actions are brought against non-residents, is effectual only where, in connection with process against the person for commencing the action, property in the State is brought under the control of the court, and subjected to its disposition by process adapted to that purpose, or where the judgment is sought as a means of reaching such property or affecting some interest therein; in other words, where the action is in the nature of a proceeding in rem. As stated by Cooley in his Treatise on Constitutional Limitations, 405, for any other purpose than to subject the property of a non-resident to valid claims against him in the State, “due process of law would require appearance or personal service before the defendant could be personally bound by any judgment rendered.”

[…]

It follows from the views expressed that the personal judgment recovered in the State court of Oregon against the plaintiff herein, then a non-resident of the State, was without any validity, and did not authorize a sale of the property in controversy.

To prevent any misapplication of the views expressed in this opinion, it is proper to observe that we do not mean to assert, by anything we have said, that a State may not authorize proceedings to determine the status of one of its citizens towards a non-resident, which would be binding within the State, though made without service of process or personal notice to the non-resident. The jurisdiction which every State possesses to determine the civil status and capacities of all its inhabitants involves authority to prescribe the conditions on which proceedings affecting them may be commenced and carried on within its territory. The State, for example, has absolute right to prescribe the conditions upon which the marriage relation between its own citizens shall be created, and the causes for which it may be dissolved. […]

Neither do we mean to assert that a State may not require a non-resident entering into a partnership or association within its limits, or making contracts enforceable there, to appoint an agent or representative in the State to receive service of process and notice in legal proceedings instituted with respect to such partnership, association, or contracts, or to designate a place where such service may be made and notice given, and provide, upon their failure, to make such appointment or to designate such place that service may be made upon a public officer designated for that purpose, or in some other prescribed way, and that judgments rendered upon such service may not be binding upon the nonresidents both within and without the State. […] Nor do we doubt that a State, on creating corporations or other institutions for pecuniary or charitable purposes, may provide a mode in which their conduct may be investigated, their obligations enforced, or their charters revoked, which shall require other than personal service upon their officers or members. Parties becoming members of such corporations or institutions would hold their interest subject to the conditions prescribed by law.

In the present case, there is no feature of this kind, and, consequently, no consideration of what would be the effect of such legislation in enforcing the contract of a non-resident can arise. The question here respects only the validity of a money judgment rendered in one State, in an action upon a simple contract against the resident of another, without service of process upon him, or his appearance therein.

Judgment affirmed.

[The dissenting opinion of Justice HUNT is omitted.]

Notes & Questions

Pennoyer made personal jurisdiction a constitutional limitation on a court’s power derived from the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Those facts remain true today.

Pennoyer’s concept of personal jurisdiction is territorial. The Oregon court’s power extended to people and things within the physical borders of the state—but no farther. This part of Pennoyer, as we will soon see, lasted for more than 70 years, but it is no longer true that personal jurisdiction is so rigidly territorial.

What role, if any, does the due process requirement of notice play in the Court’s discussion of due process? Was the notice afforded to Neff in the first suit constitutionally sufficient?

What would it have taken for the original judgment to be enforceable? Is there anything Mitchell or the earlier court could have done to make sure it had jurisdiction? If so, what?

The Court draws a distinction between two types of personal jurisdiction: in personam and in rem. What is meant by each of those terms?

What exceptions did the Court note to its general territorial theory of personal jurisdiction?

11.2 Long-Arm Statutes

Pennoyer v. Neff constitutionalized personal jurisdiction by making it a requirement of due process. Put differently, Pennoyer held that the Fourteenth Amendment limits state courts’ ability to exercise personal jurisdiction over persons outside the territorial boundaries of the state. You can think of the due process dimension of personal jurisdiction as the maximum that states can exercise under the Constitution.

But states do not have to exercise personal jurisdiction over absent parties to the maximum extent allowed under the Constitution. Instead, states can voluntarily limit the personal jurisdiction of their courts via legislation known as long-arm statutes. In some states, the relevant long-arm statute authorizes state courts to exercise personal jurisdiction to the maximum extent permitted under the Constitution. In other states, including Missouri, the long-arm statute places meaningful limits on personal jurisdiction.

Proper analysis of personal jurisdiction issues thus requires a two-step process. First, you must apply the state’s long-arm statute to determine whether state law authorizes the court to exercise personal jurisdiction over the defendant. If the answer is no, then there is no personal jurisdiction, and the analysis is complete. If personal jurisdiction is authorized by the long-arm statute, however, you must analyze whether it also complies with due process.

This section introduces state long-arm statutes and how to interpret and apply them.

Hess v. Pawloski

Mr. Justice Butler delivered the opinion of the Court.

This action was brought by defendant in error to recover damages for personal injuries. The declaration alleged that plaintiff in error negligently and wantonly drove a motor vehicle on a public highway in Massachusetts and that by reason thereof the vehicle struck and injured defendant in error. Plaintiff in error is a resident of Pennsylvania. No personal service was made on him and no property belonging to him was attached. The service of process was made in compliance with c. 90, General Laws of Massachusetts, as amended by Stat. 1923, c. 431, § 2, the material parts of which follow:

The acceptance by a non-resident of the rights and privileges conferred by section three or four, as evidenced by his operating a motor vehicle thereunder, or the operation by a non-resident of a motor vehicle on a public way in the commonwealth other than under said sections, shall be deemed equivalent to an appointment by such non-resident of the registrar or his successor in office, to be his true and lawful attorney upon whom may be served all lawful processes in any action or proceeding against him, growing out of any accident or collision in which said non-resident may be involved while operating a motor vehicle on such a way, and said acceptance or operation shall be a signification of his agreement that any such process against him which is so served shall be of the same legal force and validity as if served on him personally. Service of such process shall be made by leaving a copy of the process with a fee of two dollars in the hands of the registrar, or in his office, and such service shall be sufficient service upon the said non-resident; provided, that notice of such service “and a copy of the process are forthwith sent by registered mail by the plaintiff to the defendant,” and the defendant’s return receipt and the plaintiff’s affidavit of compliance herewith are appended to the writ and entered with the declaration. The court in which the action is pending may order such continuances as may be necessary to afford the defendant reasonable opportunity to defend the action.

