12 Subject-Matter Jurisdiction

12.1 Federal Question

Subject-matter jurisdiction refers to the power of a court to entertain certain types of disputes. Compare that with personal jurisdiction, which regulates when courts have power over certain parties. This difference gives rise to one of the most important distinctions between subject-matter and personal jurisdiction: the latter, as a personal right held by the defendant, can be waived. Subject-matter jurisdiction, by contrast, is a hard limit on court power, and so it cannot be consented to, waived, or ignored. Indeed, even when the parties do not raise the issue of subject-matter jurisdiction, courts have an independent obligation to investigate it for themselves.

Subject-matter jurisdiction does, however, share several key features with personal jurisdiction: both are threshold issues that must be addressed before the merits of a case, and defects in either type of jurisdiction can render an otherwise-final judgment unenforceable in a subsequent action. Similarly, like personal jurisdiction, subject-matter jurisdiction requires both a statutory and a constitutional grounding.

We will begin our study of subject-matter jurisdiction with one of the chief categories of cases federal courts are empowered to hear: those “arising under” federal law. The next case lays out the constitutional limits on this jurisdictional grant, which derive from Article III, § 2 of the Constitution. That provision states: “The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority.”

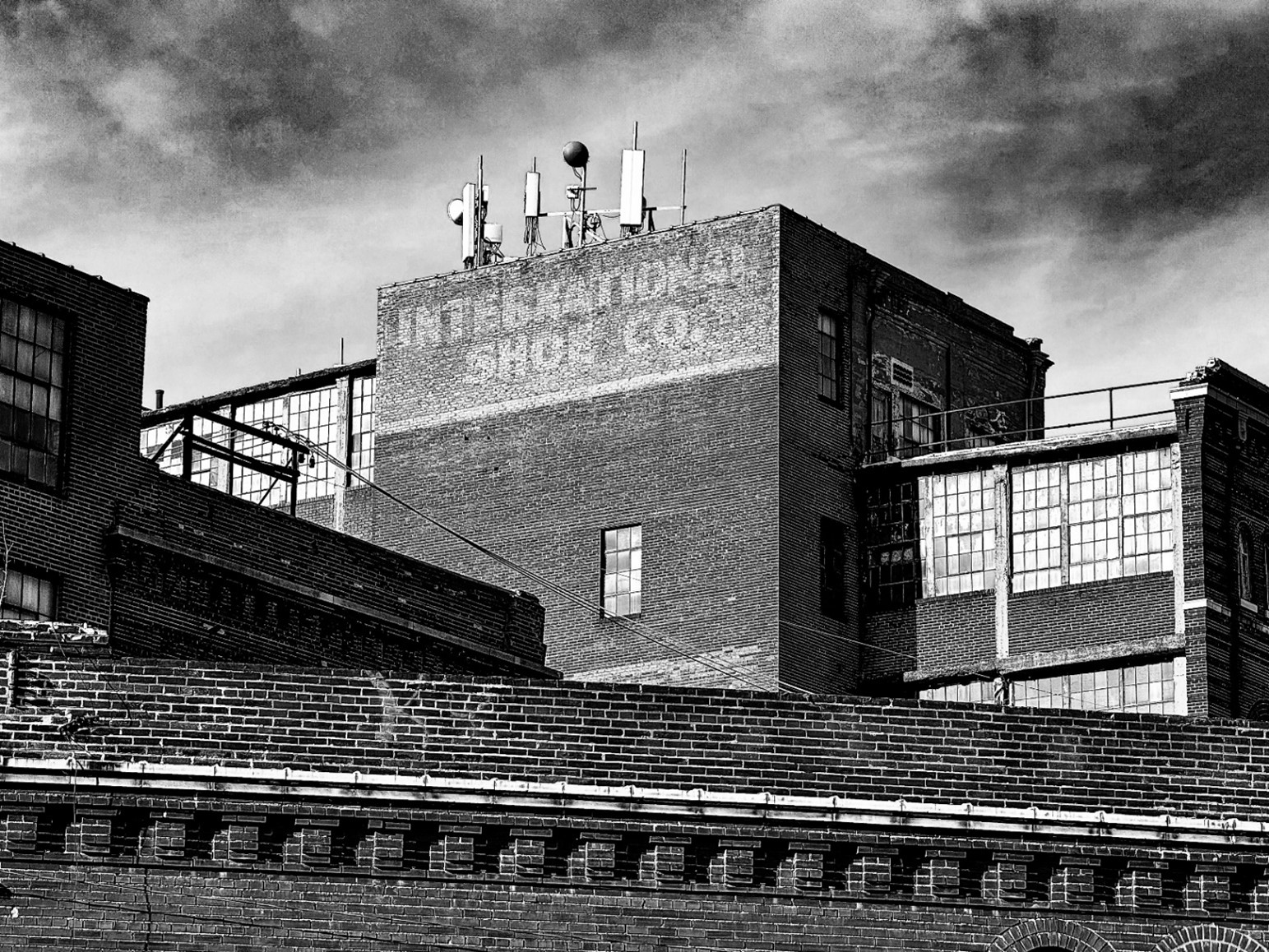

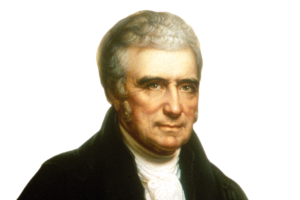

Osborn v. Bank of the United States

Mr. Chief Justice MARSHALL delivered the opinion of the Court:

[…]

[The Bank of the United States sued Ohio tax officials in federal court seeking to enjoin the state from collecting tax from the Bank. The lower court granted a temporary injunction. Ohio ignored the injunction and seized the tax allegedly owed by force. The federal court ordered the state officials to return the money. The state officials appealed on the grounds that the federal court lacked subject-matter jurisdiction. The statute creating the Bank authorized it “to sue and be sued … in any Circuit Court of the United States.” A key question on appeal was whether this statutory grant of subject-matter jurisdiction exceeded the jurisdictional limits of Article III, § 2 of the Constitution. In particular, the Court analyzed whether a suit in which the Bank is a party automatically “aris[es] under” federal law.]

When [the] Bank sues, the first question which presents itself, and which lies at the foundation of the cause, is, has this legal entity a right to sue? Has it a right to come, not into this Court particularly, but into any Court? This depends on a law of the United States. The next question is, has this being a right to make this particular contract? If this question be decided in the negative, the cause is determined against the plaintiff; and this question, too, depends entirely on a law of the United States. These are important questions, and they exist in every possible case. The right to sue, if decided once, is decided for ever; but the power of Congress was exercised antecedently to the first decision on that right, and if it was constitutional then, it cannot cease to be so, because the particular question is decided. It may be revived at the will of the party, and most probably would be renewed, were the tribunal to be changed. But the question respecting the right to make a particular contract, or to acquire a particular property, or to sue on account of a particular injury, belongs to every particular case, and may be renewed in every case. The question forms an original ingredient in every cause. Whether it be in fact relied on or not, in the defence, it is still a part of the cause, and may be relied on. The right of the plaintiff to sue, cannot depend on the defence which the defendant may choose to set up. His right to sue is anterior to that defence, and must depend on the state of things when the action is brought. The questions which the case involves, then, must determine its character, whether those questions be made in the cause or not.

The appellants say, that the case arises on the contract; but the validity of the contract depends on a law of the United States, and the plaintiff is compelled, in every case, to show its validity. The case arises emphatically under the law. The act of Congress is its foundation. The contract could never have been made, but under the authority of that act. The act itself is the first ingredient in the case, is its origin, is that from which every other part arises. That other questions may also arise, as the execution of the contract, or its performance, cannot change the case, or give it any other origin than the charter of incorporation. The action still originates in, and is sustained by, that charter.

[…]

Notes & Questions

- Osborn held that the Article III test for federal question jurisdiction is satisfied whenever federal law forms an “original ingredient” in the cause of action. This test does not require that the federal issue be litigated or even disputed. This is a very broad test.