[Defendant] appeared specially for the purpose of contesting jurisdiction and filed an answer in abatement and moved to dismiss on the ground that, the service of process, if sustained, would deprive him of his property without due process of law in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The court overruled the answer in abatement and denied the motion. The Supreme Judicial Court […] affirmed the order. […]

The question is whether the Massachusetts enactment contravenes the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The process of a court of one State cannot run into another and summon a party there domiciled to respond to proceedings against him. Notice sent outside the State to a non-resident is unavailing to give jurisdiction in an action against him personally for money recovery. Pennoyer v. Neff. There must be actual service within the State of notice upon him or upon some one authorized to accept service for him. A personal judgment rendered against a non-resident, who has neither been served with process nor appeared in the suit is without validity. The mere transaction of business in a State by non-resident natural persons does not imply consent to be bound by the process of its courts. The power of a State to exclude foreign corporations, although not absolute but qualified, is the ground on which such an implication is supported as to them. But a State may not withhold from non-resident individuals the right of doing business therein. The privileges and immunities clause of the Constitution, § 2, Art. IV, safeguards to the citizens of one State the right “to pass through, or to reside in any other state for purposes of trade, agriculture, professional pursuits, or otherwise.” And it prohibits state legislation discriminating against citizens of other States.

Motor vehicles are dangerous machines; and, even when skillfully and carefully operated, their use is attended by serious dangers to persons and property. In the public interest the State may make and enforce regulations reasonably calculated to promote care on the part of all, residents and non-residents alike, who use its highways. The measure in question operates to require a non-resident to answer for his conduct in the State where arise causes of action alleged against him, as well as to provide for a claimant a convenient method by which he may sue to enforce his rights. Under the statute the implied consent is limited to proceedings growing out of accidents or collisions on a highway in which the non-resident may be involved. It is required that he shall actually receive and receipt for notice of the service and a copy of the process. And it contemplates such continuances as may be found necessary to give reasonable time and opportunity for defense. It makes no hostile discrimination against non-residents but tends to put them on the same footing as residents. Literal and precise equality in respect of this matter is not attainable; it is not required. The State’s power to regulate the use of its highways extends to their use by non-residents as well as by residents. And, in advance of the operation of a motor vehicle on its highway by a non-resident, the State may require him to appoint one of its officials as his agent on whom process may be served in proceedings growing out of such use. That case recognizes power of the State to exclude a non-resident until the formal appointment is made. And, having the power so to exclude, the State may declare that the use of the highway by the nonresident is the equivalent of the appointment of the registrar as agent on whom process may be served. The difference between the formal and implied appointment is not substantial so far as concerns the application of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Judgment affirmed.

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 506.500

Actions in which outstate service is authorized — jurisdiction of Missouri courts applicable, when. —

Any person or firm, whether or not a citizen or resident of this state, or any corporation, who in person or through an agent does any of the acts enumerated in this section, thereby submits such person, firm, or corporation, and, if an individual, his personal representative, to the jurisdiction of the courts of this state as to any cause of action arising from the doing of any of such acts:

- The transaction of any business within this state;

- The making of any contract within this state;

- The commission of a tortious act within this state;

- The ownership, use, or possession of any real estate situated in this state;

- The contracting to insure any person, property or risk located within this state at the time of contracting;

- Engaging in an act of sexual intercourse within this state with the mother of a child on or near the probable period of conception of that child.

Any person, whether or not a citizen or resident of this state, who has lived in lawful marriage within this state, submits himself to the jurisdiction of the courts of this state as to all civil actions for dissolution of marriage or for legal separation and all obligations arising for maintenance of a spouse, support of any child of the marriage, attorney’s fees, suit money, or disposition of marital property, if the other party to the lawful marriage lives in this state or if a third party has provided support to the spouse or to the children of the marriage and is a resident of this state.

Only causes of action arising from acts enumerated in this section may be asserted against a defendant in an action in which jurisdiction over him is based upon this section.

Missouri ex rel. PPG Indus., Inc. v. McShane

Mary R. Russell, Judge.

PPG Industries, Inc., seeks a writ of prohibition directing the circuit court to dismiss the underlying claim against it for lack of personal jurisdiction. PPG asserts the Circuit Court of St. Louis County cannot exercise personal jurisdiction over it because the underlying claim arises solely out of PPG’s wide-reaching, passive website and does not arise from its contacts with Missouri. This Court issued a preliminary writ of prohibition. Because the circuit court lacks personal jurisdiction over PPG, the preliminary writ is made permanent.

Background

Hilboldt Curtainwall, Inc., a Missouri corporation, agreed to provide building materials for a Missouri-based construction project. Hilboldt, as a subcontractor, was to supply curtainwalls, which included coated aluminum extrusions. The project specifications required the aluminum extrusions be coated with a product made by PPG, a Pennsylvania-based corporation, or an approved substitute. Hilboldt alleges that after seeing on PPG’s website that Finishing Dynamics, LLC, was an “approved” applicator of the required coating, it contracted with Finishing Dynamics to apply the coating.

When Finishing Dynamics failed to properly coat the aluminum extrusions, rendering them defective and unusable in the construction project, Hilboldt sued PPG and Finishing Dynamics. The count against PPG was for negligent misrepresentation based on PPG’s online representation that Finishing Dynamics was an “approved extrusion applicator.” PPG filed a motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction, arguing its website was insufficient to render it subject to the state’s personal jurisdiction. After the circuit court overruled PPG’s motion to dismiss, PPG filed a petition for a writ of prohibition in this Court seeking to prevent the circuit court from taking any further action in the case other than dismissing the claim against it. This Court issued a preliminary writ of prohibition.

Standard of Review

The Missouri Constitution vests this Court with the authority to issue and determine original remedial writs. Mo. Const. art. V, sec. 4. Prohibition is a discretionary writ that will only issue to (1) prevent a court from acting in excess of its authority or jurisdiction; (2) remedy a court acting in excess of its authority or jurisdiction or abusing its discretion; or (3) avoid irreparable harm to a party. “Prohibition is the proper remedy to prevent further action of the trial court where personal jurisdiction of the defendant is lacking.”