- Before the Civil War, Congress did not often exercise its power to give federal courts subject-matter jurisdiction over federal questions. But in the late 19th century, such statutory grants proliferated. Today, the key statute is 28 U.S.C. § 1331, which provides that “district courts shall have original jurisdiction of all civil actions arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.” Note that the language of § 1331 is quite similar to the relevant language of Article III, § 2. Yet as the following cases show, courts have interpreted the statutory grant under § 1331 much more narrowly than the broad interpretation the Osborn Court gave to Article III.

Louisville & Nashville Railroad v. Mottley

MOODY, J., delivered the opinion of the Court.

[Erasmus and Annie Mottley were injured in a railroad accident. They sued the railroad, which agreed to settle the suit by giving the Mottleys free lifetime travel passes. Decades later, out of concern that free passes for railroad travel were a vector for political bribery and corruption, Congress banned them. That prompted the railroad to tell the Mottleys that they could not use the passes any longer. The Mottleys sued for breach of contract in federal court and requested specific performance as a remedy. The lower court denied the motion to dismiss, and the railroad appealed.]

Two questions of law were raised by the demurrer to the bill, were brought here by appeal, and have been argued before us. They are, first, whether that part of the act of Congress of June 29, 1906 (34 Stat. 584), which forbids the giving of free passes or the collection of any different compensation for transportation of passengers than that specified in the tariff filed, makes it unlawful to perform a contract for transportation of persons, who in good faith, before the passage of the act, had accepted such contract in satisfaction of a valid cause of action against the railroad; and, second, whether the statute, if it should be construed to render such a contract unlawful, is in violation of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. We do not deem it necessary, however, to consider either of these questions, because, in our opinion, the court below was without jurisdiction of the cause. Neither party has questioned that jurisdiction, but it is the duty of this court to see to it that the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court, which is defined and limited by statute, is not exceeded. This duty we have frequently performed of our own motion.

There was no diversity of citizenship and it is not and cannot be suggested that there was any ground of jurisdiction, except that the case was a “suit … arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States.” [The Court cited the then-current version of the “arising under” jurisdiction statute.] It is the settled interpretation of these words, as used in this statute, conferring jurisdiction, that a suit arises under the Constitution and laws of the United States only when the plaintiff’s statement of his own cause of action shows that it is based upon those laws or that Constitution. It is not enough that the plaintiff alleges some anticipated defense to his cause of action and asserts that the defense is invalidated by some provision of the Constitution of the United States. Although such allegations show that very likely, in the course of the litigation, a question under the Constitution would arise, they do not show that the suit, that is, the plaintiff’s original cause of action, arises under the Constitution. In Tennessee v. Union & Planters’ Bank, 152 U.S. 454, the plaintiff, the State of Tennessee, brought suit in the Circuit Court of the United States to recover from the defendant certain taxes alleged to be due under the laws of the State. The plaintiff alleged that the defendant claimed an immunity from the taxation by virtue of its charter, and that therefore the tax was void, because in violation of the provision of the Constitution of the United States, which forbids any State from passing a law impairing the obligation of contracts. The cause was held to be beyond the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court, the court saying, by Mr. Justice Gray, “a suggestion of one party, that the other will or may set up a claim under the Constitution or laws of the United States, does not make the suit one arising under that Constitution or those laws.” Again, in Boston & Montana Consolidated Copper & Silver Mining Company v. Montana Ore Purchasing Company, 188 U.S. 632, the […] cause was held to be beyond the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court, the court saying, by Mr. Justice Peckham:

It would be wholly unnecessary and improper in order to prove complainant’s cause of action to go into any matters of defence which the defendants might possibly set up and then attempt to reply to such defence, and thus, if possible, to show that a Federal question might or probably would arise in the course of the trial of the case. To allege such defence and then make an answer to it before the defendant has the opportunity to itself plead or prove its own defence is inconsistent with any known rule of pleading so far as we are aware, and is improper.

The rule is a reasonable and just one that the complainant in the first instance shall be confined to a statement of its cause of action, leaving to the defendant to set up in his answer what his defence is and, if anything more than a denial of complainant’s cause of action, imposing upon the defendant the burden of proving such defence.

Conforming itself to that rule the complainant would not, in the assertion or proof of its cause of action, bring up a single Federal question. The presentation of its cause of action would not show that it was one arising under the Constitution or laws of the United States.

The only way in which it might be claimed that a Federal question was presented would be in the complainant’s statement of what the defence of defendants would be and complainant’s answer to such defence. Under these circumstances the case is brought within the rule laid down in Tennessee v. Union & Planters’ Bank, 152 U.S. 454 [holding that such cases do not arise under federal law].

[…] The application of this rule to the case at bar is decisive against the jurisdiction of the circuit court.

It is ordered that the judgment be reversed and the case remitted to the circuit court with instructions to dismiss for want of jurisdiction.

Notes & Questions

- Mottley held that, in determining whether a suit arises under federal law for purposes of § 1331, courts must look only at the plaintiff’s complaint, and not any defenses that the defendant might raise in response. This rule, known as the “well-pleaded complaint rule,” applies only under § 1331 and not under Article III.

- A corollary, known as the “artful pleading” rule, says that plaintiffs may not plead the denial of an anticipated federal defense and thereby render their claim one that arises under federal law. Instead, courts must look to the elements of the plaintiff’s cause of action to determine whether it raises a federal question.

- Does it make sense to ignore likely federal defenses in determining whether a case “arises under” federal law? What theory might support allowing federal questions embedded in a complaint to be filed in federal court, but relegating significant federal questions raised only in defense to state court?

- Does it make sense to read the language of § 1331 so differently from that of Art. III, given that they are so textually similar? Even if not, do you think Congress implicitly blessed the divergence between statute and constitution by refusing to expand federal-question jurisdiction to encompass federal defenses, despite many other amendments to § 1331 and its predecessors over the years?

- While Mottley rules out federal question jurisdiction based only on a federal defense, it leaves open the question of when a plaintiff’s complaint “arises under” federal law. Does it require that the plaintiff’s cause of action be a creation of federal law, or can the test be satisfied if the plaintiff pleads a state-law claim that necessarily involves federal law? The following cases seek to work out the answer to this question.

American Well Works Co. v. Layne & Bowler Co.

Mr. Justice Holmes delivered the opinion of the court.

This is a suit begun in a state court, removed to the United States Court, and then, on motion to remand by the plaintiff, dismissed by the latter court, on the ground that the cause of action arose under the patent laws of the United States, that the state court had no jurisdiction, and that therefore the one to which it was removed had none. […]

[…] The plaintiff alleges that it owns, manufactures and sells a certain pump, has or has applied for a patent for it, and that the pump is known as the best in the market. It then alleges that the defendants have falsely and maliciously libeled and slandered the plaintiff’s title to the pump by stating that the pump and certain parts thereof are infringements upon the defendant’s pump and certain parts thereof and that without probable cause they have brought suits against some parties who are using the plaintiff’s pump and that they are threatening suits against all who use it. The allegation of the defendants’ libel or slander is repeated in slightly varying form but it all comes to statements to various people that the plaintiff was infringing the defendants’ patent and that the defendant would sue both seller and buyer if the plaintiff’s pump was used. Actual damage to the plaintiff in its business is alleged to the extent of $50,000 and punitive damages to the same amount are asked.

[…]

A suit for damages to business caused by a threat to sue under the patent law is not itself a suit under the patent law. And the same is true when the damage is caused by a statement of fact—that the defendant has a patent which is infringed. What makes the defendants’ act a wrong is its manifest tendency to injure the plaintiff’s business and the wrong is the same whatever the means by which it is accomplished. But whether it is a wrong or not depends upon the law of the State where the act is done, not upon the patent law, and therefore the suit arises under the law of the State. A suit arises under the law that creates the cause of action. The fact that the justification may involve the validity and infringement of a patent is no more material to the question under what law the suit is brought than it would be in an action of contract. […] The State is master of the whole matter, and if it saw fit to do away with actions of this type altogether, no one, we imagine, would suppose that they still could be maintained under the patent laws of the United States.

Judgment reversed.