Analysis

The question before this Court is whether the circuit court erred in overruling PPG’s motion to dismiss and finding the circuit court had personal jurisdiction over PPG. Hilboldt asserts the circuit court has personal jurisdiction under section 506.500, Missouri’s long-arm statute, because PPG committed a tortious act—negligent misrepresentation—in Missouri. PPG argues Hilboldt failed to establish the circuit court has personal jurisdiction in that PPG is a Pennsylvania-based corporation and its only ties to Missouri in the instant case were the representations made on its passive website, which were not aimed specifically at Missouri consumers. To answer this question, a brief review of the concepts of personal jurisdiction is helpful.

[…]

Missouri courts use a two-prong test to determine if personal jurisdiction exists over a nonresident defendant. First, the out-of-state defendant’s conduct “must fall within Missouri’s long-arm statute, section 506.600.” Once it has been determined the nonresident defendant’s conduct is covered under the long-arm statute, the court must then determine whether the defendant has sufficient minimum contacts with Missouri to satisfy due process.

Missouri’s long-arm statute provides:

Any person or firm, whether or not a citizen or resident of this state, or any corporation, who in person or through an agent does any of the acts enumerated in this section, thereby submits such person, firm, or corporation, and, if an individual, his personal representative, to the jurisdiction of the courts of this state as to any cause of action arising from the doing of any of such acts: […]

(3) The commission of a tortious act within the state.

Section 506.500.1(3).

Included in the tortious act section of the long-arm statute are “[e]xtraterritorial acts that produce consequences in the state, such as fraud.” Hilboldt concedes PPG’s conduct was extraterritorial but nevertheless argues the circuit court has jurisdiction over PPG because “PPG’s misrepresentations … were received by Hilboldt in Missouri, relied upon by Hilboldt in Missouri, and … caused injury to Hilboldt in Missouri.” Hilboldt contends these “consequences in the state” are sufficient to find PPG committed a tortious act in Missouri.

Hilboldt principally relies on Bryant [v. Smith Interior Design Grp., Inc., 310 S.W.3d 227, 232 (Mo. 2010)] to further its argument that PPG acted tortiously within Missouri. In Bryant, an out-of-state defendant sent allegedly fraudulent documents to a Missouri resident and concealed its fraud in subsequent communications with that resident over telephone, email, and written correspondence. The allegations of directed action into the state of Missouri were “sufficient to demonstrate the commission of a tortious act within this state and to place [the defendant] within the reach of Missouri’s long-arm statute.” “Where a defendant knowingly sends into a state a false statement, intended that it should there be relied upon to the injury of a resident of that state, he has, for jurisdictional purposes, acted within that state.”

Bryant is distinguishable on its facts. In Bryant, the defendant sent physical mail and emails and made phone calls directly to the Missouri plaintiff. Here, no such direct or individual communication was made to Hilboldt. PPG did not contact any Hilboldt representative through its website, nor did Hilboldt interact with any PPG representative using the website. The website was not used to complete any transaction, facilitate any communication, or beget any interaction between Hilboldt and PPG. And although the website was accessible by Missouri residents, it was not targeted at Missouri residents. PPG sent nothing into Missouri, nor did it attempt to solicit web traffic from Missouri specifically. PPG did nothing more than publish information that was equally as available to individuals in each of the other 49 states as it was to residents of Missouri.

The absolute remoteness of the connection between PPG’s online representation and the forum state bears emphasizing. PPG merely indicated on its website that Finishing Dynamics was one of an indeterminate number of companies it had deemed “approved extrusion applicator[s].” This wide-reaching, public posting of information was the extent of PPG’s “action” at issue here. Given the broad and general nature of PPG’s website, PPG’s suit-related contacts with Missouri are not sufficient to be considered tortious acts within the state.4

Additionally, the information on PPG’s website that Hilboldt allegedly relied upon was used to enter into a contract with a third party, Finishing Dynamics—a contract in which PPG had no role. And it was this third party’s alleged unilateral mistake that is the true basis for the underlying lawsuit, which muddles the connection between PPG and Missouri even further. Without more, the website’s accessibility in Missouri is insufficient to confer personal jurisdiction.

The mere allegation that a website, accessible by internet users in every state in the country, published false or misleading statements cannot be enough to conclude the website owner acted tortiously within Missouri. To find specific jurisdiction under these facts would allow PPG—and virtually any other company with a website—to be sued in Missouri if its website was viewed by a party who believes it was aggrieved by the information obtained. Such a result would open up Missouri courts to suits against companies who lack even negligible contacts with the state. […] This cannot be the proper result. […]

PPG’s connection to Missouri, based solely on its passive internet activity, is so very attenuated and so very remote that any consequences felt in Missouri in this case cannot reasonably be attributed to PPG’s online activity. Because PPG’s conduct does not fall within Missouri’s long-arm statute, Hilboldt cannot demonstrate its claim satisfies the first prong of the test for personal jurisdiction.6 As such, the circuit court does not have personal jurisdiction over PPG.

Conclusion

Because there was no tortious act within the state, the circuit court lacks personal jurisdiction over PPG. The circuit court should have sustained PPG’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction. The preliminary writ of prohibition is made permanent, and the circuit court is directed to dismiss the underlying claim against PPG. All concur.

11.3 Minimum Contacts

Technological, economic, and social change put tremendous pressure on the territorial models of personal jurisdiction, as Hess illustrates. One of the most important challenges as the Pennoyer model began to break down was the question of where, exactly, a corporation was “present” for purposes of personal jurisdiction. In light of this uncertainty, corporations ordered their behavior so that they could do business in a jurisdiction without being subject to suit there. The next case, which set the agenda for the next 80 years (and counting), resolved that problem by reorienting personal jurisdiction around a defendant’s contacts with the forum.