Notes & Questions

- The rule of American Well-Works is that “[a] suit arises under the law that creates the cause of action.” In other words, if a cause of action is created by federal law, it “arises under” federal law; if it is created by state law, it does not. This rule has an obvious strength: it is quite clear and easily applied. But does that advantage come at the cost of relegating some significant questions of federal law to the domain of state courts, at least in the first instance?

- Justice Holmes’s vision for a clear, bright-line rule faded quickly. As the legendary Second Circuit Judge Henry Friendly put it, “Mr. Justice Holmes’ formula is more useful for inclusion than for the exclusion for which it was intended. Even though the claim is created by state law, a case may ‘arise under’ a law of the United States if the complaint discloses a need for determining the meaning or application of such a law.” TB Harms Co. v. Eliscu, 339 F.2d 823, 827 (2d Cir. 1964). The case that follows shows why.

Smith v. Kansas City Title & Trust Co.

MR. JUSTICE DAY delivered the opinion of the court.

A bill was filed in the United States District Court for the Western Division of the Western District of Missouri by a shareholder in the Kansas City Title & Trust Company to enjoin the Company, its officers, agents and employees from investing the funds of the Company in farm loan bonds issued by Federal Land Banks or Joint Stock Land Banks under authority of the Federal Farm Loan Act of July 17, 1916.

The relief was sought on the ground that these acts were beyond the constitutional power of Congress. The bill avers that the Board of Directors of the Company are about to invest its funds in the bonds to the amount of $10,000 in each of the classes described, and will do so unless enjoined by the court in this action. […]

As diversity of citizenship is lacking, the jurisdiction of the District Court depends upon whether the cause of action set forth arises under the Constitution or laws of the United States.

The general rule is that where it appears from the bill or statement of the plaintiff that the right to relief depends upon the construction or application of the Constitution or laws of the United States, and that such federal claim is not merely colorable, and rests upon a reasonable foundation, the District Court has jurisdiction under this provision.

[…]

In the instant case the averments of the bill show that the directors were proceeding to make the investments in view of the act authorizing the bonds about to be purchased, maintaining that the act authorizing them was constitutional and the bonds valid and desirable investments. The objecting shareholder avers in the bill that the securities were issued under an unconstitutional law, and hence of no validity. It is, therefore, apparent that the controversy concerns the constitutional validity of an act of Congress which is directly drawn in question. The decision depends upon the determination of this issue.

[…] We are, therefore, of the opinion that the District Court had jurisdiction […].

MR. JUSTICE HOLMES, dissenting.

No doubt it is desirable that the question raised in this case should be set at rest, but that can be done by the Courts of the United States only within the limits of the jurisdiction conferred upon them by the Constitution and the laws of the United States. As this suit was brought by a citizen of Missouri against a Missouri corporation the single ground upon which the jurisdiction of the District Court can be maintained is that the suit “arises under the Constitution or laws of the United States” within the meaning of § 24 of the Judicial Code. I am of opinion that this case does not arise in that way and therefore that the bill should have been dismissed.

[I]t seems to me that a suit cannot be said to arise under any other law than that which creates the cause of action. It may be enough that the law relied upon creates a part of the cause of action although not the whole, as held in Osborn v. Bank of the United States […], although the Osborn Case has been criticized and regretted. But the law must create at least a part of the cause of action by its own force, for it is the suit, not a question in the suit, that must arise under the law of the United States. The mere adoption by a state law of a United States law as a criterion or test, when the law of the United States has no force proprio vigore, does not cause a case under the state law to be also a case under the law of the United States […].

[…]

Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Thompson

JUSTICE STEVENS delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question presented is whether the incorporation of a federal standard in a state-law private action, when Congress has intended that there not be a federal private action for violations of that federal standard, makes the action one “arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States,” 28 U.S.C. § 1331.

I

The Thompson respondents are residents of Canada and the MacTavishes reside in Scotland. They filed virtually identical complaints against petitioner, a corporation, that manufactures and distributes the drug Bendectin. The complaints were filed in the Court of Common Pleas in Hamilton County, Ohio. Each complaint alleged that a child was born with multiple deformities as a result of the mother’s ingestion of Bendectin during pregnancy. In five of the six counts, the recovery of substantial damages was requested on common-law theories of negligence, breach of warranty, strict liability, fraud, and gross negligence. In Count IV, respondents alleged that the drug Bendectin was “misbranded” in violation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), because its labeling did not provide adequate warning that its use was potentially dangerous. Paragraph 26 alleged that the violation of the FDCA “in the promotion” of Bendectin “constitutes a rebuttable presumption of negligence.” Paragraph 27 alleged that the “violation of said federal statutes directly and proximately caused the injuries suffered” by the two infants.

Petitioner filed a timely petition for removal from the state court to the Federal District Court alleging that the action was “founded, in part, on an alleged claim arising under the laws of the United States.” After removal, the two cases were consolidated. Respondents filed a motion to remand to the state forum on the ground that the federal court lacked subject-matter jurisdiction. Relying on our decision in Smith v. Kansas City Title & Trust Co., the District Court held that Count IV of the complaint alleged a cause of action arising under federal law and denied the motion to remand. It then granted petitioner’s motion to dismiss on forum non conveniens grounds.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed. After […] noting “that the FDCA does not create or imply a private right of action for individuals injured as a result of violations of the Act,” it explained:

Federal question jurisdiction would, thus, exist only if plaintiffs’ right to relief depended necessarily on a substantial question of federal law. Plaintiffs’ causes of action referred to the FDCA merely as one available criterion for determining whether Merrell Dow was negligent. Because the jury could find negligence on the part of Merrell Dow without finding a violation of the FDCA, the plaintiffs’ causes of action did not depend necessarily upon a question of federal law. Consequently, the causes of action did not arise under federal law and, therefore, were improperly removed to federal court.

We granted certiorari, and we now affirm.

II

Article III of the Constitution gives the federal courts power to hear cases “arising under” federal statutes. That grant of power, however, is not self-executing, and it was not until the Judiciary Act of 1875 that Congress gave the federal courts general federal-question jurisdiction. Although the constitutional meaning of “arising under” may extend to all cases in which a federal question is “an ingredient” of the action, Osborn v. Bank of the United States, we have long construed the statutory grant of federal-question jurisdiction as conferring a more limited power.

Under our longstanding interpretation of the current statutory scheme, the question whether a claim “arises under” federal law must be determined by reference to the “well-pleaded complaint.” A defense that raises a federal question is inadequate to confer federal jurisdiction. Louisville & Nashville R. Co. v. Mottley. Since a defendant may remove a case only if the claim could have been brought in federal court, 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b), moreover, the question for removal jurisdiction must also be determined by reference to the “well-pleaded complaint.”

[…]

The “vast majority” of cases that come within this grant of jurisdiction are covered by Justice Holmes’ statement that a “suit arises under the law that creates the cause of action.” American Well Works Co. v. Layne & Bowler Co. Thus, the vast majority of cases brought under the general federal-question jurisdiction of the federal courts are those in which federal law creates the cause of action.

We have, however, also noted that a case may arise under federal law “where the vindication of a right under state law necessarily turned on some construction of federal law.” […]

This case does not pose a federal question of the first kind; respondents do not allege that federal law creates any of the causes of action that they have asserted. This case thus poses what Justice Frankfurter called the “litigation-provoking problem,” the presence of a federal issue in a state-created cause of action.

[…] We have consistently emphasized that, in exploring the outer reaches of § 1331, determinations about federal jurisdiction require sensitive judgments about congressional intent, judicial power, and the federal system. […]

In this case, both parties agree with the Court of Appeals’ conclusion that there is no federal cause of action for FDCA violations. For purposes of our decision, we assume that this is a correct interpretation of the FDCA. […] In short, Congress did not intend a private federal remedy for violations of the statute that it enacted.