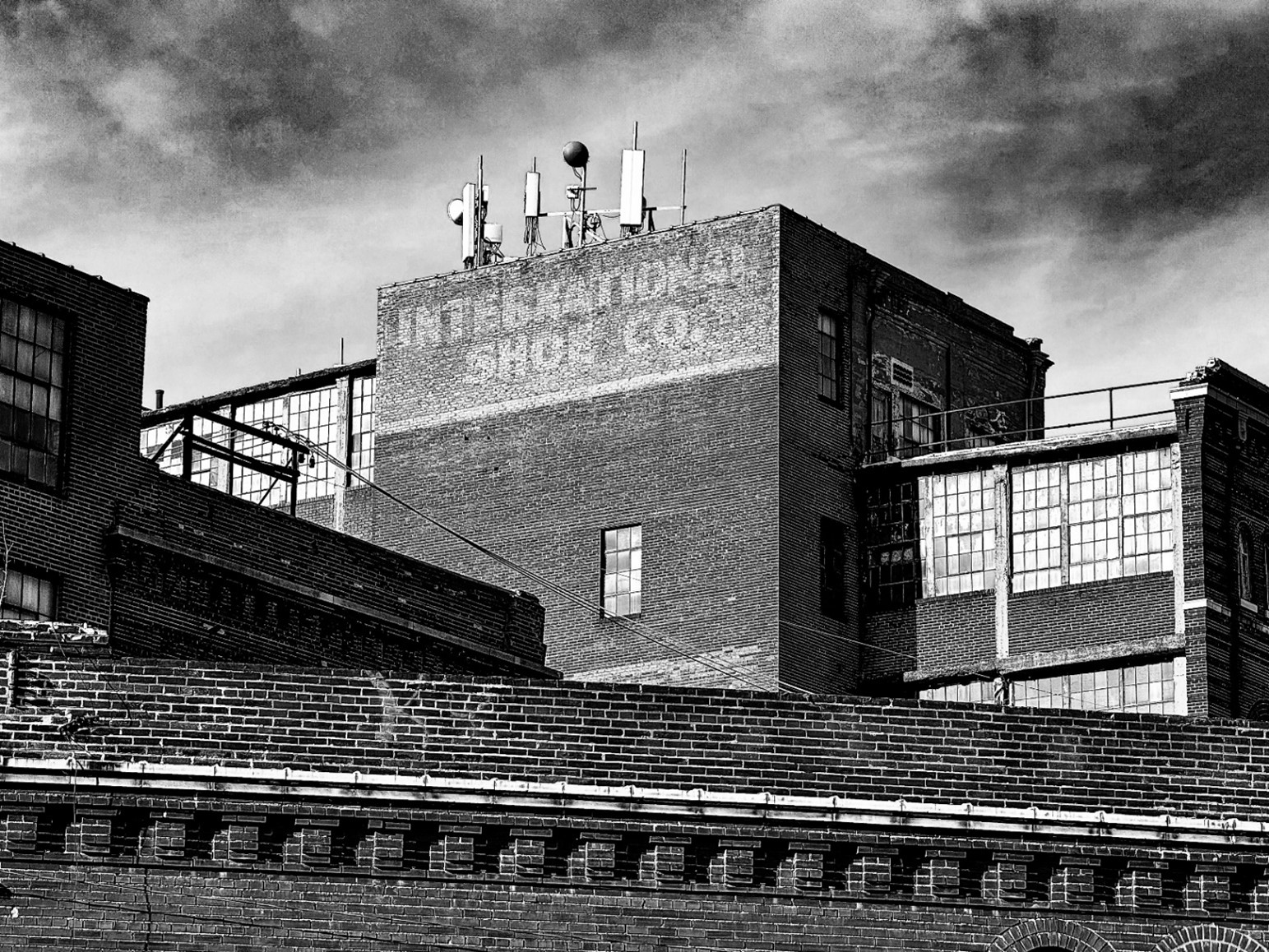

International Shoe Co. v. Washington

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE STONE delivered the opinion of the Court.

The questions for decision are (1) whether, within the limitations of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the appellant, a Delaware corporation, has by its activities in the State of Washington rendered itself amenable to proceedings in the courts of that state to recover unpaid contributions to the state unemployment compensation fund enacted by state statutes, Washington Unemployment Compensation Act, and (2) whether the state can exact those contributions consistently with the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The statutes in question set up a comprehensive scheme of unemployment compensation, the costs of which are defrayed by contributions required to be made by employers to a state unemployment compensation fund. The contributions are a specified percentage of the wages payable annually by each employer for his employees’ services in the state. The assessment and collection of the contributions and the fund are administered by appellees. Section 14(c) of the Act authorizes appellee Commissioner to issue an order and notice of assessment of delinquent contributions upon prescribed personal service of the notice upon the employer if found within the state, or, if not so found, by mailing the notice to the employer by registered mail at his last known address. […]

In this case notice of assessment for the years in question was personally served upon a sales solicitor employed by appellant in the State of Washington, and a copy of the notice was mailed by registered mail to appellant at its address in St. Louis, Missouri. Appellant appeared specially before the office of unemployment and moved to set aside the order and notice of assessment on the ground that the service upon appellant’s salesman was not proper service upon appellant; that appellant was not a corporation of the State of Washington and was not doing business within the state; that it had no agent within the state upon whom service could be made; and that appellant is not an employer and does not furnish employment within the meaning of the statute.

[…]

The facts as found by the appeal tribunal and accepted by the state Superior Court and Supreme Court, are not in dispute. Appellant is a Delaware corporation, having its principal place of business in St. Louis, Missouri, and is engaged in the manufacture and sale of shoes and other footwear. It maintains places of business in several states, other than Washington, at which its manufacturing is carried on and from which its merchandise is distributed interstate through several sales units or branches located outside the State of Washington.

Appellant has no office in Washington and makes no contracts either for sale or purchase of merchandise there. It maintains no stock of merchandise in that state and makes there no deliveries of goods in intrastate commerce. During the years from 1937 to 1940, now in question, appellant employed eleven to thirteen salesmen under direct supervision and control of sales managers located in St. Louis. These salesmen resided in Washington; their principal activities were confined to that state; and they were compensated by commissions based upon the amount of their sales. The commissions for each year totaled more than $31,000. Appellant supplies its salesmen with a line of samples, each consisting of one shoe of a pair, which they display to prospective purchasers. On occasion they rent permanent sample rooms, for exhibiting samples, in business buildings, or rent rooms in hotels or business buildings temporarily for that purpose. The cost of such rentals is reimbursed by appellant. The authority of the salesmen is limited to exhibiting their samples and soliciting orders from prospective buyers, at prices and on terms fixed by appellant. The salesmen transmit the orders to appellant’s office in St. Louis for acceptance or rejection, and when accepted the merchandise for filling the orders is shipped f.o.b. from points outside Washington to the purchasers within the state. All the merchandise shipped into Washington is invoiced at the place of shipment from which collections are made. No salesman has authority to enter into contracts or to make collections.