[…]

The significance of the necessary assumption that there is no federal private cause of action thus cannot be overstated. For the ultimate import of such a conclusion, as we have repeatedly emphasized, is that it would flout congressional intent to provide a private federal remedy for the violation of the federal statute. We think it would similarly flout, or at least undermine, congressional intent to conclude that the federal courts might nevertheless exercise federal-question jurisdiction and provide remedies for violations of that federal statute solely because the violation of the federal statute is said to be a “rebuttable presumption” or a “proximate cause” under state law, rather than a federal action under federal law.

III

Petitioner […] argues that, whatever the general rule, there are special circumstances that justify federal-question jurisdiction in this case. Petitioner emphasizes that it is unclear whether the FDCA applies to sales in Canada and Scotland; there is, therefore, a special reason for having a federal court answer the novel federal question relating to the extra-territorial meaning of the Act. We reject this argument. We do not believe the question whether a particular claim arises under federal law depends on the novelty of the federal issue. Although it is true that federal jurisdiction cannot be based on a frivolous or insubstantial federal question, “the interrelation of federal and state authority and the proper management of the federal judicial system” would be ill served by a rule that made the existence of federal-question jurisdiction depend on the district court’s case-by-case appraisal of the novelty of the federal question asserted as an element of the state tort. The novelty of an FDCA issue is not sufficient to give it status as a federal cause of action; nor should it be sufficient to give a state-based FDCA claim status as a jurisdiction-triggering federal question.

IV

We conclude that a complaint alleging a violation of a federal statute as an element of a state cause of action, when Congress has determined that there should be no private, federal cause of action for the violation, does not state a claim “arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1331.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is affirmed.

It is so ordered.

Grable & Sons Metal Prods., Inc. v. Darue Eng’g & Mfg.

JUSTICE SOUTER delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question is whether want of a federal cause of action to try claims of title to land obtained at a federal tax sale precludes removal to federal court of a state action with nondiverse parties raising a disputed issue of federal title law. We answer no, and hold that the national interest in providing a federal forum for federal tax litigation is sufficiently substantial to support the exercise of federal-question jurisdiction over the disputed issue on removal, which would not distort any division of labor between the state and federal courts, provided or assumed by Congress.

I

In 1994, the Internal Revenue Service seized Michigan real property belonging to petitioner Grable & Sons Metal Products, Inc., to satisfy Grable’s federal tax delinquency. Title 26 U.S.C. § 6335 required the IRS to give notice of the seizure, and there is no dispute that Grable received actual notice by certified mail before the IRS sold the property to respondent Darue Engineering & Manufacturing. Although Grable also received notice of the sale itself, it did not exercise its statutory right to redeem the property within 180 days of the sale, and after that period had passed, the Government gave Darue a quitclaim deed.

Five years later, Grable brought a quiet title action in state court, claiming that Darue’s record title was invalid because the IRS had failed to notify Grable of its seizure of the property in the exact manner required by § 6335(a), which provides that written notice must be “given by the Secretary to the owner of the property [or] left at his usual place of abode or business.” Grable said that the statute required personal service, not service by certified mail.

Darue removed the case to Federal District Court as presenting a federal question, because the claim of title depended on the interpretation of the notice statute in the federal tax law. The District Court declined to remand the case at Grable’s behest after finding that the “claim does pose a significant question of federal law” and ruling that Grable’s lack of a federal right of action to enforce its claim against Darue did not bar the exercise of federal jurisdiction. […]

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed. On the jurisdictional question, the panel thought it sufficed that the title claim raised an issue of federal law that had to be resolved, and implicated a substantial federal interest (in construing federal tax law). […] We granted certiorari […] to resolve a split within the Courts of Appeals on whether Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Thompson, always requires a federal cause of action as a condition for exercising federal-question jurisdiction. We now affirm.

II

Darue was entitled to remove the quiet title action if Grable could have brought it in federal district court originally, 28 U.S.C. § 1441(a), as a civil action “arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States,” § 1331. This provision for federal-question jurisdiction is invoked by and large by plaintiffs pleading a cause of action created by federal law (e.g., claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983). There is, however, another longstanding, if less frequently encountered, variety of federal “arising under” jurisdiction, this Court having recognized for nearly 100 years that in certain cases federal-question jurisdiction will lie over state-law claims that implicate significant federal issues. The doctrine captures the commonsense notion that a federal court ought to be able to hear claims recognized under state law that nonetheless turn on substantial questions of federal law, and thus justify resort to the experience, solicitude, and hope of uniformity that a federal forum offers on federal issues.

The classic example is Smith v. Kansas City Title & Trust Co., a suit by a shareholder claiming that the defendant corporation could not lawfully buy certain bonds of the National Government because their issuance was unconstitutional. Although Missouri law provided the cause of action, the Court recognized federal-question jurisdiction because the principal issue in the case was the federal constitutionality of the bond issue. Smith thus held, in a somewhat generous statement of the scope of the doctrine, that a state-law claim could give rise to federal-question jurisdiction so long as it “appears from the [complaint] that the right to relief depends upon the construction or application of [federal law].”

The Smith statement has been subject to some trimming to fit earlier and later cases recognizing the vitality of the basic doctrine, but shying away from the expansive view that mere need to apply federal law in a state-law claim will suffice to open the “arising under” door. As early as 1912, this Court had confined federal-question jurisdiction over state-law claims to those that “really and substantially involv[e] a dispute or controversy respecting the validity, construction or effect of [federal] law.” This limitation was the ancestor of Justice Cardozo’s later explanation that a request to exercise federal-question jurisdiction over a state action calls for a “common-sense accommodation of judgment to [the] kaleidoscopic situations” that present a federal issue, in “a selective process which picks the substantial causes out of the web and lays the other ones aside.” It has in fact become a constant refrain in such cases that federal jurisdiction demands not only a contested federal issue, but a substantial one, indicating a serious federal interest in claiming the advantages thought to be inherent in a federal forum.

But even when the state action discloses a contested and substantial federal question, the exercise of federal jurisdiction is subject to a possible veto. For the federal issue will ultimately qualify for a federal forum only if federal jurisdiction is consistent with congressional judgment about the sound division of labor between state and federal courts governing the application of § 1331. […] Because arising-under jurisdiction to hear a state-law claim always raises the possibility of upsetting the state-federal line drawn (or at least assumed) by Congress, the presence of a disputed federal issue and the ostensible importance of a federal forum are never necessarily dispositive; there must always be an assessment of any disruptive portent in exercising federal jurisdiction. See also Merrell Dow.

These considerations have kept us from stating a “single, precise, all-embracing” test for jurisdiction over federal issues embedded in state-law claims between nondiverse parties. We have not kept them out simply because they appeared in state raiment, as Justice Holmes would have done, see Smith (dissenting opinion), but neither have we treated “federal issue” as a password opening federal courts to any state action embracing a point of federal law. Instead, the question is, does a state-law claim necessarily raise a stated federal issue, actually disputed and substantial, which a federal forum may entertain without disturbing any congressionally approved balance of federal and state judicial responsibilities.

III

A

This case warrants federal jurisdiction. Grable’s state complaint must specify “the facts establishing the superiority of [its] claim,” Mich. Ct. Rule 3.411(B)(2)(c), and Grable has premised its superior title claim on a failure by the IRS to give it adequate notice, as defined by federal law. Whether Grable was given notice within the meaning of the federal statute is thus an essential element of its quiet title claim, and the meaning of the federal statute is actually in dispute; it appears to be the only legal or factual issue contested in the case. The meaning of the federal tax provision is an important issue of federal law that sensibly belongs in a federal court. The Government has a strong interest in the “prompt and certain collection of delinquent taxes,” and the ability of the IRS to satisfy its claims from the property of delinquents requires clear terms of notice to allow buyers like Darue to satisfy themselves that the Service has touched the bases necessary for good title. The Government thus has a direct interest in the availability of a federal forum to vindicate its own administrative action, and buyers (as well as tax delinquents) may find it valuable to come before judges used to federal tax matters. Finally, because it will be the rare state title case that raises a contested matter of federal law, federal jurisdiction to resolve genuine disagreement over federal tax title provisions will portend only a microscopic effect on the federal-state division of labor.