[…]

Appellant […] insists that its activities within the state were not sufficient to manifest its “presence” there and that in its absence the state courts were without jurisdiction, that consequently it was a denial of due process for the state to subject appellant to suit. […] And appellant further argues that since it was not present within the state, it is a denial of due process to subject it to taxation or other money exaction. It thus denies the power of the state to lay the tax or to subject appellant to a suit for its collection.

Historically the jurisdiction of courts to render judgment in personam is grounded on their de facto power over the defendant’s person. Hence his presence within the territorial jurisdiction of a court was prerequisite to its rendition of a judgment personally binding him. Pennoyer v. Neff. But now that the capias ad respondendum* has given way to personal service of summons or other form of notice, due process requires only that in order to subject a defendant to a judgment in personam, if he be not present within the territory of the forum, he have certain minimum contacts with it such that the maintenance of the suit does not offend “traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.” Milliken v. Meyer. See Hess v. Pawkloski.

Since the corporate personality is a fiction, although a fiction intended to be acted upon as though it were a fact, it is clear that unlike an individual its “presence” without, as well as within, the state of its origin can be manifested only by activities carried on in its behalf by those who are authorized to act for it. To say that the corporation is so far “present” there as to satisfy due process requirements, for purposes of taxation or the maintenance of suits against it in the courts of the state, is to beg the question to be decided. For the terms “present” or “presence” are used merely to symbolize those activities of the corporation’s agent within the state which courts will deem to be sufficient to satisfy the demands of due process. Those demands may be met by such contacts of the corporation with the state of the forum as to make it reasonable, in the context of our federal system of government, to require the corporation to defend the particular suit which is brought there. An “estimate of the inconveniences” which would result to the corporation from a trial away from its “home” or principal place of business is relevant in this connection.

“Presence” in the state in this sense has never been doubted when the activities of the corporation there have not only been continuous and systematic, but also give rise to the liabilities sued on, even though no consent to be sued or authorization to an agent to accept service of process has been given. Conversely it has been generally recognized that the casual presence of the corporate agent or even his conduct of single or isolated items of activities in a state in the corporation’s behalf are not enough to subject it to suit on causes of action unconnected with the activities there. To require the corporation in such circumstances to defend the suit away from its home or other jurisdiction where it carries on more substantial activities has been thought to lay too great and unreasonable a burden on the corporation to comport with due process.

While it has been held, in cases on which appellant relies, that continuous activity of some sorts within a state is not enough to support the demand that the corporation be amenable to suits unrelated to that activity, there have been instances in which the continuous corporate operations within a state were thought so substantial and of such a nature as to justify suit against it on causes of action arising from dealings entirely distinct from those activities.

Finally, although the commission of some single or occasional acts of the corporate agent in a state sufficient to impose an obligation or liability on the corporation has not been thought to confer upon the state authority to enforce it, other such acts, because of their nature and quality and the circumstances of their commission, may be deemed sufficient to render the corporation liable to suit. True, some of the decisions holding the corporation amenable to suit have been supported by resort to the legal fiction that it has given its consent to service and suit, consent being implied from its presence in the state through the acts of its authorized agents. But more realistically it may be said that those authorized acts were of such a nature as to justify the fiction.

It is evident that the criteria by which we mark the boundary line between those activities which justify the subjection of a corporation to suit, and those which do not, cannot be simply mechanical or quantitative. The test is not merely, as has sometimes been suggested, whether the activity, which the corporation has seen fit to procure through its agents in another state, is a little more or a little less. Whether due process is satisfied must depend rather upon the quality and nature of the activity in relation to the fair and orderly administration of the laws which it was the purpose of the due process clause to insure. That clause does not contemplate that a state may make binding a judgment in personam against an individual or corporate defendant with which the state has no contacts, ties, or relations.

But to the extent that a corporation exercises the privilege of conducting activities within a state, it enjoys the benefits and protection of the laws of that state. The exercise of that privilege may give rise to obligations, and, so far as those obligations arise out of or are connected with the activities within the state, a procedure which requires the corporation to respond to a suit brought to enforce them can, in most instances, hardly be said to be undue.

Applying these standards, the activities carried on in behalf of appellant in the State of Washington were neither irregular nor casual. They were systematic and continuous throughout the years in question. They resulted in a large volume of interstate business, in the course of which appellant received the benefits and protection of the laws of the state, including the right to resort to the courts for the enforcement of its rights. The obligation which is here sued upon arose out of those very activities. It is evident that these operations establish sufficient contacts or ties with the state of the forum to make it reasonable and just, according to our traditional conception of fair play and substantial justice, to permit the state to enforce the obligations which appellant has incurred there. Hence we cannot say that the maintenance of the present suit in the State of Washington involves an unreasonable or undue procedure.

We are likewise unable to conclude that the service of the process within the state upon an agent whose activities establish appellant’s “presence” there was not sufficient notice of the suit, or that the suit was so unrelated to those activities as to make the agent an inappropriate vehicle for communicating the notice. It is enough that appellant has established such contacts with the state that the particular form of substituted service adopted there gives reasonable assurance that the notice will be actual. Nor can we say that the mailing of the notice of suit to appellant by registered mail at its home office was not reasonably calculated to apprise appellant of the suit.

[…]

Appellant having rendered itself amenable to suit upon obligations arising out of the activities of its salesmen in Washington, the state may maintain the present suit in personam to collect the tax laid upon the exercise of the privilege of employing appellant’s salesmen within the state. For Washington has made one of those activities, which taken together establish appellant’s “presence” there for purposes of suit, the taxable event by which the state brings appellant within the reach of its taxing power. The state thus has constitutional power to lay the tax and to subject appellant to a suit to recover it. The activities which establish its “presence” subject it alike to taxation by the state and to suit to recover the tax.