[…]

B

Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Thompson, on which Grable rests its position, is not to the contrary. Merrell Dow considered a state tort claim resting in part on the allegation that the defendant drug company had violated a federal misbranding prohibition, and was thus presumptively negligent under Ohio law. The Court assumed that federal law would have to be applied to resolve the claim, but after closely examining the strength of the federal interest at stake and the implications of opening the federal forum, held federal jurisdiction unavailable. Congress had not provided a private federal cause of action for violation of the federal branding requirement, and the Court found “it would … flout, or at least undermine, congressional intent to conclude that federal courts might nevertheless exercise federal-question jurisdiction and provide remedies for violations of that federal statute solely because the violation … is said to be a … ‘proximate cause’ under state law.”

Because federal law provides for no quiet title action that could be brought against Darue, Grable argues that there can be no federal jurisdiction here, stressing some broad language in Merrell Dow (including the passage just quoted) that on its face supports Grable’s position. But an opinion is to be read as a whole, and Merrell Dow cannot be read whole as overturning decades of precedent, as it would have done by effectively adopting the Holmes dissent in Smith and converting a federal cause of action from a sufficient condition for federal-question jurisdiction into a necessary one.

In the first place, Merrell Dow disclaimed the adoption of any bright-line rule, as when the Court reiterated that “in exploring the outer reaches of § 1331, determinations about federal jurisdiction require sensitive judgments about congressional intent, judicial power, and the federal system.” […] And as a final indication that it did not mean to make a federal right of action mandatory, it expressly approved the exercise of jurisdiction sustained in Smith, despite the want of any federal cause of action available to Smith’s shareholder plaintiff. Merrell Dow then, did not toss out, but specifically retained, the contextual enquiry that had been Smith’s hallmark for over 60 years. At the end of Merrell Dow, Justice Holmes was still dissenting.

Accordingly, Merrell Dow should be read in its entirety as treating the absence of a federal private right of action as evidence relevant to, but not dispositive of, the “sensitive judgments about congressional intent” that § 1331 requires. The absence of any federal cause of action affected Merrell Dow’s result two ways. The Court saw the fact as worth some consideration in the assessment of substantiality. But its primary importance emerged when the Court treated the combination of no federal cause of action and no preemption of state remedies for misbranding as an important clue to Congress’s conception of the scope of jurisdiction to be exercised under § 1331. The Court saw the missing cause of action not as a missing federal door key, always required, but as a missing welcome mat, required in the circumstances, when exercising federal jurisdiction over a state misbranding action would have attracted a horde of original filings and removal cases raising other state claims with embedded federal issues. For if the federal labeling standard without a federal cause of action could get a state claim into federal court, so could any other federal standard without a federal cause of action. And that would have meant a tremendous number of cases.

One only needed to consider the treatment of federal violations generally in garden variety state tort law. “The violation of federal statutes and regulations is commonly given negligence per se effect in state tort proceedings.” Restatement (Third) of Torts § 14, Reporters’ Note, Comment a, p. 195 (Tent. Draft No. 1, Mar. 28, 2001). A general rule of exercising federal jurisdiction over state claims resting on federal mislabeling and other statutory violations would thus have heralded a potentially enormous shift of traditionally state cases into federal courts. Expressing concern over the “increased volume of federal litigation,” and noting the importance of adhering to “legislative intent,” Merrell Dow thought it improbable that the Congress, having made no provision for a federal cause of action, would have meant to welcome any state-law tort case implicating federal law “solely because the violation of the federal statute is said to [create] a rebuttable presumption [of negligence] … under state law.” In this situation, no welcome mat meant keep out. Merrell Dow’s analysis thus fits within the framework of examining the importance of having a federal forum for the issue, and the consistency of such a forum with Congress’s intended division of labor between state and federal courts.

As already indicated, however, a comparable analysis yields a different jurisdictional conclusion in this case. Although Congress also indicated ambivalence in this case by providing no private right of action to Grable, it is the rare state quiet title action that involves contested issues of federal law_._ Consequently, jurisdiction over actions like Grable’s would not materially affect, or threaten to affect, the normal currents of litigation. Given the absence of threatening structural consequences and the clear interest the Government, its buyers, and its delinquents have in the availability of a federal forum, there is no good reason to shirk from federal jurisdiction over the dispositive and contested federal issue at the heart of the state-law title claim.

IV

The judgment of the Court of Appeals, upholding federal jurisdiction over Grable’s quiet title action, is affirmed.

It is so ordered.

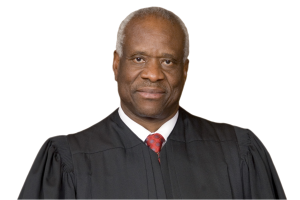

JUSTICE THOMAS, concurring.

[…] In this case, no one has asked us to overrule those precedents and adopt the rule Justice Holmes set forth in American Well Works Co. v. Layne & Bowler Co., limiting § 1331 jurisdiction to cases in which federal law creates the cause of action pleaded on the face of the plaintiff’s complaint. In an appropriate case, and perhaps with the benefit of better evidence as to the original meaning of § 1331’s text, I would be willing to consider that course.

Jurisdictional rules should be clear. Whatever the virtues of the Smith standard, it is anything but clear. Ante (the standard “calls for a ‘common-sense accommodation of judgment to [the] kaleidoscopic situations’ that present a federal issue, in ‘a selective process which picks the substantial causes out of the web and lays the other ones aside’”); ante (“[T]he question is, does a state-law claim necessarily raise a stated federal issue, actually disputed and substantial, which a federal forum may entertain without disturbing any congressionally approved balance of federal and state judicial responsibilities”); ante (“‘[D]eterminations about federal jurisdiction require sensitive judgments about congressional intent, judicial power, and the federal system’”; “the absence of a federal private right of action [is] evidence relevant to, but not dispositive of, the ‘sensitive judgments about congressional intent’ that § 1331 requires”).

Whatever the vices of the American Well Works rule, it is clear. Moreover, it accounts for the “vast majority” of cases that come within § 1331 under our current case law, further indication that trying to sort out which cases fall within the smaller Smith category may not be worth the effort it entails. Accordingly, I would be willing in appropriate circumstances to reconsider our interpretation of § 1331.

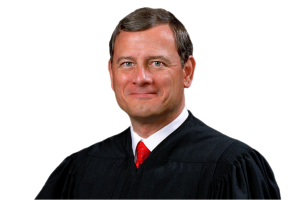

Gunn v. Minton

Chief Justice Roberts delivered the opinion of the Court.

Federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over cases “arising under any Act of Congress relating to patents.” 28 U.S.C. § 1338(a). The question presented is whether a state law claim alleging legal malpractice in the handling of a patent case must be brought in federal court.

I

[Vernon Minton created software to facilitate securities trading. He later patented his invention.]

Patent in hand, Minton filed a patent infringement suit in Federal District Court against the National Association of Securities Dealers, Inc. (NASD), and the NASDAQ Stock Market, Inc. He was represented by Jerry Gunn and the other petitioners. NASD and NASDAQ moved for summary judgment on the ground that Minton’s patent was invalid […].[T]he District Court granted the summary judgment motion and declared Minton’s patent invalid.

Minton then filed a motion for reconsideration in the District Court, arguing for the first time that […] the “experimental use” exception [under federal patent law applied and saved his patent from invalidity]. The District Court denied the motion.

Minton appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. That court affirmed, concluding that the District Court had appropriately held Minton’s experimental-use argument waived.

Minton, convinced that his attorneys’ failure to raise the experimental-use argument earlier had cost him the lawsuit and led to invalidation of his patent, brought this malpractice action in Texas state court. His former lawyers defended on the ground that […][the] experimental[-]use [exception did not apply] and that therefore Minton’s patent infringement claims would have failed even if the experimental-use argument had been timely raised. The trial court agreed, […][and] accordingly granted summary judgment to Gunn and the other lawyer defendants.