Affirmed.

MR. JUSTICE BLACK delivered the following opinion.

[…]

I believe that the Federal Constitution leaves to each State, without any “ifs” or “buts,” a power to tax and to open the doors of its courts for its citizens to sue corporations whose agents do business in those States. Believing that the Constitution gave the States that power, I think it a judicial deprivation to condition its exercise upon this Court’s notion of “fair play,” however appealing that term may be. Nor can I stretch the meaning of due process so far as to authorize this Court to deprive a State of the right to afford judicial protection to its citizens on the ground that it would be more “convenient” for the corporation to be sued somewhere else.

There is a strong emotional appeal in the words “fair play” “justice,” and “reasonableness.” But they were not chosen by those who wrote the original Constitution or the Fourteenth Amendment as a measuring rod for this Court to use in invalidating State or Federal laws passed by elected legislative representatives. No one, not even those who most feared a democratic government, ever formally proposed that courts should be given power to invalidate legislation under any such elastic standards. […]

True, the State’s power is here upheld. But the rule announced means that tomorrow’s judgment may strike down a State or Federal enactment on the ground that it does not conform to the Court’s idea of natural justice. […]

Notes & Questions

Why did the International Shoe Company have so many unusual policies? For example, sales personnel were given only one of each shoe to take with them for display purposes. And they were given no authority to enter into sales contracts directly. Instead, contracts were finalized and orders were fulfilled and shipped from ISC’s warehouse in Missouri “f.o.b.” (What does “f.o.b.” mean?) Why would the company take all of these steps?

Which inquiry is easier? Figuring out where a corporation is “present” or figuring out where it has contacts and how many contacts are enough to satisfy due process? Why? Does the constitution provide any guidance on which one is required?

The major question after International Shoe was decided was whether any portion of Pennoyer survived the revolutionary transformation from territorial jurisdiction to minimum contacts. The next two cases explore the vitality of two types of service that had traditionally been recognized under the Pennoyer regime but were arguably inconsistent with the minimum contacts approach ushered in by International Shoe.

Shaffer v. Heitner

MARSHALL, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

The controversy in this case concerns the constitutionality of a Delaware statute that allows a court of that State to take jurisdiction of a lawsuit by sequestering any property of the defendant that happens to be located in Delaware. Appellants contend that the sequestration statute as applied in this case violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment both because it permits the state courts to exercise jurisdiction despite the absence of sufficient contacts among the defendants, the litigation, and the State of Delaware and because it authorizes the deprivation of defendants’ property without providing adequate procedural safeguards. We find it necessary to consider only the first of these contentions.

I

Appellee Heitner, a nonresident of Delaware, is the owner of one share of stock in the Greyhound Corporation, a business incorporated under the laws of Delaware with its principal place of business in Phoenix, Ariz. On May 22, 1974, he filed a shareholder’s derivative suit in the Court of Chancery for New Castle County, Del., in which he named as defendants Greyhound, its wholly owned subsidiary Greyhound Lines, Inc., and 28 present or former officers or directors of one or both of the corporations. In essence, Heitner alleged that the individual defendants had violated their duties to Greyhound by causing it and its subsidiary to engage in actions that resulted in the corporation’s being held liable for substantial damages in a private antitrust suit and a large fine in a criminal contempt action. The activities which led to these penalties took place in Oregon.

Simultaneously with his complaint, Heitner filed a motion for an order of sequestration of the Delaware property of the individual defendants pursuant to 10 Del. C. § 366. This motion was accompanied by a supporting affidavit of counsel which stated that the individual defendants were nonresidents of Delaware. The affidavit identified the property to be sequestered as

common stock, 3% Second Cumulative Preferenced Stock and stock unit credits of the Defendant Greyhound Corporation, a Delaware corporation, as well as all options and all warrants to purchase said stock issued to said individual Defendants and all contractral [sic] obligations, all rights, debts or credits due or accrued to or for the benefit of any of the said Defendants under any type of written agreement, contract, or other legal instrument of any kind whatever between any of the individual Defendants and said corporation.

The requested sequestration order was signed the day the motion was filed. Pursuant to that order, the sequestrator “seized” approximately 82,000 shares of Greyhound common stock belonging to 19 of the defendants, and options belonging to another two defendants. These seizures were accomplished by placing “stop transfer” orders or their equivalents on the books of the Greyhound Corporation. So far as the record shows, none of the certificates representing the seized property was physically present in Delaware. The stock was considered to be in Delaware, and so subject to seizure, by virtue of 8 Del. C. § 169, which makes Delaware the situs of ownership of all stock in Delaware corporations.

All 28 defendants were notified of the initiation of the suit by certified mail directed to their last known addresses and by publication in a New Castle County newspaper. The 21 defendants whose property was seized (hereafter referred to as appellants) responded by entering a special appearance for the purpose of moving to quash service of process and to vacate the sequestration order. They contended that the ex parte sequestration procedure did not accord them due process of law and that the property seized was not capable of attachment in Delaware. In addition, appellants asserted that under the rule of International Shoe Co. v. Washington, they did not have sufficient contacts with Delaware to sustain the jurisdiction of that State’s courts.

[…]

II

The Delaware courts rejected appellants’ jurisdictional challenge by noting that this suit was brought as a quasi in rem proceeding. Since quasi in rem jurisdiction is traditionally based on attachment or seizure of property present in the jurisdiction, not on contacts between the defendant and the State, the courts considered appellants’ claimed lack of contacts with Delaware to be unimportant. This categorical analysis assumes the continued soundness of the conceptual structure founded on the century-old case of Pennoyer v. Neff.

[The Court reviewed Pennoyer and its rationale.]

From our perspective, the importance of Pennoyer is not its result, but the fact that its principles and corollaries derived from them became the basic elements of the constitutional doctrine governing state-court jurisdiction. As we have noted, under Pennoyer state authority to adjudicate was based on the jurisdiction’s power over either persons or property. This fundamental concept is embodied in the very vocabulary which we use to describe judgments. If a court’s jurisdiction is based on its authority over the defendant’s person, the action and judgment are denominated “in personam” and can impose a personal obligation on the defendant in favor of the plaintiff. If jurisdiction is based on the court’s power over property within its territory, the action is called “in rem” or “quasi in rem.” The effect of a judgment in such a case is limited to the property that supports jurisdiction and does not impose a personal liability on the property owner, since he is not before the court. In Pennoyer’s terms, the owner is affected only “indirectly” by an in rem judgment adverse to his interest in the property subject to the court’s disposition.