On appeal, Minton raised a new argument: Because his legal malpractice claim was based on an alleged error in a patent case, it “aris[es] under” federal patent law for purposes of 28 U.S.C. § 1338(a). And because, under § 1338(a), “[n]o State court shall have jurisdiction over any claim for relief arising under any Act of Congress relating to patents,” the Texas court—where Minton had originally brought his malpractice claim—lacked subject matter jurisdiction to decide the case. Accordingly, Minton argued, the trial court’s order should be vacated and the case dismissed, leaving Minton free to start over in the Federal District Court.

A divided panel of the Court of Appeals of Texas rejected Minton’s argument. Applying the test we articulated in Grable & Sons Metal Products, Inc. v. Darue Engineering & Mfg., it held that the federal interests implicated by Minton’s state law claim were not sufficiently substantial to trigger § 1338 “arising under” jurisdiction. It also held that finding exclusive federal jurisdiction over state legal malpractice actions would, contrary to Grable’s commands, disturb the balance of federal and state judicial responsibilities. […]

The Supreme Court of Texas reversed […]. The court concluded that Minton’s claim involved “a substantial federal issue” within the meaning of Grable “because the success of Minton’s malpractice claim is reliant upon the viability of the experimental use exception […].”

[…]

II

[…]

Adhering to the demands of “[l]inguistic consistency,” we have interpreted the phrase “arising under” in both [28 U.S.C. § 1331 and § 1338(a)] identically, applying our § 1331 and § 1338(a) precedents interchangeably. For cases falling within the patent specific arising under jurisdiction of § 1338(a), however, Congress has not only provided for federal jurisdiction but also eliminated state jurisdiction, decreeing that “[n]o State court shall have jurisdiction over any claim for relief arising under any Act of Congress relating to patents.” § 1338(a). To determine whether jurisdiction was proper in the Texas courts, therefore, we must determine whether it would have been proper in a federal district court—whether, that is, the case “aris[es] under any Act of Congress relating to patents.”

For statutory purposes, a case can “aris[e] under” federal law in two ways. Most directly, a case arises under federal law when federal law creates the cause of action asserted. See American Well Works Co. v. Layne & Bowler Co. (“A suit arises under the law that creates the cause of action”). As a rule of inclusion, this “creation” test admits of only extremely rare exceptions and accounts for the vast bulk of suits that arise under federal law. […]

But even where a claim finds its origins in state rather than federal law—as Minton’s legal malpractice claim indisputably does—we have identified a “special and small category” of cases in which arising under jurisdiction still lies. In outlining the contours of this slim category, we do not paint on a blank canvas. Unfortunately, the canvas looks like one that Jackson Pollock got to first.

In an effort to bring some order to this unruly doctrine several Terms ago, we condensed our prior cases into the following inquiry: Does the “state-law claim necessarily raise a stated federal issue, actually disputed and substantial, which a federal forum may entertain without disturbing any congressionally approved balance of federal and state judicial responsibilities?” Grable. That is, federal jurisdiction over a state law claim will lie if a federal issue is: (1) necessarily raised, (2) actually disputed, (3) substantial, and (4) capable of resolution in federal court without disrupting the federal-state balance approved by Congress. Where all four of these requirements are met, we held, jurisdiction is proper because there is a “serious federal interest in claiming the advantages thought to be inherent in a federal forum,” which can be vindicated without disrupting Congress’s intended division of labor between state and federal courts.

III

Applying Grable’s inquiry here, it is clear that Minton’s legal malpractice claim does not arise under federal patent law. Indeed, for the reasons we discuss, we are comfortable concluding that state legal malpractice claims based on underlying patent matters will rarely, if ever, arise under federal patent law for purposes of § 1338(a). Although such cases may necessarily raise disputed questions of patent law, those cases are by their nature unlikely to have the sort of significance for the federal system necessary to establish jurisdiction.

A

To begin, we acknowledge that resolution of a federal patent question is “necessary” to Minton’s case. Under Texas law, a plaintiff alleging legal malpractice must establish four elements: (1) that the defendant attorney owed the plaintiff a duty; (2) that the attorney breached that duty; (3) that the breach was the proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injury; and (4) that damages occurred. In cases like this one, in which the attorney’s alleged error came in failing to make a particular argument, the causation element requires a “case within a case” analysis of whether, had the argument been made, the outcome of the earlier litigation would have been different. To prevail on his legal malpractice claim, therefore, Minton must show that he would have prevailed in his federal patent infringement case if only petitioners had timely made an experimental-use argument on his behalf. […]

B

The federal issue is also “actually disputed” here—indeed, on the merits, it is the central point of dispute. Minton argues that the experimental-use exception properly applied […], saving his patent from [invalidity]; petitioners argue that it did not. This is just the sort of “‘dispute … respecting the … effect of [federal] law’” that Grable envisioned.

C

Minton’s argument founders on Grable’s next requirement, however, for the federal issue in this case is not substantial in the relevant sense. In reaching the opposite conclusion, the Supreme Court of Texas focused on the importance of the issue to the plaintiff’s case and to the parties before it. As our past cases show, however, it is not enough that the federal issue be significant to the particular parties in the immediate suit; that will always be true when the state claim “necessarily raise[s]” a disputed federal issue, as Grable separately requires. The substantiality inquiry under Grable looks instead to the importance of the issue to the federal system as a whole.

[…]

Here, the federal issue carries no such significance. Because of the backward-looking nature of a legal malpractice claim, the question is posed in a merely hypothetical sense: If Minton’s lawyers had raised a timely experimental-use argument, would the result in the patent infringement proceeding have been different? No matter how the state courts resolve that hypothetical “case within a case,” it will not change the real-world result of the prior federal patent litigation. Minton’s patent will remain invalid.

Nor will allowing state courts to resolve these cases undermine “the development of a uniform body of [patent] law.” Congress ensured such uniformity by vesting exclusive jurisdiction over actual patent cases in the federal district courts and exclusive appellate jurisdiction in the Federal Circuit. See 28 U.S.C. §§ 1338(a), 1295(a)(1). In resolving the nonhypothetical patent questions those cases present, the federal courts are of course not bound by state court case-within-a-case patent rulings. In any event, the state court case-within-a-case inquiry asks what would have happened in the prior federal proceeding if a particular argument had been made. In answering that question, state courts can be expected to hew closely to the pertinent federal precedents. […]

As for more novel questions of patent law that may arise for the first time in a state court “case within a case,” they will at some point be decided by a federal court in the context of an actual patent case, with review in the Federal Circuit. If the question arises frequently, it will soon be resolved within the federal system, laying to rest any contrary state court precedent; if it does not arise frequently, it is unlikely to implicate substantial federal interests. […]

Minton also suggests that state courts’ answers to hypothetical patent questions can sometimes have real-world effect on other patents through issue preclusion. […] He argues that, in evaluating [a related patent] application [he filed], the patent examiner could be bound by the Texas trial court’s interpretation of the scope of Minton’s original patent. It is unclear whether this is true. […] In fact, Minton has not identified any case finding such preclusive effect based on a state court decision. But even assuming that a state court’s case-within-a-case adjudication may be preclusive under some circumstances, the result would be limited to the parties and patents that had been before the state court. Such “fact-bound and situation-specific” effects are not sufficient to establish federal arising under jurisdiction.

Nor can we accept the suggestion that the federal courts’ greater familiarity with patent law means that legal malpractice cases like this one belong in federal court. […][T]he possibility that a state court will incorrectly resolve a state claim is not, by itself, enough to trigger the federal courts’ exclusive patent jurisdiction, even if the potential error finds its root in a misunderstanding of patent law.

There is no doubt that resolution of a patent issue in the context of a state legal malpractice action can be vitally important to the particular parties in that case. But something more, demonstrating that the question is significant to the federal system as a whole, is needed. That is missing here.