By concluding that “[t]he authority of every tribunal is necessarily restricted by the territorial limits of the State in which it is established,” Pennoyer sharply limited the availability of in personam jurisdiction over defendants not resident in the forum State. If a nonresident defendant could not be found in a State, he could not be sued there. On the other hand, since the State in which property was located was considered to have exclusive sovereignty over that property, in rem actions could proceed regardless of the owner’s location. Indeed, since a State’s process could not reach beyond its borders, this Court held after Pennoyer that due process did not require any effort to give a property owner personal notice that his property was involved in an in rem proceeding.

The Pennoyer rules generally favored nonresident defendants by making them harder to sue. This advantage was reduced, however, by the ability of a resident plaintiff to satisfy a claim against a nonresident defendant by bringing into court any property of the defendant located in the plaintiff’s State. For example, in the well-known case of Harris v. Balk, Epstein, a resident of Maryland, had a claim against Balk, a resident of North Carolina. Harris, another North Carolina resident, owed money to Balk. When Harris happened to visit Maryland, Epstein garnished his debt to Balk. Harris did not contest the debt to Balk and paid it to Epstein’s North Carolina attorney. When Balk later sued Harris in North Carolina, this Court held that the Full Faith and Credit Clause, U.S. Const., Art. IV, § 1, required that Harris’ payment to Epstein be treated as a discharge of his debt to Balk. This Court reasoned that the debt Harris owed Balk was an intangible form of property belonging to Balk, and that the location of that property traveled with the debtor. By obtaining personal jurisdiction over Harris, Epstein had “arrested” his debt to Balk, and brought it into the Maryland court. Under the structure established by Pennoyer, Epstein was then entitled to proceed against that debt to vindicate his claim against Balk, even though Balk himself was not subject to the jurisdiction of a Maryland tribunal.

Pennoyer itself recognized that its rigid categories, even as blurred by the kind of action typified by Harris, could not accommodate some necessary litigation. Accordingly, Mr. Justice Field’s opinion carefully noted that cases involving the personal status of the plaintiff, such as divorce actions, could be adjudicated in the plaintiff’s home State even though the defendant could not be served within that State. Similarly, the opinion approved the practice of considering a foreign corporation doing business in a State to have consented to being sued in that State. This basis for in personam jurisdiction over foreign corporations was later supplemented by the doctrine that a corporation doing business in a State could be deemed “present” in the State, and so subject to service of process under the rule of Pennoyer.

The advent of automobiles, with the concomitant increase in the incidence of individuals causing injury in States where they were not subject to in personam actions under Pennoyer, required further moderation of the territorial limits on jurisdictional power. This modification, like the accommodation to the realities of interstate corporate activities, was accomplished by use of a legal fiction that left the conceptual structure established in Pennoyer theoretically unaltered. The fiction used was that the out-of-state motorist, who it was assumed could be excluded altogether from the State’s highways, had by using those highways appointed a designated state official as his agent to accept process. See Hess v. Pawloski. Since the motorist’s “agent” could be personally served within the State, the state courts could obtain in personam jurisdiction over the nonresident driver.

The motorists’ consent theory was easy to administer since it required only a finding that the out-of-state driver had used the State’s roads. By contrast, both the fictions of implied consent to service on the part of a foreign corporation and of corporate presence required a finding that the corporation was “doing business” in the forum State. Defining the criteria for making that finding and deciding whether they were met absorbed much judicial energy. While the essentially quantitative tests which emerged from these cases purported simply to identify circumstances under which presence or consent could be attributed to the corporation, it became clear that they were in fact attempting to ascertain “what dealings make it just to subject a foreign corporation to local suit.” In International Shoe, we acknowledged that fact.

[…]

It is clear, therefore, that the law of state-court jurisdiction no longer stands securely on the foundation established in Pennoyer. We think that the time is ripe to consider whether the standard of fairness and substantial justice set forth in International Shoe should be held to govern actions in rem as well as in personam.

III

The case for applying to jurisdiction in rem the same test of “fair play and substantial justice” as governs assertions of jurisdiction in personam is simple and straightforward. It is premised on recognition that “[t]he phrase, ‘judicial jurisdiction over a thing,’ is a customary elliptical way of referring to jurisdiction over the interests of persons in a thing.”23 Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws § 56, introductory note. This recognition leads to the conclusion that in order to justify an exercise of jurisdiction in rem, the basis for jurisdiction must be sufficient to justify exercising “jurisdiction over the interests of persons in a thing.” The standard for determining whether an exercise of jurisdiction over the interests of persons is consistent with the Due Process Clause is the minimum contacts standard elucidated in International Shoe.

This argument, of course, does not ignore the fact that the presence of property in a State may bear on the existence of jurisdiction by providing contacts among the forum State, the defendant, and the litigation. For example, when claims to the property itself are the source of the underlying controversy between the plaintiff and the defendant, it would be unusual for the State where the property is located not to have jurisdiction. In such cases, the defendant’s claim to property located in the State would normally indicate that he expected to benefit from the State’s protection of his interest. The State’s strong interests in assuring the marketability of property within its borders and in providing a procedure for peaceful resolution of disputes about the possession of that property would also support jurisdiction, as would the likelihood that important records and witnesses will be found in the State. The presence of property may also favor jurisdiction in cases, such as suits for injury suffered on the land of an absentee owner, where the defendant’s ownership of the property is conceded but the cause of action is otherwise related to rights and duties growing out of that ownership.

It appears, therefore, that jurisdiction over many types of actions which now are or might be brought in rem would not be affected by a holding that any assertion of state-court jurisdiction must satisfy the International Shoe standard. For the type of quasi in rem action typified by Harris v. Balk and the present case, however, accepting the proposed analysis would result in significant change. These are cases where the property which now serves as the basis for state-court jurisdiction is completely unrelated to the plaintiff’s cause of action. Thus, although the presence of the defendant’s property in a State might suggest the existence of other ties among the defendant, the State, and the litigation, the presence of the property alone would not support the State’s jurisdiction.