D

It follows from the foregoing that Grable’s fourth requirement is also not met. That requirement is concerned with the appropriate “balance of federal and state judicial responsibilities.” We have already explained the absence of a substantial federal issue within the meaning of Grable. The States, on the other hand, have “a special responsibility for maintaining standards among members of the licensed professions.” […] We have no reason to suppose that Congress—in establishing exclusive federal jurisdiction over patent cases—meant to bar from state courts state legal malpractice claims simply because they require resolution of a hypothetical patent issue. […]

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Texas is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

12.2 Diversity of Citizenship

Article III extends the subject-matter jurisdiction of federal courts to “controversies … between citizens of different states.” Why do you think the framers of Article III might have given that class of cases to federal as opposed to state courts? What might their concerns have been? These questions are especially pressing given that diversity jurisdiction was quite controversial, and provided one of the main points of attack for skeptics of the new federal constitution during the ratification debates.

Recall that subject-matter jurisdiction requires both constitutional and statutory authorization. Just as Osborn set the constitutional test for federal-question jurisdiction, the next case distinguishes between the statutory and constitutional tests for subject-matter jurisdiction based on diversity of citizenship. And as with federal-question jurisdiction, the constitutional test for diversity jurisdiction is much more expansive than the statutory test, despite nearly identical text.

Strawbridge v. Curtiss

MARSHALL, Ch. J. delivered the opinion of the court.

The court has considered this case, and is of opinion that the jurisdiction cannot be supported.

The words of the act of congress are, “where an alien is a party; or the suit is between a citizen of a state where the suit is brought, and a citizen of another state.”

The court understands these expressions to mean that each distinct interest should be represented by persons, all of whom are entitled to sue, or may be sued, in the federal courts. That is, that where the interest is joint, each of the persons concerned in that interest must be competent to sue, or liable to be sued, in those courts.

But the court does not mean to give an opinion in the case where several parties represent several distinct interests, and some of those parties are, and others are not, competent to sue, or liable to be sued, in the courts of the United States.

[…]

Notes & Questions

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution extends the judicial power to all cases “between citizens of different states.” Courts have interpreted this language to require “minimal diversity,” meaning that the state citizenship of at least one plaintiff and defendant must be different. By contrast, courts have interpreted Strawbridge v. Curtiss as requiring “complete diversity,” meaning that every plaintiff must be a citizen of a different state from every defendant.

In a later case, the Supreme Court claimed that Chief Justice Marshall regretted how Strawbridge came to be understood:

By no one was the correctness of [Strawbridge] more questioned than by the late chief justice who [wrote it]. It is within the knowledge of several of us, that he repeatedly expressed regret [about the decision in Strawbridge], adding, whenever the subject was mentioned, that if the point of jurisdiction was an original one, the conclusion would be different.

Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston R.R. Co. v. Letson, 43 U.S. 497, 555 (1844).

- James Madison, an advocate for diversity jurisdiction’s inclusion in Article III, defended it only weakly at the Constitutional Convention:

As to its cognizance of disputes between citizens of different states, I will not say it is a matter of such importance. Perhaps it might be left to the state courts. But I sincerely believe this provision will be rather salutary, than otherwise. It may happen that a strong prejudice may arise in some states, against the citizens of others, who may have claims against them. We know what tardy, and even defective administration of justice, has happened in some states. A citizen of another state might not chance to get justice in a state court, and at all events he might think himself injured.

3 Elliot, Debates on the Federal Constitution 391 (1828). Subsequent commentators are skeptical of Madison’s justifications. See, e.g., Henry J. Friendly, The Historic Basis of Diversity Jurisdiction, 41 Harv. L. Rev. 483, 492–97 (1928). As you read the cases that follow, see whether you think that diversity jurisdiction is necessary, salutary, and effective at achieving its stated goals.

Mas v. Perry

AINSWORTH, Circuit Judge:

[…] Appellees Jean Paul Mas, a citizen of France, and Judy Mas were married at her home in Jackson, Mississippi. Prior to their marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Mas were graduate assistants, pursuing coursework as well as performing teaching duties, for approximately nine months and one year, respectively, at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Shortly after their marriage, they returned to Baton Rouge to resume their duties as graduate assistants at LSU. They remained in Baton Rouge for approximately two more years, after which they moved to Park Ridge, Illinois. At the time of the trial in this case, it was their intention to return to Baton Rouge while Mr. Mas finished his studies for [a PhD]. Mr. and Mrs. Mas were undecided as to where they would reside after that.

Upon their return to Baton Rouge after their marriage, appellees rented an apartment from appellant Oliver H. Perry, a citizen of Louisiana. This appeal arises from a final judgment entered on a jury verdict awarding $5,000 to Mr. Mas and $15,000 to Mrs. Mas for damages incurred by them as a result of the discovery that their bedroom and bathroom contained “two-way” mirrors and that they had been watched through them by the appellant during three of the first four months of their marriage.

At the close of the appellees’ case at trial, appellant made an oral motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. The motion was denied by the district court. Before this Court, appellant challenges the final judgment below solely on jurisdictional grounds, contending that appellees failed to prove diversity of citizenship among the parties and that the requisite jurisdictional amount is lacking with respect to Mr. Mas. Finding no merit to these contentions, we affirm. Under section 1332(a)(2), the federal judicial power extends to the claim of Mr. Mas, a citizen of France, against the appellant, a citizen of Louisiana. Since we conclude that Mrs. Mas is a citizen of Mississippi for diversity purposes, the district court also properly had jurisdiction under section 1332(a)(1) of her claim.

It has long been the general rule that complete diversity of parties is required in order that diversity jurisdiction obtain; that is, no party on one side may be a citizen of the same State as any party on the other side. Strawbridge v. Curtiss. This determination of one’s State citizenship for diversity purposes is controlled by federal law, not by the law of any State. As is the case in other areas of federal jurisdiction, the diverse citizenship among adverse parties must be present at the time the complaint is filed. The burden of pleading the diverse citizenship is upon the party invoking federal jurisdiction, and if the diversity jurisdiction is properly challenged, that party also bears the burden of proof.

To be a citizen of a State within the meaning of section 1332, a natural person must be both a citizen of the United States and a domiciliary of that State. For diversity purposes, citizenship means domicile; mere residence in the State is not sufficient.

A person’s domicile is the place of “his true, fixed, permanent home and principal establishment, and to which he has the intention of returning whenever he is absent therefrom.” A change of domicile may be effected only by a combination of two elements: (a) taking up residence in a different domicile with (b) the intention to remain there.

It is clear that at the time of her marriage, Mrs. Mas was a domiciliary of the State of Mississippi. While it is generally the case that the domicile of the wife—and, consequently, her State citizenship for purposes of diversity jurisdiction—is deemed to be that of her husband, we find no precedent for extending this concept to the situation here, in which the husband is a citizen of a foreign state but resides in the United States. Indeed, such a fiction would work absurd results on the facts before us. If Mr. Mas were considered a domiciliary of France—as he would be since he had lived in Louisiana as a student-teaching assistant prior to filing this suit, then Mrs. Mas would also be deemed a domiciliary, and thus, fictionally at least, a citizen of France. She would not be a citizen of any State and could not sue in a federal court on that basis; nor could she invoke the alienage jurisdiction to bring her claim in federal court, since she is not an alien. On the other hand, if Mrs. Mas’s domicile were Louisiana, she would become a Louisiana citizen for diversity purposes and could not bring suit with her husband against appellant, also a Louisiana citizen, on the basis of diversity jurisdiction. These are curious results under a rule arising from the theoretical identity of person and interest of the married couple.

An American woman is not deemed to have lost her United States citizenship solely by reason of her marriage to an alien. 8 U.S.C. § 1489. Similarly, we conclude that for diversity purposes a woman does not have her domicile or State citizenship changed solely by reason of her marriage to an alien.

Mrs. Mas’s Mississippi domicile was disturbed neither by her year in Louisiana prior to her marriage nor as a result of the time she and her husband spent at LSU after their marriage, since for both periods she was a graduate assistant at LSU. Though she testified that after her marriage she had no intention of returning to her parents’ home in Mississippi, Mrs. Mas did not effect a change of domicile since she and Mr. Mas were in Louisiana only as students and lacked the requisite intention to remain there. Until she acquires a new domicile, she remains a domiciliary, and thus a citizen, of Mississippi.

[The court’s analysis of the amount-in-controversy requirement is omitted.]

Thus the power of the federal district court to entertain the claims of appellees in this case stands on two separate legs of diversity jurisdiction: a claim by an alien against a State citizen; and an action between citizens of different States. We also note, however, the propriety of having the federal district court entertain a spouse’s action against a defendant, where the district court already has jurisdiction over a claim, arising from the same transaction, by the other spouse against the same defendant. In the case before us, such a result is particularly desirable. The claims of Mr. and Mrs. Mas arise from the same operative facts, and there was almost complete interdependence between their claims with respect to the proof required and the issues raised at trial. Thus, since the district court had jurisdiction of Mr. Mas’s action, sound judicial administration militates strongly in favor of federal jurisdiction of Mrs. Mas’s claim.

Affirmed.

Notes & Questions

The Mas case concerns not only diversity jurisdiction but also its cousin, alienage jurisdiction, which exists in a suit between a citizen and an alien (rather than a suit between citizens of different states).

Note that 28 U.S.C. § 1332, the diversity-jurisdiction statute, requires not only complete diversity but also that the amount in controversy exceed a specified dollar amount. Though Congress has increased that amount over the years to account for inflation, today the requirement is that the amount in controversy exceed $75,000. Typically the amount in controversy is determined by looking at the plaintiff’s complaint, and it does not require any assessment of how likely the plaintiff is to prevail or to persuade a jury that her damages are as much as she alleges. Nevertheless, questions frequently arise about how to value non-monetary forms of relief like injunctions. At least three approaches exist for such valuations: 1. the cost to the defendant of complying; 2. the benefit to the plaintiff of defendant’s compliance; or 3. some combination of both. Courts have divided on which is the right approach.

Mas turns heavily on the concept of domicile. A person is a citizen of state if they are domiciled there. What is the test for determining a person’s domicile? What does it take for a person to establish a new domicile?

Where is a corporation domiciled for purposes of diversity jurisdiction? The test applied in Mas seems like a poor fit for a corporation. So what test should apply? The Supreme Court answered that question in the next case.

Hertz Corp. v. Friend

BREYER, J., delivered the unanimous opinion of the court.

The federal diversity jurisdiction statute provides that “a corporation shall be deemed to be a citizen of any State by which it has been incorporated and of the State where it has its principal place of business.” 28 U.S.C. §1332(c)(1) (emphasis added). We seek here to resolve different interpretations that the Circuits have given this phrase. In doing so, we place primary weight upon the need for judicial administration of a jurisdictional statute to remain as simple as possible. And we conclude that the phrase “principal place of business” refers to the place where the corporation’s high level officers direct, control, and coordinate the corporation’s activities. Lower federal courts have often metaphorically called that place the corporation’s “nerve center.” We believe that the “nerve center” will typically be found at a corporation’s headquarters.

[…]

[The case grew from a class action. Hertz employees in California alleged that Hertz had failed to conform to California’s wage and hour laws. Hertz sought to remove to federal court, invoking diversity jurisdiction. The employees resisted with the argument that California was a principal place of business for Hertz, since it derived more revenue from that state than any other and the plurality of its business activities also occurred there. Reasoning that, because of this business activity Hertz was, like them, a citizen of California, the plaintiffs resisted removal. The District Court found that Hertz was a citizen of California, relying on Ninth Circuit precedent instructing “courts to identify a corporation’s ‘principal place of business’ by first determining the amount of a corporation’s business activity State by State. If the amount of activity is ‘significantly larger’ or ‘substantially predominates’ in one State, then that State is the corporation’s ‘principal place of business.’” The Ninth Circuit affirmed. The Supreme Court reviewed the history of “principal place of business” and its judicial interpretations.]

V

A

In an effort to find a single, more uniform interpretation of the statutory phrase, we have reviewed the Courts of Appeals’ divergent and increasingly complex interpretations. Having done so, we now return to, and expand, Judge Weinfeld’s approach, as applied [in a case decided shortly after the 1958 amendment to §1332 created dual corporate citizenship]. We conclude that “principal place of business” is best read as referring to the place where a corporation’s officers direct, control, and coordinate the corporation’s activities. It is the place that Courts of Appeals have called the corporation’s “nerve center.” And in practice it should normally be the place where the corporation maintains its headquarters—provided that the headquarters is the actual center of direction, control, and coordination, i.e., the “nerve center,” and not simply an office where the corporation holds its board meetings (for example, attended by directors and officers who have traveled there for the occasion).

Three sets of considerations, taken together, convince us that this approach, while imperfect, is superior to other possibilities. First, the statute’s language supports the approach. The statute’s text deems a corporation a citizen of the “State where it has its principal place of business.” 28 U.S.C. § 1332(c)(1). The word “place” is in the singular, not the plural. The word “principal” requires us to pick out the “main, prominent” or “leading” place. 12 Oxford English Dictionary 495 (2d ed. 1989) (def.(A)(I)(2)). And the fact that the word “place” follows the words “State where” means that the “place” is a place within a State. It is not the State itself.

A corporation’s “nerve center,” usually its main headquarters, is a single place. The public often (though not always) considers it the corporation’s main place of business. And it is a place within a State. By contrast, the application of a more general business activities test has led some courts, as in the present case, to look, not at a particular place within a State, but incorrectly at the State itself, measuring the total amount of business activities that the corporation conducts there and determining whether they are “significantly larger” than in the next-ranking State.

[…]

Second, administrative simplicity is a major virtue in a jurisdictional statute. Complex jurisdictional tests complicate a case, eating up time and money as the parties litigate, not the merits of their claims, but which court is the right court to decide those claims. Complex tests produce appeals and reversals, encourage gamesmanship, and, again, diminish the likelihood that results and settlements will reflect a claim’s legal and factual merits. Judicial resources too are at stake. Courts have an independent obligation to determine whether subject-matter jurisdiction exists, even when no party challenges it. So courts benefit from straightforward rules under which they can readily assure themselves of their power to hear a case.

Simple jurisdictional rules also promote greater predictability. Predictability is valuable to corporations making business and investment decisions. Predictability also benefits plaintiffs deciding whether to file suit in a state or federal court.

A “nerve center” approach, which ordinarily equates that “center” with a corporation’s headquarters, is simple to apply comparatively speaking. The metaphor of a corporate “brain,” while not precise, suggests a single location. By contrast, a corporation’s general business activities more often lack a single principal place where they take place. That is to say, the corporation may have several plants, many sales locations, and employees located in many different places. If so, it will not be as easy to determine which of these different business locales is the “principal” or most important “place.”

Third, the statute’s legislative history, for those who accept it, offers a simplicity-related interpretive benchmark. The Judicial Conference provided an initial version of its proposal that suggested a numerical test. A corporation would be deemed a citizen of the State that accounted for more than half of its gross income. The Conference changed its mind in light of criticism that such a test would prove too complex and impractical to apply. That history suggests that the words “principal place of business” should be interpreted to be no more complex than the initial “half of gross income” test. A “nerve center” test offers such a possibility. A general business activities test does not.

B

We recognize that there may be no perfect test that satisfies all administrative and purposive criteria. We recognize as well that, under the “nerve center” test we adopt today, there will be hard cases. For example, in this era of telecommuting, some corporations may divide their command and coordinating functions among officers who work at several different locations, perhaps communicating over the Internet. That said, our test nonetheless points courts in a single direction, towards the center of overall direction, control, and coordination. Courts do not have to try to weigh corporate functions, assets, or revenues different in kind, one from the other. Our approach provides a sensible test that is relatively easier to apply, not a test that will, in all instances, automatically generate a result.

We also recognize that the use of a “nerve center” test may in some cases produce results that seem to cut against the basic rationale for 28 U.S.C. §1332. For example, if the bulk of a company’s business activities visible to the public take place in New Jersey, while its top officers direct those activities just across the river in New York, the “principal place of business” is New York. One could argue that members of the public in New Jersey would be less likely to be prejudiced against the corporation than persons in New York—yet the corporation will still be entitled to remove a New Jersey state case to federal court. And note too that the same corporation would be unable to remove a New York state case to federal court, despite the New York public’s presumed prejudice against the corporation.