[…]

Since acceptance of the International Shoe test would most affect this class of cases, we examine the arguments against adopting that standard as they relate to this category of litigation. Before doing so, however, we note that this type of case also presents the clearest illustration of the argument in favor of assessing assertions of jurisdiction by a single standard. For in cases such as Harris and this one, the only role played by the property is to provide the basis for bringing the defendant into court. Indeed, the express purpose of the Delaware sequestration procedure is to compel the defendant to enter a personal appearance. In such cases, if a direct assertion of personal jurisdiction over the defendant would violate the Constitution, it would seem that an indirect assertion of the jurisdiction should be equally impermissible.

The primary rationale for treating the presence of property as a sufficient basis for jurisdiction to adjudicate claims over which the State would not have jurisdiction if International Shoe applied is that a wrongdoer “should not be able to avoid payment of his obligations by the expedient of removing his assets to a place where he is not subject to an in personam suit.” Restatement § 66, Comment a.

This justification, however, does not explain why jurisdiction should be recognized without regard to whether the property is present in the State because of an effort to avoid the owner’s obligations. Nor does it support jurisdiction to adjudicate the underlying claim.

[…]

It might also be suggested that allowing in rem jurisdiction avoids the uncertainty inherent in the International Shoe standard and assures a plaintiff of a forum.37 We believe, however, that the fairness standard of International Shoe can be easily applied in the vast majority of cases. Moreover, when the existence of jurisdiction in a particular forum under International Shoe is unclear, the cost of simplifying the litigation by avoiding the jurisdictional question may be the sacrifice of “fair play and substantial justice.” That cost is too high.

We are left, then, to consider the significance of the long history of jurisdiction based solely on the presence of property in a State. […] “[T]raditional notions of fair play and substantial justice” can be as readily offended by the perpetuation of ancient forms that are no longer justified as by the adoption of new procedures that are inconsistent with the basic values of our constitutional heritage. The fiction that an assertion of jurisdiction over property is anything but an assertion of jurisdiction over the owner of the property supports an ancient form without substantial modern justification. Its continued acceptance would serve only to allow state court jurisdiction that is fundamentally unfair to the defendant.

We therefore conclude that all assertions of state court jurisdiction must be evaluated according to the standards set forth in International Shoe and its progeny.39

IV

The Delaware courts based their assertion of jurisdiction in this case solely on the statutory presence of appellants’ property in Delaware. Yet that property is not the subject matter of this litigation, nor is the underlying cause of action related to the property. Appellants’ holdings in Greyhound do not, therefore, provide contacts with Delaware sufficient to support the jurisdiction of that State’s courts over appellants. If it exists, that jurisdiction must have some other foundation.

Appellee Heitner did not allege and does not now claim that appellants have ever set foot in Delaware. Nor does he identify any act related to his cause of action as having taken place in Delaware. Nevertheless, he contends that appellants’ positions as directors and officers of a corporation chartered in Delaware provide sufficient “contacts, ties, or relations,” International Shoe Co. v. Washington, with that State to give its courts jurisdiction over appellants in this stockholder’s derivative action. This argument is based primarily on what Heitner asserts to be the strong interest of Delaware in supervising the management of a Delaware corporation. That interest is said to derive from the role of Delaware law in establishing the corporation and defining the obligations owed to it by its officers and directors. In order to protect this interest, appellee concludes, Delaware’s courts must have jurisdiction over corporate fiduciaries such as appellants.

[…]

[But] Appellants have simply had nothing to do with the State of Delaware. Moreover, appellants had no reason to expect to be haled before a Delaware court. Delaware, unlike some States, has not enacted a statute that treats acceptance of a directorship as consent to jurisdiction in the State. And “[i]t strains reason … to suggest that anyone buying securities in a corporation formed in Delaware ‘impliedly consents’ to subject himself to Delaware’s … jurisdiction on any cause of action.” Appellants, who were not required to acquire interests in Greyhound in order to hold their positions, did not by acquiring those interests surrender their right to be brought to judgment only in States with which they had “minimum contacts.” The Due Process Clause

“does not contemplate that a state may make binding a judgment … against an individual or corporate defendant with which the state has no contacts, ties, or relations.” International Shoe Co. v. Washington.

Delaware’s assertion of jurisdiction over appellants in this case is inconsistent with that constitutional limitation on state power. The judgment of the Delaware Supreme Court must, therefore, be reversed.

It is so ordered.

REHNQUIST, J., took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.

POWELL, J., concurring.

I agree that the principles of International Shoe Co. v. Washington should be extended to govern assertions of in rem as well as in personam jurisdiction in state court. I also agree that neither the statutory presence of appellants’ stock in Delaware nor their positions as directors and officers of a Delaware corporation can provide sufficient contacts to support the Delaware courts’ assertion of jurisdiction in this case.

I would explicitly reserve judgment, however, on whether the ownership of some forms of property whose situs is indisputably and permanently located within a State may, without more, provide the contacts necessary to subject a defendant to jurisdiction within the State to the extent of the value of the property. In the case of real property, in particular, preservation of the common law concept of quasi in rem jurisdiction arguably would avoid the uncertainty of the general International Shoe standard without significant cost to “traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.” Subject to that reservation, I join the opinion of the Court.

STEVENS, J., concurring in the judgment.

The Due Process Clause affords protection against “judgments without notice.” International Shoe Co. v. Washington (opinion of Black, J.).

[…]

One who purchases shares of stock on the open market can hardly be expected to know that he has thereby become subject to suit in a forum remote from his residence and unrelated to the transaction. As a practical matter, the Delaware sequestration statute created an unacceptable risk of judgment without notice […] . I therefore agree with the Court that on the record before us no adequate basis for jurisdiction exists and that the Delaware statute is unconstitutional on its face.

How the Court’s opinion may be applied in other contexts is not entirely clear to me. […] My uncertainty as to the reach of the opinion, and my fear that it purports to decide a great deal more than is necessary to dispose of this case, persuade me merely to concur in the judgment.

BRENNAN, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part.